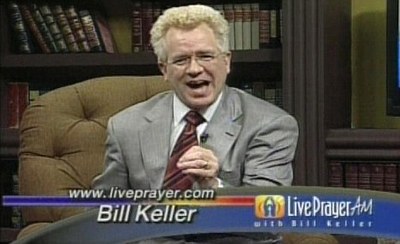

IN 2007, a prominent Florida televangelist named Bill Keller condemned Mitt Romney's religion in a "daily devotional" to his 2.4 million e-mail subscribers.

This Bill Keller demeans other people's religious beliefs. |

"If you vote for Mitt Romney, you are voting for Satan!" Keller raged. "There is no excuse, no justification for supporting and voting for a man who will be used by Satan to lead the souls of millions into the eternal flames of hell!".

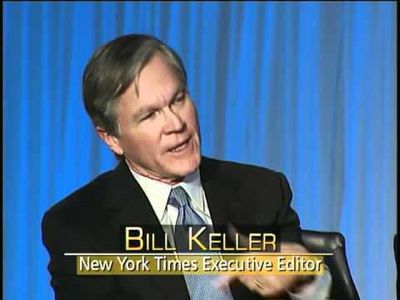

That was ugly, offensive, and intolerant. So was another diatribe about religion, published by a different Bill Keller last week.

"I honestly don't care if Mitt Romney wears Mormon undergarments beneath his Gap skinny jeans," the executive editor of The New York Times wrote in a smug essay for the Sunday magazine, "or if he believes that the stories of ancient American prophets were engraved on gold tablets and buried in upstate New York, or that Mormonism's founding prophet practiced polygamy. . . . Every faith has its baggage, and every faith holds beliefs that will seem bizarre to outsiders."

Keller the televangelist abominates Mormonism on explicitly theological grounds. His language in 2007 was far harsher than most of us would ever think of using when discussing the religion of other Americans.

Yet demeaning someone else's faith can take forms other than calling it satanic. Keller the Times editor argues that presidential hopefuls should be asked "tougher questions about faith," since their religious views may be relevant to how they would perform in office. Yet from his mocking opening line -- "If a candidate for president said he believed that space aliens dwell among us, would that affect your willingness to vote for him?" -- to his sniggering reference to "Mormon undergarments," Keller suggests that he is less interested in seriously understanding how religion influences the candidates' political views than in caricaturing and sneering at the faith of the conservatives in the 2012 field.

It is time to stop being so "squeamish" about "aggressively" digging into politicians' religious convictions, Keller writes. He advises journalists to "get over" any "scruples" they may have "about the privacy of faith in public life." Republican public life, that is -- specifically the "large number" of GOP candidates who belong to churches that many Americans find "mysterious or suspect."

It isn't only Romney's Mormonism that makes Keller twitchy. He frets that Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann are "affiliated with fervid subsets of evangelical Christianity" and that Rick Santorum "comes out of the most conservative wing of Catholicism." He has "concerns about their respect for the separation of church and state, not to mention the separation of fact and fiction." Above all, he wants to know "if a candidate places fealty to the Bible, the Book of Mormon . . . or some other authority higher than the Constitution and laws of this country."

So does this Bill Keller. |

Liberal elites like Keller are haunted by the specter of right-wing theocracy. When they see Christian conservatives on the campaign trail, they envision inquisitions and witch hunts and the suppression of liberty. They dread the prospect of a president respecting any "authority higher than the Constitution," and regard ardent religious faith as the equivalent of belief in space aliens. "I do care," says Keller, "if religious doctrine becomes an excuse to exclude my fellow citizens from the rights and protections our country promises."

Of course religion can be abused and religious belief turned to evil purposes. Yet far from threatening "the rights and protections" of America's people, religious faith has been among their greatest safeguard. Far from disavowing any book or authority "higher than the Constitution," our presidents place their hand on a Bible and swear to uphold that Constitution -- "so help me God." We have had our religious villains. But vastly more influential have been the American champions of liberty and equality -- from Adams to Lincoln to King -- who appealed to God and the Judeo-Christian moral tradition for the rightness of their cause.

For good reason, the Constitution bans any religious test to hold public office in the United States. No one need be Christian to run for president. But neither should being Christian -- even an enthusiastic Christian -- be treated as a kind of presidential disqualification. "Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity," George Washington avowed in his Farewell Address, "religion and morality are indispensable supports." The sweep of American history bears out the wisdom in his words.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.