THE ARCHBISHOP of Buenos Aires became the supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church when he pronounced the word "accepto" – Latin for "I accept" – in the Sistine Chapel last week. From that moment, according to Catholic theology, Pope Francis had "full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church." Most notably, he was endowed with what the catechism calls "the charism of infallibility": When the pope, in his role as the church's supreme pastor and teacher, definitively proclaims "a doctrine pertaining to faith or morals," he is incapable of error.

The dogma of papal infallibility, approved at the First Vatican Council in 1870, was fiercely challenged by Lord Acton, the celebrated English historian and champion of liberty. Though a devout lifelong Roman Catholic, Acton fervently opposed papal absolutism – so fervently that he traveled to Rome to organize a campaign against the infallibility doctrine, which he was convinced would be used to justify wrongdoing and suppress freedom of conscience. "The theory of infallibility ... stands on a basis of fraud," he wrote.

Acton failed – Vatican I voted overwhelmingly to promulgate the doctrine – but his conviction never wavered. "There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it," he later wrote to the Anglican cleric Mandell Creighton. It was in the same letter that Acton expressed his most famous warning: "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely."

Though I'm not a Christian, I followed news of the papal conclave with great interest and am impressed by its outcome. By all accounts, the new pope seems a humble, kind, thoughtful man. Perhaps he will even prove a saintly one, in the manner of Francis of Assisi, from whom he takes his pontifical name.

But infallible? As an observant Jew, I come from a religious tradition that has always expressed a very different view of religious leadership and authority. In normative Judaism, not even the greatest leader, the wisest sage, or the most renowned rabbi is infallible. The Great Sanhedrin of Jerusalem was the supreme legal and religious authority in ancient Israel; its 71 justices were required to be men of humility, integrity, and compassion, known as much for their scholarship in religious matters as for their wide-ranging knowledge of science, mathematics, and languages. Their credentials were stellar, and their rulings were final.

Yet not even they were incapable of error – not even when definitively proclaiming what Vatican I might have called "a doctrine pertaining to faith or morals." The Bible itself anticipates that the entire nation might be led to sin because the Sanhedrin got something wrong: because the truth was "hidden from the eyes of the assembly," as Leviticus puts it, and the judges didn't realize their error until it was too late. In fact, the Talmud devotes an entire volume to the subject of erroneous rulings by the highest religious authorities.

Like all faiths, Judaism has its share of zealots and rigid fundamentalists. And there are certainly charismatic rabbis with passionately devoted followers who seek their advice in every area of life and treat it, you should pardon the expression, as gospel truth. But even among the most traditionally observant, there has never been a Jewish equivalent to the pope, or to the Catholic teaching that doctrinal infallibility comes with the office.

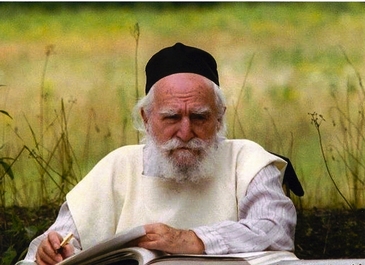

Rabbi Moshe Feinstein: "You can't wake up in the morning and decide you're an expert." |

In 1975, the New York Times interviewed the late Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, an illustrious scholar who was widely regarded as the foremost living authority on Jewish law. Fielding thousands of queries from around the world, ruling on many of the thorniest controversies in Jewish life, "he is the closest that Orthodox Jewry comes to a court of last resort," the Times wrote. But it was not "by appointment or election" that he had achieved his extraordinary jurisprudential influence. It was through trust.

"You can't wake up in the morning and decide you're an expert on answers," he said. "If people see that one answer is good, and another answer is good, gradually you will be accepted." In this system it is not the shepherd's "accepto" that matters. It is the flock's.

Pope Francis is described by those who know him as modest and self-effacing, committed to a church "that does not so much regulate the faith as promote and facilitate it." You don't have to be Catholic to pray that the cardinals have chosen well, and that the 266th pope will lead with wisdom, honesty, grace, and an understanding heart. Ultimately it is those qualities, not "infallibility," on which the success of his papacy depend.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter