GEORGE BUSH drew attention when he parachuted out of an airplane over Yuma, Ariz., a few months ago. But that isn't all the former president has been up to.

Writing in The Wall Street Journal last week, Jeffrey Taylor reported that "in the four years since he left office, Mr. Bush, already a wealthy man, has earned millions of dollars speaking publicly for about 40 companies. He has traveled to China for corporate employers at least eight times. . . . He usually charges $100,000 for trips abroad and $80,000 for domestic appearances, plus expenses. . . . For this, Mr. Bush generally restricts himself to giving speeches and rubbing shoulders with corporate executives and high-level government officials."

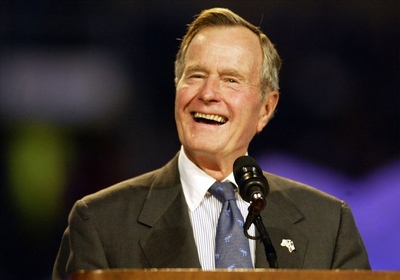

As he gives speeches for a fee of $80,000 and up, former President Bush has a lot to smile about. |

Among the firms that have paid Bush's $80,000-and-up speaking fee are Citibank, Goldman Sachs, Atlantic Richfield, and Dow Jones. He has spoken five times to the Women's Federation on World Peace, an organization founded by the wife of Sun Myung Moon, the leader of the Unification Church. Bush's spokesman, James McGrath, says that the federation and Moon's church are "separate and distinct," though it isn't clear that it would make any difference to Bush if they weren't.

The 41st president is doing what most of his predecessors would have never done: cashing in on the presidency. Jimmy Carter, for all his flaws, has not devoted his retirement to amassing riches. Richard Nixon, for all his flaws, wrote serious books on politics and world affairs. Harry Truman flatly refused to give speeches for money. When he left office in 1953, wrote biographer David McCullough, "his only intention . . . was to do nothing — accept no position, lend his name to no organization or transaction — that would exploit or 'commercialize' the prestige and dignity of the office of the president."

Truman's principled stand would strike Bush as incomprehensible. But then, Bush has never been a man of principle. Politeness, yes. Duty, yes. Loyalty, yes. But not principle. In Bush's mind, political ideals and core beliefs are things one refers to in State of the Union messages or invokes on the campaign trail — not things one actually takes to heart.

That was why Bush could utter the most famous ironclad vow in modern presidential politics ("Read my lips: No new taxes") and break it two years later. It was why he could anathematize a monster like Saddam Hussein ("Hitler revisited" . . . "worse than Hitler"), then leave Saddam's dictatorship intact and refuse to force him from power.

And it was why he so often came across as embarrassed or flighty or incoherent when he tried to address morally serious subjects.

During a visit to Auschwitz in 1987, what came out of Bush's mouth was, "Boy, they were big on crematoriums, weren't they?" In 1990, he told a group of students, "So, we're now coming into a new period. We look around the world, and we see the darndest, most dramatic changes moving toward the values that — that have made this country the greatest — freedom, democracy, choice to do things — you know." Reflecting on the value of prayer in a 1992 New Hampshire speech, he explained, "You cannot be president of the United States if you don't have faith. Remember Lincoln, going to his knees in times of trial and the Civil War and all that stuff. You can't be — and we are blessed. So don't feel sorry for — don't cry for me, Argentina."

For four years (12 counting Bush's term as vice president), Americans had to listen to endless amounts of this fractured, frantic babbling. Bush's oratorical powers, it is fair to say, did not exactly bowl them over. So why are Fortune 500 corporations anteing up $80,000 to $100,000 a pop — plus expenses — for the privilege of hearing him give speeches?

In his Wall Street Journal article, Taylor quotes from the annual report of IMC Global, an Illinois corporation that hired Bush to speak at a function it held in Beijing in September 1995. "Two months later," the company's report gloats, "an unprecedented full-year agreement for the sale of diammonium phosphate" — a chemical fertilizer — "was reached with Sinochem, China's central buying agency."

In short, IMC paid Bush three times the yearly salary of the median American family to make an appearance because it wanted to impress the Chinese into buying fertilizer. It wasn't Bush's ideas that IMC paid for. It wasn't his speech. It certainly wasn't his fertilizer expertise. It was his status as a former president of the United States. IMC wanted to leverage the dignity of the Oval Office to make a sale. And Bush was happy to rent it to them — for a price.

Ronald Reagan started this disgraceful business in 1989, when he took $2 million from Fujisankei, a Japanese media giant, to give two speeches and attend an awards dinner. Gerald Ford has accepted a slew of invitations to join corporate boards — and accepted the five- and six-figure fees that go with membership. Now Bush's tour of the lecture circuit takes post-White House avarice to a new level.

A few weeks back, Bush refused an invitation to return to Yale, his alma mater, for a day planned in his honor. His spokesman claimed that "between parachute jumps and economic summits and all," Bush was just too busy to attend. Perhaps Yale should have offered him $80,000.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.