RIGHT ON THE HEELS of the recent news that Apple CEO Steve Jobs underwent a liver transplant came the speculation that he had somehow gamed the organ donation system in order to jump to the head of the waiting list. It was widely noted that Jobs's transplant took place at a hospital in Tennessee, some 2,000 miles from his home in California. That suggests he had registered with more than one regional transplant center. Multiple registrations aren't against the rules but they can be an expensive proposition, since the patient must be able to travel at a moment's notice when the organ becomes available, and since insurance companies generally won't pay for evaluations at more than one hospital. Jobs, a billionaire, may thus have benefited, frets USA Today, from "a loophole that favors the rich."

Had Jobs traveled to Tennessee to consult a highly sought-after medical specialist, or to acquire a piece of cutting-edge medical equipment, or to undergo a rare and difficult brain operation -- or to buy a Smoky Mountains mansion, for that matter -- nobody would be grumbling about loopholes or wondering whether rules had been manipulated. When it comes to doctors' services or medical technology or surgical procedures -- or real estate -- people understand that suppliers generally charge what the market will bear.

The same economic system that generally makes good health care available to all does price certain products and services high enough that only the wealthy can afford them. It isn't news that the world's finest surgeon commands a high fee, or that the latest "miracle" drugs tend to be expensive, or that billionaires can afford things that mere mortals can't.

Yet when it comes to the donation of human organs, countless people believe that the market must be prevented from functioning.

Under current law, an organ may be transplanted to save a patient's life only if it was donated for free. Federal law makes it "unlawful for any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation." The surgeon who performed Jobs's liver transplant, the hepatologist who diagnosed him, the anesthesiologist who managed his pain, the nurse who assisted during the procedure, the medical center that provided the facilities, the pharmacy that supplied his medications, even the driver who brought him to the hospital -- all of them were paid for the benefits they rendered. Only the organ donor (or the donor's family, if the liver came from a cadaver) could receive nothing except the satisfaction that comes from performing an act of kindness.

That, many say, is as it should be: Organs should be donated out of goodness alone; otherwise the rich might exploit the poor. Others flatly oppose any hint of commerce in human organs. Opening the door to "financial incentives," declared the Institute of Medicine in 2006, could "lead people to view organs as commodities and diminish donations from altruistic motives."

Unfortunately, altruistic motives aren't enough. I carry an organ donor card and think everyone should, but only 38 percent of licensed drivers have designated themselves as organ donors. Thousands of organs that could be used to save lives and restore health are lost each year, buried or cremated with bodies that will never need them again.

No one would dream of suggesting that medical care is too vital or sacred to be treated as a commodity, or to be bought and sold like any other service. If the law prohibited any "valuable consideration" for healing the sick, and allowed doctors to practice medicine only if they did so for free, the result would be far fewer doctors and far more sickness and death.

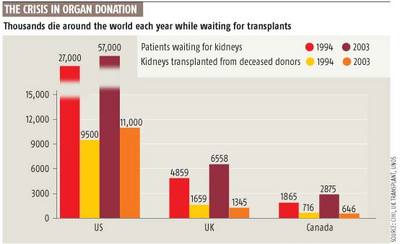

The result of our misguided altruism-only organ donation system is much the same: too few organs and too much death. More than 100,000 Americans are currently on the national organ waiting list. Last year, 28,000 transplants were performed, but 49,000 new patients were added to the queue. As the list grows longer, the wait grows deadlier, and the shortage of available organs grows more acute. Last year, 6,600 people died while awaiting the kidney or liver or heart that could have kept them alive. Another 18 people will die today. And another 18 tomorrow. And another 18 every day, until Congress fixes the law that causes so many valuable organs to be wasted, and so many lives to be needlessly lost.

The result of our misguided altruism-only organ donation system is much the same: too few organs and too much death. More than 100,000 Americans are currently on the national organ waiting list. Last year, 28,000 transplants were performed, but 49,000 new patients were added to the queue. As the list grows longer, the wait grows deadlier, and the shortage of available organs grows more acute. Last year, 6,600 people died while awaiting the kidney or liver or heart that could have kept them alive. Another 18 people will die today. And another 18 tomorrow. And another 18 every day, until Congress fixes the law that causes so many valuable organs to be wasted, and so many lives to be needlessly lost.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter