MITT ROMNEY could learn a lesson from Sen. Ted Kennedy, the man he wants to unseat.

As he campaigns for a sixth full term in the US Senate, Kennedy is unblushingly letting himself be Kennedy. At this late stage of his career, America's national monument to 1970s-style Democratic liberalism is not about to reinvent his ideology. Kennedy has been wrong about most things for as long as I can remember -- he entered the Senate before I entered kindergarten -- but I'll give him this: He knows what he believes in and doesn't hide it.

Kennedy rarely frets about whether his stand on an issue is politically popular. Indeed, the older he gets, the more hard-core he becomes. "In recent years," observes The Almanac of American Politics 1994, the respected reference book on Congress, "his record has been increasingly radical, at the farthest left edge of Senate opinion."

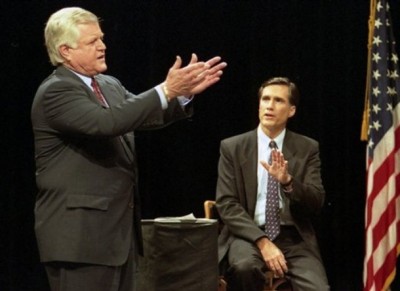

Sen. Ted Kennedy and Republican challenger Mitt Romney |

From supporting forced busing to opposing capital punishment, from his assault on Jimmy Carter to his assault on Robert Bork, from his fondness for Leonid Brezhnev to his contempt for term limits, Kennedy has nearly always played the lock-step leftist. He hasn't worried about offending voters, he hasn't hesitated to attack those he disagrees with, and he hasn't toned down his rhetoric to avoid being divisive.

And -- so far -- he hasn't lost a reelection fight.

To be sure, Kennedys in Massachusetts have been able to get away with things that would be ruinous for mere mortals. How much of a residual "Kennedy mystique" still exists among Bay State voters is something that (a) nobody can measure accurately, and (b) Romney can't do anything about anyway.

What Romney can do is stop campaigning so cautiously and carefully, like a front-running candidate afraid of slipping up. For all the chatter about Kennedy's being in the fight of his life, Romney is still very much the long shot. A long shot doesn't win by playing it safe, he wins by racing his heart out. So far, that is not a description one could apply to candidate Romney.

At a recent working lunch with Boston Globe editors and writers, Romney looked good, spoke well, remained poised -- and came down firmly on both sides of almost every issue.

He derided Kennedy's shrinking ability to bring federal dollars into the commonwealth ("I look at Massachusetts and I don't see the evidence of an incredibly effective, high-clout senator who's really bringing home what needs to be brought to Massachusetts"). Then he derided the importance of snagging federal dollars in the first place ("I'm not campaigning on the proposition that if I'm elected to the Senate, I can bring more pork to Massachusetts").

He said he's against affirmative action quotas. Yet he also said he's against repealing the laws and regulations that mandate such quotas, like the misnamed Civil Rights Act of 1991, which Kennedy helped write.

He said cigarette taxes are too high and believes he opposed the 1992 ballot question raising them 25 cents a pack. But asked if that hike should be rolled back, Romney replied, "No."

He said he opposes US military involvement in Haiti or Bosnia. On the other hand, he said, it would be OK if the United States acted "as part of the world community."

He said he favors proposed legislation making it illegal to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. And in other cases -- a landlord with an apartment to rent, for instance? On that, said Romney, he doesn't take a position.

He said Americans pay far too much in taxes (and rightly gave some of the blame to Kennedy). But, he hastened to add, he's not about to propose a list of taxes he wants cut.

It's easy to declare that 32 years is long enough for any politician and that the time has come for Ted to step down. If a recent Boston Globe/WBZ poll is accurate, Romney shares that view with 52 percent of Massachusetts voters.

But Romney is timid about explaining what he would do with Kennedy's job if he had it. Inhibited by a fear of being (gasp!) controversial, he is tiptoeing through his campaign, determined to emit no "shockers" and antagonize no voters.

As a management consultant, a venture capitalist and a CEO, Romney built a luminous reputation on his ability to appraise a murky situation, decide on a course of action, and plunge ahead. "Of the thousands of companies I've looked at," he said in April, "I've been able to say: This will work, that will work, that won't work. My instincts are pretty good."

So where are those instincts now?

With one exception, Kennedy's reelection opponents have always run polite, don't-rock-the-boat campaigns; Kennedy has always blown them away with victory margins of around 70-30.

The exception was Ray Shamie. In 1982, the rags-to-riches novice campaigned hard as an unabashed conservative, embracing Reaganism in the middle of a recession and blasting Kennedy on issue after issue. Shamie disdained the middle of the road, yet he held Kennedy to barely 60 percent -- his lowest reelection margin ever. Six years later, against a genial, noncombative Joe Malone, Kennedy's vote soared by 450,000.

Good looks and upbeat TV spots won't put Mitt Romney in the US Senate. As long as he is more concerned with what voters think of him than with what he thinks of the issues, the smart money says Kennedy will win.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.