IT WAS the week of the Martin Luther King holiday, and the public library in Germantown, Md., was gearing up to host MoComCon, the annual Montgomery County Comic Convention. The day-long event celebrates "comics, graphic novels, and fandoms," according to the MoComCon website. It includes cosplay contests, kids' crafts, anime viewing, a dance party, Pokémon trivia, and "Superhero Storytime." And, of course, plenty of space for vendors to market their comic-related wares.

Looking through the convention website, reporter Mallory Wilson of The Washington Times discovered something: Vendors were being charged "different prices based on race and gender, with the highest prices reserved for businesses run by white men."

For a 6-foot table with two chairs and access to electricity, the website listed a rate of $325. But if the application was from a "woman- or minority-owned business," the charge dropped to $250.

When Wilson asked about the disparity, a Montgomery County spokesperson defended it. The pricing differential, she said, was intended to make the convention "as inclusive as possible" and to boost vendors who were "focused on trying to reach minority, Black, and brown communities." The executive director of Friends of the Library, the chief sponsor of MoComCon, approved as well. Charging different fees based on sex and skin color, Ari Z. Brooks told the Times, "reflects our joint commitment to promote inclusivity in library programming."

A vendor at a comic convention. |

Except that there is nothing "inclusive" about penalizing or rewarding people on the basis of their race and gender.

Nor is there anything ethical about it.

Nor is there anything legal about it.

To his credit, Montgomery County executive Marc Elrich — unlike his spokesperson — realized at once that the pricing scheme was unconscionable. When a reporter at a press briefing asked him about the Times story, he didn't equivocate. "If they're doing it, I can't see how that's not illegal," he said. "Different rates for different races? That is so old school, we are well past that day. . . . There's no way — I can't believe that."

Under Section 27 of the Montgomery County Code, it is illegal for any "owner, lessee, operator, manager, agent, or employee of any place of public accommodation" to discriminate on the basis of a dozen characteristics, including race, color, sex, or ancestry. That prohibition has been on the books since 1965. It was enacted, in other words, shortly after Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race and sex in any establishment engaged in interstate commerce. The Civil Rights Act, in turn, was grounded in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids any state to "deny to any person . . . the equal protection of the laws."

True to his word, Elrich promptly nixed the MoComCon pricing scheme. The revised vendor application for the convention (which was postponed because of weather to the first weekend in March) no longer differentiates illegally by race and sex. The charge for all vendors has been lowered to $175.

But while Montgomery County is no longer engaged in such wrongheaded "inclusiveness," the mindset behind the original plan is alive and well in countless other places.

Two generations after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, 60 years after King's timeless plea that Americans be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character, more than a decade and a half after the Supreme Court's ringing declaration that "the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race," the practice of sorting people by their physical characteristics persists.

Numerous jurisdictions and institutions continue to enforce racial and gender set-asides in contracting and hiring. The City of Boston blithely announces on its website that municipal procurement contracts are "available exclusively for minority- and women-owned businesses." The State of California requires that the boards of publicly-held corporations include a minimum number of "diverse" members. Almost as soon as racial preferences in college admissions were ruled unconstitutional last summer, journalists and experts began explaining how simple it would be to circumvent the ban.

Any number of corporations have adopted race-based approaches to managing their workforce. Some lay out the precise racial percentages that they want their staff to reflect. Others announce plans to increase their hiring of Black employees by a specified quota. Even some companies forced to shrink their payroll pledge that decisions about layoffs will be made through "an antiracist/anti-oppression lens."

Worst of all, intellectual justification for the very phenomenon that King and so many other civil rights heroes abhorred — treating individuals differently because of their color, sex, or other immutable characteristics — is now provided by people who claim to oppose racism.

"Racial discrimination is not inherently racist," asserts Ibram X. Kendi in his book on antiracism. "The defining question is whether the discrimination is creating equity or inequity. If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist." In case that isn't clear enough, he underscores the claim: "The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination."

That is a grievously false and destructive proposition. It was repudiated by civil rights champions from Frederick Douglass to W.E.B. DuBois to King. Racial discrimination for any reason, well-intentioned or ill-intentioned, is immoral. To reach a decision about anyone because of their race is by definition demeaning. It amounts to an assault not just against merit but against our common humanity. And far from speeding the day when invidious racial distinctions will be a thing of the past, it pushes that day ever farther down the road.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The day my father signed up for unemployment benefits

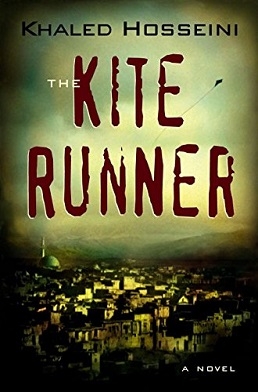

My father passed away three years ago this week and rarely does a day pass that I don't think of him. It is unusual, however, for me to be reminded of my father by a scene in a novel. That happened recently, as I was recently reading Khaled Hosseini's beloved modern masterpiece, "The Kite Runner."

Though it first appeared in 2003, the book was reissued for its 20th anniversary in a new edition with an afterword by the author. If you have never read "The Kite Runner," which has sold many millions of copies, you have a great and moving experience to look forward to.

Baba, a key character in 'The Kite Runner,' exemplifies the work ethic of immigrants to America. |

Without trying to summarize the book, I will mention that it is written in the form of a memoir. It tells the story of Amir, who grew up in a well-to-do neighborhood of Kabul before Afghanistan was invaded by the Soviet Union and taken over by the Taliban. At the heart of the novel is Amir's friendship with Hassan — a friendship he betrayed as a child and then, many years later, strove to redeem.

Scarcely less important to the "The Kite Runner," though, is the relationship between Amir and his father, Baba. In Kabul, Baba was a man of considerable importance in the community — a wealthy merchant, influential and highly respected. Though Amir knows that his father loves him, he is also painfully aware of his failure to meet his father's expectations. But the relationship between father and son gradually changes after they flee Afghanistan and settle in Fremont, Calif., a community with South Asian immigrants. Amir recounts with great sensitivity Baba's struggle to adapt to the change in his circumstances — from the wealthy local dignitary he used to be to the poor and struggling immigrant he has become. Baba finds a grubby job in a gas station, where he pulls "12-hour shifts pumping gas, running the register, changing oil, and washing windshields." It is a sorry comedown for someone who had known a very different life back in Afghanistan. But he accepts his lot with few complaints, willing — like numberless other immigrants in America's history — to work his fingers to the bone in order to ensure a better life for his child.

My father, too, was an immigrant to the United States. He came from Czechoslovakia after World War II, the only member of his family to emerge alive from the Nazi death camps. Unlike Baba, my father had been poor in the old country, so coming to America didn't represent a collapse in his economic and social status. But like the father in "The Kite Runner," mine had an unrelenting work ethic. When I was a child, I saw how he put in long days without complaint at a job I doubt he ever much cared for — he owned a furniture store in downtown Cleveland — in order to support his family.

This particular passage triggered a vivid memory. Amir describes going with his father to the welfare office in San Jose, where they meet with their case worker, Mrs. Dobbins.

Baba dropped the stack of food stamps on her desk. "Thank you but I don't want," Baba said. "I work always. In Afghanistan I work, in America I work. Thank you very much, Mrs. Dobbins, but I don't like it free money."

Mrs. Dobbins blinked. Picked up the food stamps, looked from me to Baba like we were pulling a prank. . . . "Fifteen years I been doin' this job and nobody's ever done this," she said. And that was how Baba ended those humiliating food stamp moments at the cash register and alleviated one of his greatest fears: that an Afghan would see him buying food with charity money. Baba walked out of the welfare office like a man cured of a tumor.

When I was about 12 or 13, my father's furniture store went out of business — there was too much crime and too few customers in the Cleveland neighborhood where he had stuck it out for so long. Later my parents would try again, opening a new store in Willoughby, Ohio, a suburb east of Cleveland. In the meantime, however, my father needed to pay the grocery and utility bills. He took me with him to the local government office, where he filled out the required paperwork and provided the necessary documentation to collect unemployment benefits.

I could see that the process made him miserable. He was used not only to pulling his own weight but to providing jobs for his employees. It tormented him that he could no longer keep the business going. It tormented him even more to take assistance from the government. That this was no handout — as a small business owner, my father had for years paid the employer's share of payroll taxes as well as unemployment insurance premiums — made no difference. To be on the receiving end, even for only a few weeks or months, went deeply against the grain.

As a child and even a young adult I never really thought about it, but in the lives of the immigrants among whom I grew up, there was a great insistence on dignity and self-respect. There was especially an unwillingness to be seen as a taker, even a taker of benefits to which they were entitled. The sentiment expressed by Baba — "I work always. In Afghanistan I work, in America I work" — was typical of the Eastern European men and women with heavy accents and Old World ways who were so prevalent among the adults I knew in my neighborhood, my synagogue, and my school.

One of the things I have always hated most about anti-immigrant nativism is the complaint that migrants "steal jobs" from US-born natives. Not only is it obviously false as a matter of observable fact — as the number of new arrivals has soared in recent years, the percentage of unemployed Americans has fallen — it is also false as a matter of emotional reality. The vast majority of foreigners who come to the United States have always come with the desire to work hard, improve their lot, and make a better life for themselves and their families.

For a number of years, on my daily commute to The Boston Globe, I would stop at a coffee shop next to a Home Depot. On my way in for a cup of caffeine early most mornings, I would see a group of young men standing together in the parking lot, regardless of the weather, conversing in Spanish as they waited hopefully for the contractors who often came by in search of laborers for the day. I'm familiar with the nativists' arguments — that the people who hire those men aren't paying taxes, that the workers are susceptible to exploitation, and so on. But I find so much more compelling the inherent dignity of those men, who preferred to work rather than take a handout, and who were willing to accept the risk of living in immigration limbo if that was the price of building a little American dream of their own.

My father was fortunate enough to be able to enter America legally. Once here, his top priority was to find work — his first job in America was nailing together window sashes — and he didn't stop working until he was in his 70s. Along the way he sold sewing machines and mattresses, ran a hamburger restaurant, became a furniture retailer, and, eventually, became a partner in a wholesale furniture warehouse. He worked all those years not just because he had a family to support, but because life without work would have been inconceivable. "I work always. In Afghanistan I work, in America I work." For a few weeks or months in the 1970s, when he had no choice, he collected unemployment insurance. Somehow I knew he hated to find himself in that position and clearly that knowledge made an impression. Now, decades later, I think back to that episode, and realize that, like so many of the things my father taught me, he conveyed the message without saying a word.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Charter schools offer a ray of hope" Feb. 1, 1998:

Applying for a charter is easier said than done. It took the parents hundreds of hours of research, calculation, and consultation — all on their own time and at their own expense. In January they submitted a proposal, blunt and blessedly jargon-free, to the state department of education. On Feb. 26, they will learn whether they made the final cut.

As word has spread of the type of school the North Bridge parents are planning, hundreds of families have signaled an interest. No surprise: Charter schools are the fastest-growing educational movement in America. In 1992 there was one such school; today there are more than 800, with an enrollment of more than 200,000 students — and tens of thousands waiting to get in.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I promise myself to realize without alloy the sweet enjoyment of partaking in the midst of my fellow-citizens the benign influence of good laws under a free government — the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers." — George Washington, Farewell Address (1796)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.