A standard tactic on the Democratic left these days is to cry "Sexism!" when anyone criticizes a liberal female candidate or points out her political weaknesses. Elizabeth Warren's liberal allies, many of them in the media, routinely deployed the "sexism" card in response to even the mildest negative appraisal during the Democratic primary campaign. So it was no surprise that Joe Biden's choice of Kamala Harris to be his running mate was instantly swaddled in dire predictions about the deluge of sexist attacks to come.

Indeed, even before Biden had named Harris, a group of prominent women affiliated with such left-wing organizations as Planned Parenthood, Emily's List, NARAL, and the National Women's Law Center fired off a memo to news organizations, warning that they would be guilty of sexism if in the course of the coming campaign they report on the ambition, likeability, electability, temper, appearance, leadership shortcomings, or political relationships of the Democrat's vice-presidential candidate — whoever she might be.

"We will be watching you," intoned the memo. "We expect change. We expect a new way of thinking about your role in how she is treated and the equality she deserves relative to the three men running for President and Vice President."

Some of those news organizations were already prospectively decrying such "sexist" outrages. The New York Times on Tuesday published an article denouncing "the strangely enduring criticisms that travel with women in politics," such as a reputation for having too much ambition, or for rubbing people the wrong way. On Friday, NBC News ran an essay by University of Pennsylvania professor Anthea Butler bewailing "the attacks and criticisms" being leveled at Harris: "She's 'extraordinarily nasty.' She's 'a cop.' She's too conservative — or she's too liberal. She changes her mind constantly."

Only bigotry towards women, Butler suggested, could explain such disapproval: "Funny how a competent, successful woman accomplishing something heretofore unprecedented seems to do that to people."

All these criticisms are routinely leveled at male politicians too, of course. John McCain's temper was much discussed during his 2008 run for the White House, and the flip-flops of John Kerry were exhaustively enumerated when he ran in 2004. But somehow these standard themes turn into "sexism" when the candidate is female. And Democratic.

Yet it wasn't that long ago that genuinely sexist attacks were lobbed at a woman who was running for national office, and few if any liberal journalists or feminist leaders seemed to care. Many, in fact, were doing the lobbing.

Journalists treated Sarah Palin's baby with Down syndrome as a reason to disparage her candidacy. |

When John McCain selected Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008, the nation got a good hard look at the way political opposition can fuel raw, ugly misogyny. Liberal hostility to Palin was understandable: She was a staunch conservative with undeniable charisma and the reputation of a reformer. For a while she seemed to have a brilliant future in national politics, and Democrats reasonably enough perceived her as a threat. But as I wrote at the time in the Boston Globe, much of the hostility to Palin was expressed in poisonously blatant sexual terms:

"Ideologically, she is their hardcore pornographic centerfold spread," Cintra Wilson wrote in Salon. "She's such a power-mad, backwater beauty-pageant casualty, it's easy to write her off and make fun of her. But in reality I feel as horrified as a ghetto Jew watching the rise of National Socialism."

On the website of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, commentator Heather Mallick was even cruder. Palin appeals to "the white trash vote" with her "toned-down version of the porn actress look," she wrote. "Husband Todd looks like a roughneck . . . What normal father would want Levi 'I'm a [bleeping] redneck' Johnson prodding his daughter?"

From radio talk-show host Randi Rhodes came the smutty suggestion that the governor of Alaska has an unhealthy interest in adolescent males: "She's friends with all the teenage boys," Rhodes told her audience last week. "You have to say no when your kids say, 'Can we sleep over at the Palins?' No! NO!"

Eve Ensler, the playwright best known for "The Vagina Monologues," described her "Sarah Palin nightmares" for the Huffington Post. She recalled how Republican delegates chanted "Drill, drill, drill!" when Palin called for more oil exploration in her speech at the St. Paul convention. "I think of teeth when I think of drills. I think of rape. I think of destruction. I think of domination. . . . I think of pain."

There was a lot more where that came from. CBS late-night star David Letterman sneered on the air that Palin looked like a "slutty flight attendant," while ABC's Jimmy Kimmel sniggered about seeing Palin "in high heels and a bikini [and] all of a sudden, I am for drilling in Alaska." One columnist called her "the closest thing Republican strategists could find to a man with a vagina."

These were not the supposedly sexist "tropes" that lurk in standard political analysis about a candidate's demeanor or ambition or likeability. They were gross and insulting examples of rank sexual objectification, and they surged through coverage of McCain's running mate like sewage through a drainpipe.

And even when the media purported to focus on Palin's suitability for the job, much of the criticism, as Tim Graham of the Media Research recalled this week, revolved around the fact that she had recently given birth to a baby with Down syndrome:

Within minutes, then-CNN reporter John Roberts suggested Palin might turn out to be a crummy mother: "There's also this issue that on April 18, she gave birth to a baby with Down syndrome. . . . Children with Down syndrome require an awful lot of attention. The role of vice president, it seems to me, would take up an awful lot of her time, and it raises the issue of how much time will she have to dedicate to her newborn child?"

Then-ABC anchor Bill Weir piled on, asking one McCain campaign aide: "Adding to the brutality of a national campaign, the Palin family also has an infant with special needs. What leads you, the senator and the governor to believe that one won't affect the other in the next couple of months?"

Then-NBC anchor Amy Robach asked, "If Sarah Palin becomes vice president, will she be shortchanging her kids, or will she be shortchanging the country?"

Washington Post columnist Sally Quinn suggested mothers can't handle the demands of the vice presidency: "Her first priority has to be her children. When the phone rings at 3 in the morning and one of her children is really sick, what choice will she make?"

In the 21st century, not even a hidebound conservative would challenge a Democratic woman's suitability for office on the grounds that she cannot simultaneously be a competent parent and an effective elected official. Even on the right, just about everyone recognizes that as a classic example of a sexist double standard — an objection no one ever raises about candidates who are fathers. That double standard was clear in 2008, too. But the target was Palin, so the rules were different.

To repeat, there were perfectly understandable reasons for liberals and Democrats to recoil from Palin's view and want her to be defeated. Again and again and again, however, they attacked her not just for her political opinions or her lack of knowledge, but explicitly in terms of her sex. When McCain picked Palin, women's activists didn't compile a 32-page "fairness guide" to non-sexist coverage of women in national politics, the way UltraViolet, Women's March, and other advocacy groups did this week in a preemptive defense of Kamala Harris. That only happens when a woman is named to a Democratic ticket.

Last week, Palin congratulated Harris and wished her well. "I hope," she said, "that the media will treat her candidacy not as personally rough as they treated mine." It was a gracious sentiment, but Harris has nothing to worry about.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Happy birthday, Thomas Sowell

This summer Thomas Sowell turned 90. If I had to choose a single living American whose work I wish were more widely known, it would be this remarkable economist and social thinker. Born in North Carolina during the Jim Crow era, he moved with his mother to Harlem when he was 9, and though he left high school after 9th grade, he eventually earned degrees from Harvard, Columbia, and the University of Chicago. His many years among the intelligentsia left him with a deep-seated antipathy to the arrogance and cluelessness of overeducated elitists — and particularly to their unshakable conviction that they have the insight and wisdom to organize the lives of millions of people about whom they know very little.

"Measured by his contributions to economics, political theory, and intellectual history, Thomas Sowell ranks among the towering intellects of our time," writes Coleman Hughes in the current issue of City Journal. The renowned playwright David Mamet has called Sowell "our greatest contemporary philosopher," but there is nothing rarified, incomprehensible, or abstruse about his work. Unlike countless academics, Sowell writes and speaks in plain English, and his essays, books, and interviews are a pleasure to encounter. He is plainspoken in part because it is in his nature, and in part because he is a gifted teacher. But I imagine that another reason Sowell is always at pains to express himself so clearly is because he knows how much damage can be inflicted under the cover of vague and imprecise language.

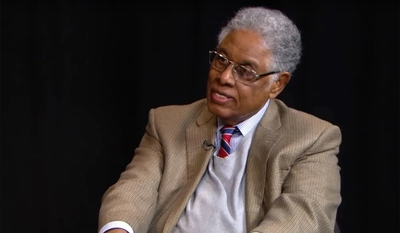

Thomas Sowell, "our greatest contemporary philosopher," is 90 years old. |

"Undefined words have a special power in politics," writes Sowell in the opening chapter of his outstanding 2011 book, Economic Facts and Fallacies,

particularly when they invoke some principle that engages people's emotions. "Fair" is one of those undefined words which have attracted political support for policies ranging from Fair Trade laws to the Fair Labor Standards Act. While the fact that the word is undefined is an intellectual handicap, it is a huge political advantage. People with very different views on substantive issues can be unified and mobilized behind a word that papers over their differing, and sometimes even mutually contradictory, ideas. Who, after all, is in favor of unfairness? Similarly with "social justice," "equality," and other undefined terms that can mean wholly different things to different individuals and groups — all of whom can be mobilized in support of policies that use such appealing words.

Sowell is brilliant at explaining the fundamentals of economics and clarifying where so much economic commentary goes wrong. Besides Economic Facts and Fallacies, I admire and have often consulted his jargon-free guide to economic principles, Basic Economics . But in recent years, Sowell's writings on race — and his vigorous challenge to politically-correct nostrums about racial bias, "diversity," and affirmative action — have become even more invaluable than his work on economics.

"A frequent theme in Sowell's writing is what philosophers would call reversing the explanandum — the phenomenon to be explained," observes Hughes in his City Journal essay:

Sowell's great contribution to the study of racial inequality was to reverse the explanandum that has dominated mainstream thought for over a century. Intellectuals have generally assumed that in a fair society, composed of groups with equal inborn potential, we should see racially equal outcomes in wealth, occupational status, incarceration, and much else. That racial disparity is pervasive is seen either as proof that racial groups are not born with equal potential or that we don't live in a fair society. The first position predominated among "progressive" intellectuals in the early 20th century, who blamed racial disparity on genetic differences and prescribed eugenics as a cure. The second has dominated the academy since the 1960s and is now orthodoxy on the political Left. Democrats as moderate as Joe Biden have charged that America is "institutionally racist," and when asked to prove it, the reply almost always points to statistical disparities between whites and blacks in wealth, incarceration, health, and in other areas. The suppressed premise — that statistical equality would be the norm, absent racism — is rarely stated openly or challenged.

In a dozen books, Sowell has challenged that premise more persuasively than anyone. One way he pressure-tests this assumption is by finding conditions in which we know, with near-certainty, that racial bias does not exist, and then seeing if outcomes are, in fact, equal. For example, between white Americans of French descent and white Americans of Russian descent, it's safe to assume that neither group suffers more bias than the other — if for no other reason than that they're hard to tell apart. Nevertheless, the French descendants earn only 70 cents for every dollar earned by the Russian-Americans. Why such a large gap? Sowell's basic insight is that the question is posed backward. Why would we think that two ethnic groups with different histories, demographics, social patterns, and cultural values would nevertheless achieve identical results?

Sowell notes, too, the cases of a minority group with no political power nevertheless outperforming the dominant majority oppressing them. His favorite example was the successful Chinese minority in Southeast Asia. But he also has written about the Jews in Europe, the Igbos in Nigeria, the Germans in South America, the Lebanese in West Africa, and the Indians in East Africa. Perhaps the most striking American example is the Japanese. The Japanese peasant farmers who arrived on America's western coast in the late 19th and early 20th centuries faced laws barring them from landownership until 1952, in addition to suffering internment during World War II. Nevertheless, by 1960 they were out-earning white Americans. . . .

One can object that the experience of black Americans is unique, and therefore incomparable with that of any other group. No other ethnic group in America was enslaved, disenfranchised, lynched, segregated, denied access to credit, mass-incarcerated, and so on. This is true enough — but only if our analysis is limited to America. What is so valuable about Sowell's perspective is precisely its international scope. In three thick volumes published in the 1990s — Conquests and Cultures, Migrations and Cultures, and Race and Culture — he examined the role that cultural difference has played throughout world history. Sowell documents the fact that slavery, America's "original sin," has existed on every inhabited continent since the dawn of civilization. Without going back more than a few centuries, every race has been either slaves or enslavers — often both at once. Preferential policies provide another example. What we Americans euphemistically call "affirmative action" has existed longer in India than in America. Malaysia, Sri Lanka, China, and Nigeria have all had it, too.

How does all this apply to America? On William F. Buckley's Firing Line, Sowell summed it up in a sentence: "I haven't been able to find a single country in the world where the policies that are being advocated for blacks in the United States have lifted any people out of poverty."

Sowell expresses these views not only with conviction backed up by depths of historical and cultural research, but from personal experience. In an essay a year and a half ago, he wrote about a black high school dropout who left home in 1948:

He had no skills, little experience, and not a lot of maturity. Yet he was able to find jobs to support himself, to a far greater extent than someone similar can find jobs today.

I know because I was that black 17-year-old. And, decades later, I did research on economic conditions back then.

Back in 1948, the unemployment rate for 17-year-old black males was just under 10 percent, and no higher than the unemployment rate among white male 17-year-olds.

How could that be, when we have for decades gotten used to seeing unemployment rates for teenage males that have been some multiple of what it was then — and with black teenage unemployment often twice as high, or higher, than white teenage unemployment?

Many people automatically assume that racism explains the large difference in unemployment rates between black and white teenagers today. Was there no racism in 1948? No sane person who was alive in 1948 could believe that. Racism was worse — and of course there was no Civil Rights Act of 1964 then.

Given the ubiquity of racism in 1940s America, what explains such low unemployment rates for black males? Why was there virtually no racial difference? Sowell's answer: In 1948, for all practical purposes, there was no minimum wage law to price unskilled and inexperienced workers out of a job.

As a black teenager, I was lucky enough to be looking for jobs when the minimum wage law was rendered ineffective by inflation. I was also lucky enough to have gone through New York schools at a time when they still had high educational standards.

Many of the seemingly compassionate policies promoted by the progressives in later years — whether in economics or in education — have had outcomes the opposite of what was expected. One of the tragedies of our times is that so many people judge by rhetoric, rather than by results.

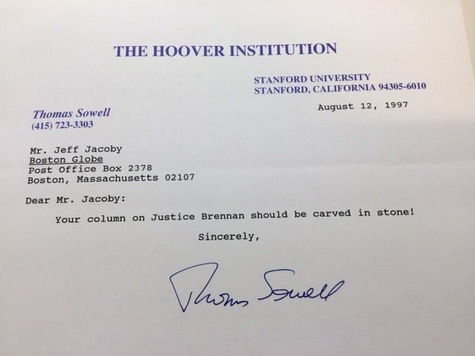

I never had the pleasure of meeting Sowell, and though I wish him many more happy birthdays, don't suppose I'll get that opportunity. But a documentary on his life and thought is in production, and I look forward to viewing it when it comes out next year. In the meantime, there are still plenty of Sowell columns I haven't yet had the chance to read, not to mention Sowell interviews I haven't yet watched. And then there is my all-time favorite piece of writing by Sowell: a one-line letter that arrived in my mail 23 years ago this month:

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Mediocrities everywhere, I absolve you. I absolve you. I absolve you. I absolve you. I absolve you all" — F. Murray Abraham, as Antonio Salieri, in Amadeus (1984)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter or on Parler.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.