When Elizabeth Warren's claim to be American Indian came crashing down so spectacularly and embarrassingly last fall, more than a few observers wondered whether her presidential hopes had been irrevocably damaged. Clearly they weren't. Warren has emerged as the most formidable candidate in the Democratic field, and is currently the bettors' favorite to win the nomination.

But while the Native American DNA fiasco didn't torpedo her campaign, it impressed upon her how scrupulously honest she must be when talking about her life story. Or did it?

The Massachusetts senator no longer refers to herself as Cherokee, but in other ways her autobiographical revisionism continues.

On the campaign trail, Warren routinely introduces herself to audiences as someone who grew up yearning to be a teacher. After graduating from college, she was hired to work with kids suffering from learning disabilities and "got to live my dream of being a public school teacher ." But then, in Warren's telling, came a painful encounter with the reality of sexism in 1960s America. Here's how she recalled it at a Nevada rally last week:

So my first teaching position was as a special-needs teacher. I loved that job. But by the end of the first school year I was quite visibly pregnant and the principal didn't invite me back for the next school year.

So I found myself at home with the baby — yep, those were the days — and I got this idea that I could go to law school.

In the Democratic presidential debate last month, she told much the same story, though she worded it to make clear that she was dismissed from the classroom because she'd gotten pregnant.

I made it as a special-needs teacher. I still remember that first year as a special-needs teacher. I could tell you what those babies looked like. I had 4- to 6-year-olds.

But at the end of that first year, I was visibly pregnant. And back in the day, that meant that the principal said to me — wished me luck and hired someone else for the job.

So, there I am, I'm at home, I got a baby, I can't have a job. What am I going to do? Here's resilience: I said, I'll go to law school.

Thus Warren simultaneously plays the victim card, ingratiates herself with a powerful Democratic Party constituency (teachers unions), and evokes the "she persisted" theme that exhilarates her supporters.

But now, it turns out, there's a rather different explanation for why Warren left the "dream" job she loved so much. In 2007, when she was still teaching at Harvard Law School and her political career had not yet begun, Warren recorded an interview with historian Harry Kreisler for the web series Conversations with History . Asked about her early career, she says that she had entered college intending to be a regular classroom teacher, but had a change of heart.

I quickly switched over, and decided what I wanted to do was work with brain-injured children. So I got my degree in speech pathology and audiology, which meant I would be able to work with children who had head trauma and other kinds of brain injuries. And that's what I did.

I was married at 19 and graduated from college after I'd married, and my first year post-graduation I worked in a public school system with the children with disabilities. And I did that for a year, and then that summer I actually didn't have the education courses, so I was on an "emergency certificate," it was called. I went back to graduate school and took a couple of courses in education and said, "I don't think this is going to work out for me." I was pregnant with my first baby. So I had a baby and stayed home for a couple of years, and I was really casting about, thinking, "What am I going to do?" My husband's view of it was, "Stay home. We have children, we'll have more children, you'll love this." And I was very restless about it.

So I went back home to Oklahoma — by this point we were living in New Jersey because of his job — I went back home to Oklahoma for Christmas and saw a bunch of the boys that I had been in high school debate with and they'd all gone on to law school. And they said, "You should go to law school. You'll love it." I said, "You really think so?" And they said, "Of all of us, you should have gone to law school. You're the one who should've gone to law school." So I took the tests, applied to law school, and the day my daughter . . . turned 2, on her second birthday, I started law school at Rutgers Law School.

So Warren wasn't dismissed from teaching because she was pregnant. She wasn't a victim of unenlightened sexist thinking. She had only been hired in the first place on an "emergency certificate" and wasn't invited back because she "actually didn't have the education courses" required. By her own telling, she then enrolled in graduate school to get the necessary credentials, only to decide that pursuing an education degree wasn't "going to work out for me."

It's a perfectly respectable, even admirable, account of how she ended up in the world of law. But it has none of the aura of victimhood that contemporary candidates crave as a substitute for moral authority. Assuming Warren was telling the truth in 2007, and there is no reason to assume otherwise, the whole business about being given the boot because she got pregnant was concocted for political purposes. That probably doesn't matter to the besotted crowds at Warren rallies. But the senator's opponents may not be as willing to overlook her invention.

Elizabeth Warren continues to create fictions about her past. |

That isn't Warren's only latter-day concoction. She tells a real whopper about her political prospects when she first decided to run for the US Senate:

So I went back to Massachusetts and there was a Senate race coming up. A very popular Republican incumbent, who had a 65% approval rating, already had $10 million in the bank — and was cute. And so I started getting all these phone calls, and they said: "Elizabeth, you should run against him. You should run! You should run! You won't win, but you should run."

But [the reason why I wouldn't win] wasn't any of the other stuff I talked about. They just said, "Massachusetts is not going to elect a woman to that seat. It's just not going to happen, girl." So I thought about it, and I thought: Well, yeah, if a woman doesn't run, I guarantee a woman will never win.

I call BS.

In the fall of 2011, there may have been someone just waking from a 30-year coma who believed that Massachusetts voters would never send a woman to the US Senate. It is inconceivable that anyone else would have thought so.

By the time Warren jumped into the race against Senator Scott Brown, the "cute" incumbent, there was exactly nothing extraordinary about women holding statewide office. Three women — Evelyn Murphy, Jane Swift, Kerry Healey — had already been elected lieutenant governor. Three other women had successfully run for other top state positions: Shannon O'Brien was elected treasurer in 1998, Martha Coakley won the race for attorney general in 2006, and Suzanne Bump became the first female state auditor in the 2010 election. What's more, Therese Murray held the powerful position of state Senate president, Niki Tsongas was a member of the commonwealth's congressional delegation, Margaret Marshall had retired just a few months earlier after 11 years as chief justice of the state's Supreme Judicial Court, and US Attorney Carmen Ortiz was the influential federal prosecutor for Massachusetts.

Even before Warren formally entered the race, it was clear that she was a competitor to take seriously. As the Boston Globe's Joan Vennochi wrote in July 2011, Warren was "being touted as a Democratic star worthy of taking on Republican Senator Scott Brown." Within days of Warren's official campaign kickoff in September, another well-regarded Democratic candidate, Newton Mayor Setti Warren (no relation to Elizabeth), dropped out. The Globe reported that he had been "eclipsed" by the emergence of the combative, charismatic law professor and financial-industry scourge, who had "taken the spotlight since she entered the race."

A few weeks later, the only other serious Democrat running for the nomination, City Year founder Alan Khazei, was out as well. He was unable to compete with the "wave of enthusiasm" unleashed by Warren's campaign — enthusiasm that had attracted nearly $3.2 million to Warren's campaign in her first few weeks as a candidate.

So who, precisely, was telling Warren that "Massachusetts is not going to elect a woman to that seat"?

It was certainly true that a woman, Coakley, had failed to win the seat in 2010, when she and Brown competed in a special election to succeed the late Ted Kennedy. But that had nothing to do with Coakley's sex, and everything to do with the fact that she had run a complacent and inept campaign against a Republican who turned out to be especially warm and relatable. Well, maybe not everything: Brown's signature issue was his opposition to Barack Obama's proposed health-care overhaul, which at the time was deeply unpopular everywhere, including in Massachusetts.

Brown was popular, but Warren gained on him quickly. Ten days after she became a candidate, a statewide poll showed her leading Brown by 2 percentage points in the Senate race. In early December, a second poll found her in the lead by 7 points. For much of the following year, the race was regarded as a toss-up. It was never Brown's to lose, and anyone who suggested Brown was sure to win because his opponent was female would have been thought ridiculous. By the end of August, it was clear that momentum had shifted in Warren's favor: Of 19 opinion polls taken in Massachusetts in the last two months of the campaign, 14 gave Warren a decisive lead. When she won the election, 54-46, Massachusetts for the first time had a female US senator — a historic development, but in no way a startling one.

Against an opponent like Donald Trump, whose commitment to historical and autobiographical accuracy ranges from tenuous to null, Warren's fabrications may seem minor. But that's no guarantee that she can get away indefinitely with telling fictions about her career. For years she claimed to be a Native American — a claim that came back to bite her hard. Now she claims she was dismissed for being pregnant, and says she was told no woman could be elected senator from Massachusetts. Maybe those fabulations won't do her any harm. Or maybe they, too, will come back to bite her.

Wouldn't it be more prudent to tell the truth?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

'To Petition the Government'

Before leaving the subject of Elizabeth Warren, consider the latest in her continuing series of presidential-campaign "plans." On Wednesday, she published a proposal to tax businesses and trade organizations that spend significant amounts of money lobbying the federal government.

"Under my plan, we will end lobbying as we know it," declares Warren. She would insist, she says, on strictly enforcing a requirement that anyone paid to influence government register as a lobbyist. She would require lobbyists "to publicly report which agency rules they are seeking to influence and what information they provide to those agencies." And she vows to "shut the revolving door between government and K Street."

So far, so familiar, and not very different from what candidates, from both parties, have called for — and voted for — in years past. The real point of Warren's plan is to impose a stiff new tax on the exercise of a fundamental constitutional right:

My plan also calls for something unique — a new tax on excessive lobbying that applies to every corporation and trade organization that spends over $500,000 per year lobbying our government. This tax will reduce the incentive for excessive lobbying, and raise money that we can use to fight back against this kind of onslaught when it occurs.

Under my lobbying tax proposal, companies that spend between $500,000 and $1 million per year on lobbying, calculated on a quarterly basis, will pay a 35% tax on those expenditures. For every dollar above $1 million spent on lobbying, the rate will increase to 60% — and for every dollar above $5 million, it will increase to 75%.

Got that? If a company (or a group of companies) devotes more than half a million dollars on lobbying the federal government, Warren thinks it should be punished. In a Warren administration, communicating with the government — advocating changes in federal policy, discussing the impact of a proposed bill or regulation, complaining about enforcement, making a case for passing or defeating a pending measure — would be made significantly more expensive, and would therefore be significantly abridged.

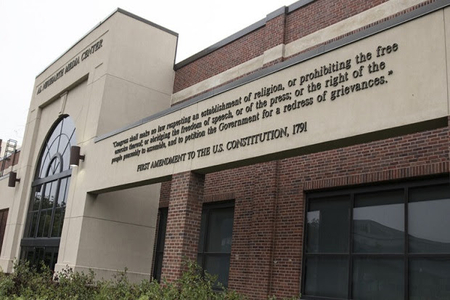

But there's a problem with abridging the freedom to lobby the government. The Constitution forbids it. It says so in the first sentence of the Bill of Rights: "Congress shall make no law . . . abridging . . . the right of the people . . . to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

In a government of, by, and for the people, the right to lobby — which is what "petition the Government for a redress of grievances" means — is about as fundamental as rights get. Citizens cannot be punished for approaching government officials with gripes, requests, objections, suggestions, petitions, and demands. As a law professor, Warren doubtless knows that her "plan to tax excessive lobbying" would never stand up in court. Like many of her vaunted "plans," it is a populist pose, not a serious policy proposal. It may be politically shrewd — as Peter Suderman remarks in Reason, lobbyists are "widely viewed as grubby and unseemly, if not actively corrupt" — but it is certainly fatally flawed.

The right of the people to 'petition the government for a redress of grievances' — that is, to lobby — is enshrined in the Bill of Rights |

Government cannot impose punitive taxes on "excessive" lobbying for the same reason it cannot use taxes to punish "excessive" publishing of newspapers, "excessive" church services, or "excessive" stumping for public office. They are shielded by the First Amendment — even from politicians eager to cast themselves as righteous warriors against rich and powerful special interests.

America's Founders knew what it was like to be denied the right to peaceably petition the government.

"The most alarming Process that ever appeared" was how Thomas Jefferson in 1774 described the order issued by Gen. Thomas Gage, Britain's military commander in Massachusetts, "declaring it Treason for the Inhabitants of that Province to assemble themselves to consider of their Grievances and form Associations for their common Conduct." It would be nice if Massachusetts's senior senator knew something about the history of the commonwealth she represents in Congress.

Anyone who really wants to reduce the role of lobbyists in American politics would make it a priority to reduce the scope and dominance of government. If Washington's horde of lawmakers, regulators, and administrators didn't exercise such immense authority over every aspect of our lives and livelihoods, there would be far less need for lobbyists who were able to influence that authority.

Washington has insinuated itself into a thousand-and-one decisions that individuals or local governments are more than capable of making for themselves. Which medicines can you buy? How efficient should your lightbulbs be? Can your children's school day begin with a prayer? Who qualifies for a mortgage? When do unemployment benefits run out? Can you pay an employee what his labor is worth? Should abortions be restricted? Is health insurance optional? Do artists require subsidies? Should broadcast licenses be awarded on the basis of race and sex? Must you purchase health insurance?

In Federalist No. 45 , James Madison emphasized that under the Constitution, the powers of the federal government "are few and defined," while those left to states and local communities "are numerous and indefinite." For the first 150 years or so of our history, that was largely the case. But New Deal/Great Society liberalism has turned the Framers' careful arrangement inside out. Today, there is almost nothing in American life that Washington does not consider itself fit to regulate, control, ban, tax, or mandate. Consequently, there is almost no area of American life in which people don't feel they must "petition the government" — lobby — to protect themselves and their interests.

Their right to do so is enshrined in the Constitution. Elizabeth Warren's right to tax them into nonexistence is nonexistent.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter