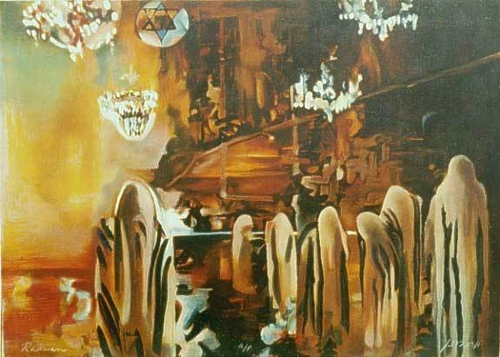

The singular promise of Yom Kippur comes from the Book of Leviticus. Chapter 16 prescribes the elaborate sequence of offerings and rituals carried out in ancient times by the High Priest, who was required to publicly atone three times — first for his own transgressions, then for those of his fellow priests, then for the entire nation. Today, there are no sacrifices and no High Priest; they were replaced 2,000 years ago with communal prayer and readings from the Torah. Still, the outcome of the Yom Kippur service is a guarantee of forgiveness: "From all your sins before God shall you be cleansed."

But there's a catch.

The absolution effected by Yom Kippur, the Jewish sages taught, applies only to sins one commits against God. For sins committed against fellow human beings, however, there can be no divine forgiveness until and unless the wrongdoer first seeks forgiveness from those he injured. Many Jews, in fact, do exactly that during the runup to the High Holy Days, approaching friends, acquaintances, colleagues, even (or especially) family members and asking their pardon for having done things that caused pain or gave offense.

There are many ways to sin against others, of course, including theft, violence, and breach of trust. Those transgressions are included in the formal confession that is a central element of the Yom Kippur liturgy — a long and detailed catalogue of offenses repeated again and again during the day. But by far the greatest number of sins listed, fully one-fourth of the total, are those rooted in words: "For the sin we have committed through speech . . . committed through scorn . . . committed through derogatory language . . . committed through gossip . . . committed through lying."

Dozens of transgressions are included in the formal confession that is a central element of the Yom Kippur liturgy. But by far the greatest number of sins listed, fully one-fourth of the total, are those committed with words. |

The sins we commit against others with words are the defining sins of our age. Never within living memory has our public discourse been so toxic, cruel, and shrill. Norms of civility and restraint once taken for granted have been replaced by malice, venom, and routine character-assassination. The understanding that reasonable people can disagree reasonably, even about profound and emotional issues, is essential to the health of a free society. Yet in recent decades, that understanding has shriveled up and blown away. In its place we have a culture of unbridled hostility and verbal violence, an embrace of hatred as a political virtue, and an eagerness to cancel careers and ruin reputations because of an out-of-favor opinion, a thoughtless joke, or a "wrong" headline.

The just-passed anniversary of 9/11 awakened memories not only of that day's horror but also of the widespread unity and mutual support it called forth. In an eloquent speech last week, former president George W. Bush recalled how Americans by the millions responded to the shock and evil of the terrorist attacks by reaching toward each other, for a time, with solidarity, grace, and selflessness.

That goodwill didn't last. "Those days seem distant from our own," Bush said. "A malign force seems at work in our common life that turns every disagreement into an argument, and every argument into a clash of cultures. So much of our politics has become a naked appeal to anger, fear, and resentment."

You don't have to be Jewish to recognize how much harm is done by the sins we commit against one another — above all, by the words we use in talking (or texting or tweeting or posting or publishing or writing or emailing) to and about one another. You don't have to be religious to know that no good can come of our vanishing ability to find common ground. You don't have to observe a Day of Atonement to wish there were more forgiveness in our world.

But the world won't change unless we change ourselves. However much it goes against the grain, we need to communicate more sympathy and less anger, to balance our own passionate convictions with greater forbearance toward others. It isn't an easy aspiration — Lord knows I often fall short — but Yom Kippur is an annual reminder that if we don't try, we are headed for disaster. Heaven will not smile upon us if we won't even try to smile upon each other.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.