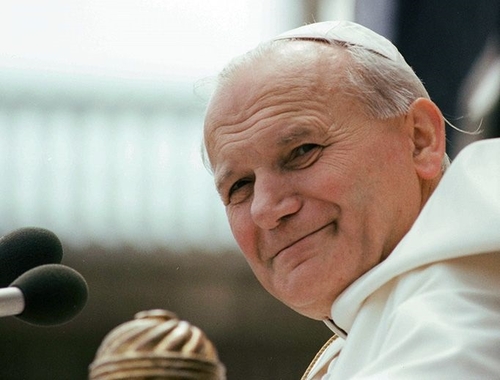

JOHN PAUL II, the most charismatic and consequential pope in modern times, is associated in my mind with two Jewish holidays.

I first learned of him on Oct. 16, 1978, the day he was elected by the conclave of cardinals gathered in the Sistine Chapel. It was the first day of Sukkot, the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles, and I was walking to my synagogue in Washington, D.C., for evening services. A newspaper headline — it must have been in the old Washington Star, an afternoon paper — jumped out at me from a vending box on Pennsylvania Avenue: "Habemus Papam!" The Latin phrase means "We have a pope," and is the traditional announcement made by the senior cardinal in the conclave upon the election of a pontiff.

At the time, I didn't know anything about the new Polish pope. A year later, I knew much more, since I had followed with interest the coverage of his trip back home to Poland in June 1979. Already it was becoming clear that John Paul II was no ordinary pope. So when it was announced that he would travel to the United States in the fall, beginning with a stop in Boston (where I had recently relocated to attend law school), I decided to go and see him when he appeared on Boston Common. But it wasn't to be: The pope's visit to Boston coincided with Yom Kippur, the most solemn day of the Jewish year. Instead of heading into town to see the leader of the Catholic Church, I spent the day in the synagogue, fasting and in prayer.

The future pope, born 100 years ago today as Karol Wojtyla in the Polish town of Wadowice, initially had no interest in becoming a priest. It was the theater that fascinated him; in his teens, he was "obsessed" (his word) with acting and the stage. When he became a university student at 18, he later said, a vocation in the priesthood was the furthest thing from his mind. That changed during World War II. Amid the Nazi occupation of Poland, Wotyla found his calling in the church. By the time he was ordained in 1946, Poland was under communist rule, with a government hostile to religion. The new priest began quickly to be noticed — first as a brilliant intellectual, then as an increasingly outspoken champion of human rights. By 1958 he had been made a bishop; in 1967, he was named to the College of Cardinals by Pope Paul VI. Eleven years later, the 58-year-old Wojtyla became pope himself — the first non-Italian to ascend the throne of St. Peter in 450 years, and the first Slavic pope in history.

Yet that was the least of his historic achievements. When John Paul II died in 2005, Henry Kissinger — himself a figure of considerable historic significance — said that it would be hard to think of anyone whose impact on the 20th century had been more profound. The pope left his mark in numerous ways, but two in particular stand out in my mind.

One was his pivotal role in the downfall of Communism in Poland, the collapse of the Iron Curtain, and the disappearance of the Soviet Union. Without John Paul II, America and the West might never have won the Cold War. Testimony to that effect came from none other than Mikhail Gorbachev, the last general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. "Everything that happened in Eastern Europe in these last few years," he wrote in 1992, "would have been impossible without the presence of this pope."

It began with that trip to Poland in 1979, the first of nine journeys John Paul would make to his homeland during his 27-year papacy.

Documents later unearthed in the Kremlin archives show that communist rulers expected the new pope to adopt "a new aggressiveness" toward the Soviet bloc. "Wojtyla will apparently be less willing to compromise with the leadership of the socialist states," forecast a report prepared for the Central Committee in Moscow shortly after John Paul's investiture. When he sought permission to visit Poland in 1979, then-Soviet ruler Leonid Brezhnev recommended that he be turned down. But Polish officials felt they had no choice but to welcome the first Polish pope, despite their misgivings.

A secret memorandum sent by the Communist Party to teachers in the nation's schools in advance of John Paul's arrival expressed those misgivings with panicky clarity:

The Pope is our enemy. . . . Due to his uncommon skills and great sense of humor he is dangerous, because he charms everyone, especially journalists. Besides, he goes for cheap gestures in his relations with the crowd; for instance, [he] puts on a highlander's hat, shakes all hands, kisses children, etc. . . . It is modeled on American presidential campaigns. . . . Because of the activities of the Church in Poland, our activities designed to atheize the youth not only cannot diminish but must intensely develop.

But the message from the pope, delivered in one Polish city after another to crowds numbering in the hundreds of thousands, proved irresistible. "Be not afraid," he repeated again and again. "Never despair, never grow weary, never become discouraged."

The impact of those words on Poland's people was powerful. After decades under numbing, despondency-inducing totalitarian rule, Poles began to see a different possibility for themselves. "Suddenly cognizant of their own history, their own heritage, they wondered why they had allowed themselves to be frightened for so long," wrote Joseph Shattan in his 1999 book on the Cold War's "architects of victory."

In the wake of the pope's galvanizing visit, it grew increasingly clear that the status quo could not last. In July 1980, the Polish government decreed a sharp increase in food prices, prompting tens of thousands of workers nationwide to go on strike, and to organize an independent trade union, Solidarity, led by an electrician at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk named Lech Walesa.

"The most remarkable feature of the strikes that led to the formation of Solidarity was their religious, nonviolent character," Shattan recounted.

In contrast to earlier strike waves that had swept through Poland . . . workers in the summer of 1980 confined themselves to nonviolent sit-down strikes. The influence of the church and the pope were everywhere apparent, especially at the Gdansk shipyard. 'During their memorable strike in 1980,' Lech Walesa later wrote, 'the first things the Gdansk workers did was to affix a cross, an image of the Virgin Mary, and a portrait of John Paul II to the gates of the shipyards.' Walesa himself wore a pin with a picture of Poland's most revered icon, the Black Madonna of Czestochowa, in his lapel, and the oversized pen with which he signed the [strike-ending] August 31 Gdansk accords — a souvenir from John Paul II's trip to Poland — had the pope's picture on it.

The 1979 trip to Poland detonated a psychological and social explosion that became unstoppable. As Solidarity grew in strength, Moscow insisted with growing vehemence that the Polish government suppress its deepening influence. Warsaw Pact forces carried out military maneuvers along Poland's borders, but there was to be no repeat of 1956 and 1968, when the Kremlin ordered troops to invade Hungary and Czechoslovakia, respectively. In December 1981, martial law was imposed by the communist regime in Warsaw; Solidarity leaders, including Walesa, were rounded up and imprisoned. "The counterrevolution is now crushed," Brezhnev told the Politburo the following month.

But the "counterrevolution" was just getting started, and it had considerable help from the Polish pope. In 1983, John Paul paid his second visit to Poland. He made a particular point of requesting permission to visit Walesa, thereby bolstering the anticommunist opposition and Solidarity's central role in the resistance. Within weeks of the pope's visit, martial law had been lifted. The pro-democracy movement grew steadily stronger. The dictatorship weakened.

In September 1989, communist rule ended for good in Poland with the election of a democratic government headed by Tadeusz Mazowiecki. Within months, communist regimes in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and East Germany were gone as well. The pope took a victory lap. "The irresistible thirst for freedom broke down walls and opened doors," he said in January 1990, because "women, young people, and men have overcome their fear."

Over and over, he had urged his followers: "Be not afraid." That message, propelled by the pope's humane, benign, and ultimately realistic worldview, led to the liberation of half a continent. It was an extraordinary achievement, one that answered forever Stalin's cynical put-down. "The pope?" sneered the Soviet dictator in 1935. "How many divisions does he have?" Of military divisions, John Paul II had none at all. Yet in the end he deployed enough power to topple the mighty Soviet empire.

The other aspect of the Polish pope's legacy that stands out in my mind is how he transformed the Roman Catholic Church in its attitude toward Jews.

As a young boy in the 1930s, my father attended public school in Snina, a town in eastern Czechoslovakia. Twice a week, a Catholic priest would come in to teach the catechism, while the few children who were Jewish would wait outside. As they left the classroom, my father recalls, the priest invariably made some insulting remark about Jews.

For Jewish citizens in the Europe of my father's youth, such Christian contempt was a fact of life. Its origins lay in the church's ancient claim that God had rejected the Jews when they rejected Jesus. This "teaching of contempt" fed an often virulent antisemitism, which created the climate for Europe's long history of religious persecution. Eight decades ago, that history culminated in the Holocaust.

Yet as I wrote in 2005 after the death of John Paul II, not every priest in that era treated Jews with disdain:

Consider the story of Moses and Helen Hiller, a Jewish couple in Nazi-occupied Poland who entrusted their 2-year-old son to a Catholic family named Jachowicz in November of 1942. The Hillers begged their friends to keep their child safe — and, should they not survive, to send him to family members abroad who would bring him up as a Jew. Soon after, the Hillers were deported to Auschwitz. They never returned.

The Jachowiczes came to love the little boy as their own and decided, when the war was over, to adopt him. Mrs. Jachowicz asked a young priest in Krakow to baptize the child, explaining that he had been born Jewish and that his parents had died. But when the priest, some of whose friends had also died in Auschwitz, learned of the Hillers' wish that their son not be lost to the Jewish people, he refused to perform the baptism. Instead he insisted that the Jachowiczes contact the child's relatives.

Today that boy is a middle-aged man, an observant Jew with children of his own. The young priest, whose name was Karol Wojtyla, died last week. He will be buried on Friday as Pope John Paul II, in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

When it came to the Jews, John Paul's attitudes were revolutionary. He had grown up with Jews as neighbors and classmates. Roughly one-fourth of Wadowice's population was Jewish, and the young Karol Wojtyla was fond of his Jewish friends. He and his father lived on the upper floor of a house whose Jewish owners lived below. At a time when the Polish church could be vilely antisemitic — in 1936 the Catholic primate of Poland, Cardinal Augustus Hlond, issued a pastoral letter declaring that "there will be a Jewish problem as long as Jews remain" and painting Jews as corrupters , atheists, and pornographers — the future pope's closest companion was a Jewish boy, Jerzy Kluger. To the young Father Wojtyla, the contempt for Jews and Judaism that came so readily to priests like the one in my father's school or to Cardinal Hlond must have always rung false, even heretical.

So he fought it. As a priest in Krakow, he would not countenance the betrayal of murdered Jewish parents by baptizing their child. As a young bishop at the Second Vatican Council convened by Pope John XXIII, he supported Nostra Aetate, the landmark Vatican declaration repudiating the idea of Jewish guilt for deicide and affirming that God's covenant with the Jews is unbroken.

In 1979, on that first visit to Poland, John Paul went to Auschwitz, taking pains to emphasize what the communist government of that era took pains to obscure: the Jewish identity of the vast majority of the victims. He paused deliberately before a memorial plaque written in Hebrew — one of many plaques in many languages that the communists had installed. "This inscription awakens the memory of people whose sons and daughters were destined for total extermination," he said. "The very people that received from God the commandment 'Thou shall not kill' itself experienced a singular ordeal in killing."

"It is not permissible," he continued, "for anyone to pass by this inscription with indifference."

Milestone followed milestone. In 1986 John Paul paid the first papal visit to the Great Synagogue in Rome, where he stressed the debt that Christians owe to the Jews, "our elder brothers." In 1993, he formally recognized the state of Israel, repudiating forever the old theology that Jews were doomed to everlasting exile, never again to be sovereign in their homeland. He became the first pope to publicly beg forgiveness for Christian wrongs done to the Jewish people.

And in 2000, on a deeply emotional pilgrimage to the Holy Land, he became the first pope to pray at the Western Wall, a moment of reverence for the Jewish faith — and for the Temple that was once its beating heart — that would have been unthinkable for most of the preceding two millennia.

If John XXIII was the "good pope" who set in motion the great shift in the church's relations with the Jewish people, John Paul II was the great pope who made it undeniable and irrevocable. The pope from Poland, a land with a deeply rooted history of hostility to Jews, made it his goal to expunge antisemitism from the Church of Rome, proclaiming it a sin and a desecration of Christianity.

It wasn't only Catholics who grieved when John Paul died, or who have reason to remember him with gratitude and admiration on this centennial of his birth.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The enemies of Prop 209

In 1996, California voters approved Proposition 209, a ballot measure accurately named the California Civil Rights Initiative. By a 55% majority, they amended their state's constitution to put an end to state-sponsored discrimination on the basis of race or gender. Proposition 209 required California's government to get out of the business of quotas, preferences, and set-asides — to stop judging its citizens by the color of their skin, and focus instead on the content of their character, the level of their ability, and the merit of their claim.

The University of California's freshman class in 2019 was the most racially diverse ever, without recourse to quotas or preferences. |

I was following the story at the time, and was struck by the fact that the organizers of Proposition 209 were mostly political amateurs linked by a principled commitment to colorblindness. They shared the view of Thurgood Marshall, who was the NAACP's chief litigator during the battle against Jim Crow segregation, that "classifications and distinctions based on race or color have no moral or legal validity in our society."

The opponents of Proposition 209, on the other hand, included some of the savviest political operators in California, from then-San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown to the National Organization for Women. Well-heeled left-wing organizations, such as the Ford Foundation and the California Teachers Association, poured vast sums into defeating the proposed amendment. Opponents of the California Civil Rights Initiative were vicious in their denunciation of the measure. One Los Angeles city councilor compared it to Mein Kampf . A state senator smeared Prop 209's chief sponsor, a black businessman and University of California regent named Ward Connerly, in nakedly racist terms: "He's married to a white woman. He wants to be white. . . . He has no ethnic pride."

But Proposition 209 had one great advantage. It was written in language so clear and compelling that every voter in California could understand it: "The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting." Most Californians agreed with that injunction — equal opportunity for all, quotas for none — and added it to their state's constitution.

Now a group of California legislators want to repeal Prop 209. They have introduced legislation to once again make it legal for college admissions, government hiring, and public contracting to be governed by racial and gender quotas.

The repeal legislation, known as Assembly Constitutional Amendment 5 (ACA-5) , contains a lengthy preamble that paints a doleful portrait of life in California without racial quotas: "reduces the graduation rates of students of color . . . . a devastating impact on minority equal opportunity and access to California's publicly funded institutions of higher education . . . . diversity within public educational institutions has been stymied . . . . a decreased likelihood of ever earning a graduate degree, and long-run declines in average wages."

But Gail Heriot, a law professor at the University of San Diego and a member of the US Commission on Civil Rights, argues that Prop 209 "has been good for Californians — of all races," and that ACA-5's proponents are deliberately misstating the data. By eliminating racial preferences, she wrote in a RealClearPolitics column on Saturday, the 1996 Civil Rights Initiative did away with the pressure to admit minority students to competitive institutions their credentials hadn't prepared them for. As a result, "the number of underrepresented minority students at [the University of California at] Berkeley decreased significantly."

But those students didn't just disappear. Most were accepted at other campuses of the prestigious UC system — based on their own academic records rather than their skin color. On several UC campuses, their numbers increased. More important, their performance improved dramatically.

Data from UC-San Diego (one of the more elite UC campuses) illustrate what happened.

In the year immediately prior to Proposition 209's implementation, only one African American student in the entire freshman class was an honor student. Following implementation, a full 20% of African American freshmen were. That was higher than the rate for Asian Americans (16%) and extremely close to the rate for whites in the same year (22%). Even more impressive, the number of under-represented minority students in academic jeopardy collapsed.

A further debunking of ACA-5 comes from Wenyuan Wu of the Asian American Coalition for Education. Writing in the Orange County Register, she laid out just how effective Proposition 209 has been at boosting enrollment and graduation rates for underrepresented minorities.

In the University of California system, four-year graduation rates of underrepresented racial minorities rose from 31.3% during the 1995-97 period, preceding Prop 209, to 36.6% during 1998-2000, then to 43.3% during 2001-03. In 2014, underrepresented racial minorities' four-year graduation rate rose to a record high of 55.1%. The six-year graduation rate has fared even better: 66.5% in 1998 and 75.1% in 2013.

What is true of minority graduation rates is equally true of minority admissions.

Minority admissions at UC exceed those of 1996 both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of all admissions.

Latino admissions went from 15.4% (5,744 students) in 1996 to 23% (14,081) in 2010; Asian-American admissions rose from 28.8% (11,085) to 37.47% (22,877), while black admissions from 4% (1,628) to 4.2% (2,624). In 1999, underrepresented racial minorities' enrollment at the UC system stood at a meager 15%, while in 2019 this figure increased to 26%. ACA-5's claim that "since the passage of Proposition 209, diversity within public educational institutions has been stymied" is simply untrue.

Last summer, the University of California system admitted the largest and most diverse class of freshmen in its history — without resorting to quotas. Fully 40% of the new undergraduates, reported the Los Angeles Times, were from "underrepresented" racial and ethnic groups; white students accounted for just 22% of the freshman class.

The enemies of Proposition 209 have tried several times to get it overturned by friendly courts, but were repeatedly shot down. The California Supreme Court twice upheld the ban on racial preferences, overturning municipal ordinances that attempted to establish race- and gender-based preferences in government contracting. In 2012, the Ninth Circuit US Court of Appeals, generally regarded as the most liberal of the federal appellate courts, upheld Proposition 209 as well.

California paved the way for the adoption of similar colorblind mandates in Michigan, Nebraska, Washington, and Arizona. Other states should follow suit. The Golden State is is often pointed to as an example of social looniness gone amok, but enshrining the California Civil Rights Initiative in the California constitution was an example of the opposite: In the nation's most multiracial, multiethnic state, voters 24 years ago pulled the plug on race- and sex-based affirmative action, one of the great wrong turns of American social policy. In doing so, they brought nearer the day when government no longer prefers some of its citizens over others because of their physical characteristics. ACA-5 would undo that noble achievement. Californians had better make sure that doesn't happen.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

GE: "We're No. 7!"

Stock in General Electric dropped to a new low last week, sinking at week's end to $5.49 a share. In nominal dollars, that's about what it was worth 30 years ago (much less, of course, if adjusted for inflation). And it is just a small fraction of the nearly $30 a share it was going for in January 2016, when Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker and Boston Mayor Marty Walsh were patting themselves on the backs — to the lusty cheers of many in the media — for having coaxed GE to shift its headquarters from Fairfield, Conn., to Boston's Fort Point Channel district.

At the time GE's move to Boston was announced, its market capitalization (the standard measure of the value of a publicly traded company) was about $270 billion. That instantly qualified GE as the most valuable company in Massachusetts. It debuted on the Globe 25 Index — a listing of the 25 biggest companies headquartered in Massachusetts — at No. 1, and by a wide margin.

And there it perched, high above its peers. Until, like Humpty Dumpty, it had a great fall.

GE is no longer the biggest fish in the Massachusetts corporate sea. It isn't the second-biggest. It isn't the third-, fourth-, fifth-, or sixth-biggest. Its market cap on Friday was $49.9 billion, putting it at No. 7, narrowly edging Boston Scientific Corp., which was in the No. 8 spot with a market value of $49.7 billion.

To be sure, many businesses are hurting now amid the COVID-19 pandemic, but GE's fall from its Olympian heights began long before anyone had heard of coronavirus. Baker and Walsh were tickled with themselves when they succeeded in luring GE to Boston with a package of taxpayer-funded incentives worth as much as $150 million in subsidies, abatements, training funds, site improvements, and property acquisition costs. "We won Powerball today," Walsh exulted at the time, while Baker serenely gave his assurance that doling out those rich bribes — er, incentives — to GE would prove to be "a good investment for Massachusetts and . . . Boston."

They wouldn't have said those things had they known how hard and fast GE was about to fall. Nor, I presume, would they have been willing to gamble taxpayers' money on a company that would prove unable to keep its pledge to put up a new headquarters building and hire hundreds of new employees. Needless to say, Baker and Walsh didn't know that GE was about to plunge down a hole and lose four-fifths of its value. Government officials never know what the future will bring for the companies they spend so lavishly to lure to their states and cities. Which is why those subsidies shouldn't exist in the first place. (To be fair, some of those financial inducements were tied to performance benchmarks; since GE didn't meet them, it didn't collect the benefits.)

"If subsidizing GE turns out to have been a losing bet," I wrote in 2017, when the company was already in trouble, "it will join a long roster of other losing bets. Massachusetts officials have repeatedly gambled with public dollars to entice companies to move to the state (or to keep local firms from leaving). They defend their wagers with happy talk of the jobs to be created or the cutting-edge industries to be established. Yet in case after case — Intel, Evergreen Solar, Nortel Networks, Fidelity Investments , Organogenesis — the promised jobs don't appear, or the company doesn't survive, or the forgone tax revenue is never made up."

A few years ago, the Pioneer Institute, a Boston think tank, crunched the data on the rich subsidies paid to the state's biotech industry, an initiative begun in 2009 under Governor Deval Patrick and continued under Baker. Of the 250,000 new jobs promised, Pioneer found, 95% never materialized. Between 2009 and 2016, as private-sector employment in Massachusetts grew by more than 15% (ah, those were the days!), the biotech sector — despite being nurtured with more than $650 million in government subsidies — grew by just 0.1%.

I wish nothing but success and prosperity to GE, its shareholders, its employees, and all who depend on it for their own welfare. I earnestly hope its fortunes turn around. But I also hope not another penny in government handouts goes to GE, or to any other private company.

The takeaway from General Electric's plunge from No. 1 to N0. 7 isn't that state and local governments should do more homework before they bet public funds on private companies they think will grow. It is that they shouldn't be making such bets in the first place. Governors, mayors, and legislators aren't smarter than the marketplace. They are no more infallible at picking commercial winners and losers. Pouring public funds into the coffers of favored private companies isn't economic development. It's crony capitalism, and a betrayal of the public trust.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The last line

"Our dead brothers still live for us, and bid us think of life, not death – of life to which in their youth they lent the passion and joy of the spring. As I listen, the great chorus of life and joy begins again, and amid the awful orchestra of seen and unseen powers and destinies of good and evil our trumpets sound once more a note of daring, hope, and will." — Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Memorial Day oration before Civil War veterans, Keene, N.H. (May 30, 1884)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter