How the great abolitionist heroine of the 19th century would weep to learn that at the threshold of the 21st century, black chattel slavery still exists in this world. More than weep: Harriet Tubman's very heart would crack if she knew that almost no one, not even the descendants of the American slaves for whose emancipation she fought so desperately, seems to care.

Chattel slavery -- the buying and selling of human beings -- ended in the West in the 19th century. In the East, especially in the Arab-dominated nations of Sudan and Mauritania, slavery abounds. Tens -- maybe hundreds -- of thousands of black Africans have been captured by government troops and free-lance slavers and carried off into bondage. Often they are sold openly in "cattle markets," sometimes to domestic owners, sometimes to buyers from Chad, Libya and the Persian Gulf states.

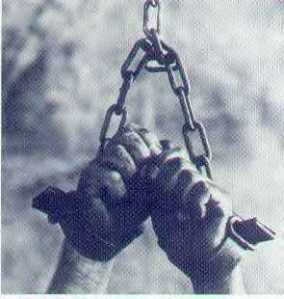

These people are slaves in every grim sense of the word. They are owned outright by their Arab Muslim masters. Many are branded like cattle, forcibly converted to Islam, lashed if they resist, tortured if they attempt escape. They are put to work as household servants or at hard labor in the fields. Girls and women are routinely raped. Kidnapped boys as young as 15 have been impressed into the Sudanese army, to be used as cannon fodder in Khartoum's "holy war" against the black Africans of southern Sudan -- and as blood banks for older soldiers.

Chattel slavery in Sudan and Mauritania has been conclusively and repeatedly documented by eyewitnesses, human rights investigators, the United Nations, Sudanese and Mauritanian defectors, and a handful of dogged journalists. Yet most Americans know nothing about it. Why? To end apartheid in South Africa, activists the world over kept up an unremitting campaign of pressure against the former government in Pretoria -- condemnation, vigils, sanctions, divestment, boycotts, marches, protests. Where is the campaign to free Africa's slaves?

"Every schoolchild in America knows that women have been raped in Bosnia," says Charles Jacobs, director of the Boston-based American Anti-Slavery Group. "Everyone knows the whales have to be saved. But no one seems to realize you can buy a black woman as a slave for as little as $15 in Khartoum."

Jacobs, a management consultant by profession, became a latter-day abolitionist in 1992 after an unsettling conversation with a client who worked out of Senegal.

"I had heard these rumors about slavery in the Arab world. I asked him, 'Can it be true?' He said, 'Sure it's true; you want to buy one?' "

Together with Mohamed Athie, an exiled Mauritanian diplomat, and David Chand, a black Christian from southern Sudan, Jacobs has spent 3½ years trying to shine a light on the horrors of slavery in North Africa. Almost everywhere they have turned -- the eminent human-rights agencies, the women's groups, the church councils, the civil rights coalitions -- they have encountered the same response: Yes, we know about the slaves. No, we're not prepared to fight for their freedom.

"For people who . . . have been at the forefront of the anti-apartheid movement," bewails Athie, "I seriously cannot understand how they can turn their backs on this. . . . I cannot believe people do not want to take action."

The new abolitionist movement has a few heroes. Several are black journalists from the nonmainstream media (some of them spurred to action by research from the American Anti-Slavery Group): reporter Samuel Cotton of the City Sun and publisher William Pleasant of the Liberator, both New York weeklies; Nate Clay of the New Metro News and WLS radio in Chicago; PBS television host Tony Brown. Gutsy Tim Sandler of the Boston Phoenix and Brian Eads of Reader's Digest have journeyed to Sudan to find escaped slaves and record their stories. Kevin Vigilante, a Rhode Island doctor and humanitarian, has tracked down the camps in Khartoum where abducted black children are brutalized. John Eibner's Christian Solidarity International raises funds to literally buy the freedom of captives in the slave markets of southern Sudan.

But these are rare exceptions. In most of America's prestige press, in the boardrooms of the great civil rights organizations, in the offices of famous black leaders, in the corridors of the State Department, one of the most bitter evils of our time evokes only a cowardly silence. Jesse Jackson cannot get involved in fighting slavery, one of his aides told Jacobs, because he "is busy with affirmative action." The NAACP hasn't acted. TransAfrica hasn't acted. The chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, US Representative Don Payne of New Jersey, recently dismissed the slave trade as a "sub, sub issue."

Only with aching slowness is this blackout being lifted. In May 1995, Jacobs convened an abolitionist congress in Harlem. Last month, a congressional subcommittee held a first-ever hearing on slavery in North Africa. But the pace of progress is microscopic. And all the while, tens of thousands of human beings are bleeding and dying in their chains.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Join the Fans of Jeff Jacoby on Facebook.