AS A YOUNG BOY in the 1930s, my father attended public school in Snina, a town in eastern Czechoslovakia. Twice a week, a Catholic priest would come in to teach the catechism, during which the few children who were Jewish were sent to wait outside. As they left the classroom, my father recalls, the priest invariably made some insulting remark about the Jewish people.

For Jews in the Europe of my father's youth, such Christian contempt was a fact of life. Its origins lay in the church's ancient claim that God had rejected the Jews when they rejected Jesus and that His covenant with Israel had been superseded by a new covenant with a "new Israel" -- namely, the Christian church. This 'teaching of contempt' fed an often virulent anti-Semitism, which created the climate for Europe's long history of persecuting Jews. Sixty-five years ago that history culminated in the Holocaust.

Yet not every priest in that era treated Jews with disdain.

Consider the story of Moses and Helen Hiller, a Jewish couple in Nazi-occupied Poland who entrusted their 2-year-old son to a Catholic family named Jachowicz in November of 1942. The Hillers begged their friends to keep their child safe -- and, should they not survive, to send him to family members abroad who would bring him up as a Jew. Soon after, the Hillers were deported to Auschwitz. They never returned.

The Jachowiczes came to love the little boy as their own and decided, when the war was over, to adopt him. Mrs. Jachowicz asked a young priest in Krakow to baptize the child, explaining that he had been born Jewish and that his parents had died. But when the priest, some of whose friends had also died in Auschwitz, learned of the Hillers' wish that their son not be lost to the Jewish people, he refused to perform the baptism. Instead he insisted that the Jachowiczes contact the child's relatives.

Today that boy is a middle-aged man, an observant Jew with children of his own. The young priest, whose name was Karol Wojtyla, died last week. He will be buried on Friday as Pope John Paul II, in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

When it came to the Jews, John Paul's attitudes were revolutionary. He had grown up with Jews as neighbors and classmates; he and his father rented the second floor of a house whose Jewish owners lived below. At a time when the Polish church could be vilely anti-Semitic -- in 1936 the Catholic primate of Poland, Cardinal Augustus Hlond, issued a pastoral letter declaring that "there will be a Jewish problem as long as Jews remain" and painting Jews as corrupters and atheists guilty of "spreading pornography" and "perpetrating fraud, practicing usury, and dealing in prostitution" -- the future pope's closest friend was a Jewish boy, Jerzy Kluger. To the young Father Wojtyla, the contempt for Jews and Judaism that came so readily to priests like the one in my father's school must have always rung false, even heretical.

And so he fought it. As a priest in Krakow, he would not countenance the betrayal of murdered Jewish parents by baptizing their child. As a young bishop at the Second Vatican Council, he spoke up powerfully in support of Nostra Aetate, the landmark Vatican declaration that renounced the idea of Jewish guilt for the death of Jesus and affirmed that God's covenant with the Jews is unbroken.

In 1979, on his first papal visit back to Poland, John Paul journeyed to Auschwitz, taking pains to emphasize what the communist government of that era took pains to obscure: the Jewish identity of the Holocaust. He paused deliberately before a memorial plaque written in Hebrew -- one of many plaques in many languages that the communists had installed. "This inscription awakens the memory of people whose sons and daughters were destined for total extermination," he said. "The very people that received from God the commandment 'Thou shall not kill' itself experienced in a special measure what is meant by killing."

"It is not permissible," he continued, "for anyone to pass by this inscription with indifference."

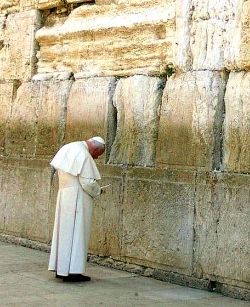

At the Western Wall in Jerusalem in March 2000, Pope John Paul II prayed for "genuine brotherhood" between Christians and Jews, "the people of the Covenant." |

Milestone followed milestone. In 1986 John Paul paid the first papal visit to the Great Synagogue in Rome, where he stressed the debt that Christians owe to the Jews, "our elder brothers." In 1993, he formally recognized the state of Israel, repudiating forever the old theology that Jews were doomed to everlasting exile, never again to be sovereign in their homeland. He became the first pope to publicly beg forgiveness for Christian wrongs done to the Jewish people.

And in 2000, on a deeply emotional pilgrimage to the Holy Land, he became the first pope to pray at the Western Wall, a moment of reverence for the Jewish faith -- and for the Temple that was once its beating heart -- that would have been unthinkable for most of the preceding two millennia.

If John XXIII was the "good pope" who set in motion the great shift in the church's relations with the Jewish people, John Paul II was the great pope who made it undeniable and irrevocable. As he is laid to his rest, Jews and Christians will shed tears together.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his weekly email newsletter.