IT WAS two years ago this week that John (Ivan) Demjanjuk flew back to Cleveland, Ohio. His return came 12 years after he had been stripped of his US citizenship for lying about his past as a Nazi collaborator; six years after he had been extradited to Israel to stand trial for murder; five years after he was convicted by an Israeli court of committing "cruel and torturous acts" in the Treblinka death camp; and two months after he was set free on a technicality by the Israeli Supreme Court.

Demjanjuk's presence in this country is obscene. He was an accessory to the most awful evil of the 20th century; the blood of unnumbered victims stains his hands. He entered America in the first place under false and illegal pretenses. His re-entry two Septembers ago was a travesty, one that only grows more rancid with the passage of time.

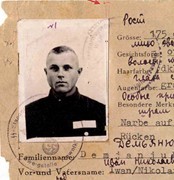

Demjanjuk's Nazi-issued ID card |

To this day, Demjanjuk's partisans protest that he was the victim; the real travesty, they say, was that a harmless man should have been put through such an ordeal. Pat Buchanan -- a ready defender of exposed Nazi criminals -- has labeled Demjanjuk a modern "Dreyfus" and compared him to the martyrs hanged by "the Salem judges."

A more deliberate perversion of history is hard to imagine. Dreyfus and the Salem "witches" were innocent, blamed for crimes they never committed. Demjanjuk's guilt, by contrast, is undeniable, and the evidence of his enormities overwhelming.

Like many other Ukrainians, Demjanjuk was glad to help the Nazis massacre Jews. In 1942, he volunteered to be a wachmann, a member of the extermination crews the Nazis set up in Poland and the Soviet Union. He was sent for training to the Trawniki concentration camp, where he took an oath of loyalty to the SS, and received its official tattoo. Like the other wachmanner trained at Trawniki, Demjanjuk mastered -- in the words of Israel's high court -- "every stage of the extermination process," from rounding up Jews in ghettoes to pumping carbon monoxide into gas chambers.

In Trawniki, Demjanjuk was issued ID card No.1393. The 5-by-7-inch ID, complete with photo and official stamps, still exists. It establishes beyond any whisper of doubt that Demjanjuk was a Nazi-trained accomplice to genocide. Though his lawyers loudly proclaimed the document a forgery, its authenticity was tested and confirmed by every court that heard the case.

On March 27, 1943, Demjanjuk was posted to the Sobibor death camp, one of three erected by the Germans to carry out "Operation Reinhard" -- the liquidation of the Jews of Poland and the eastern lands. Between March 1942 and October 1943, some 2,250,000 human beings were gassed to death in these camps. Most of the killing was committed by non-German collaborators, especially Lithuanians, Latvians -- and Ukrainians like Demjanjuk.

At some point in 1943, Demjanjuk was transferred to Treblinka. So infamous was his sadism there that he was nicknamed "Ivan Grozhny" -- Ivan the Terrible. Forty years later, survivors of Treblinka remembered him vividly. Seven Jewish eyewitnesses, some of them trembling and weeping, identified Demjanjuk as Ivan the Terrible, and testified in court to his brutalities. He would stab Jews as they were herded to the gas chambers; he would slice off noses and ears with a saber; he would cut women between their legs; he would lash victims with a whip.

"One day he ordered a prisoner to lie face down on the ground and . . . took a tool for drilling wood and drilled a hole into the prisoner's buttocks," a survivor testified. Another recalled: "Ivan split one head after another. I heard screams, crying. There were no words to describe it."

The eyewitnesses' words were transfixing. The evidence of Demjanjuk's crimes overwhelmed the defense. The Israeli Supreme Court found the testimony -- which was given under oath and subjected to cross-examination -- "effective corroboration," "reliable," and "convincing." What led the justices to vacate Demjanjuk's sentence was no weakness in the powerful and unimpeached evidence against him.

After the trial had ended, a batch of old depositions found in KGB files in Kiev -- statements made by long-dead guards at Treblinka -- suddenly materialized. No one knows who took these depositions, under what circumstances they were taken, or even what questions were asked. But in several of the statements a wachmann named Ivan Marchenko -- not Demjanjuk -- is mentioned as the gas chamber operator at Treblinka. Of course the statements might be false or mistaken. Or Marchenko and Demjanjuk might have been gas chamber operators at different times. Or the depositions could be phony.

"We do not know how these statements came into the world and who gave birth to them," the justices wrote. By normal standards of evidence, they should have been deemed worthless and inadmissible.

But unwilling to convict even a sadistic Nazi wachmann unless every detail of the case against him were perfect, the court let him go.

Justice miscarried. But there is no debating Demjanjuk's unspeakable past, and he has no business being on American soil. There is only one place where Demjanjuk belongs. He's 75; with any luck, he'll be there soon.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.