That America's founders were hypocrites, above all on the subject of race, is an enduring charge.

Examples are legion. At a Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society rally in 1854, an impassioned William Lloyd Garrison condemned the Constitution -- which extolled "the Blessings of Liberty," yet permitted slavery -- as "a covenant with death, and an agreement with hell." When a bill requiring public school students to recite parts of the Declaration of Independence was proposed in the New Jersey legislature in 2000, it was denounced as insulting. "You have nerve to ask my grandchildren to recite the Declaration," one black lawmaker erupted angrily. "How dare you?"

In 1975, in an essay marking the approach of the nation's bicentennial, the historian John Hope Franklin accused the Founders of "betraying the ideals to which they gave lip service." It was obvious, he wrote, that "human bondage and human dignity were not as important to them as their own political and economic independence."

Are the Founders guilty as charged? There is no denying that the patriots who proclaimed it "self-evident" that "all men are created equal" tolerated black slavery. It is true that the Declaration of Independence, which so stirringly affirms that God endows every human being with "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," was the work of a Virginia planter who owned 200 slaves.

So, yes, it is easy to damn Jefferson and the other Founders for not living up to their highest ideals. But if that is all it takes to be convicted of hypocrisy, how many of us could escape conviction? Surely what is more remarkable about Jefferson is not that he owned slaves, but that he acknowledged forthrightly and repeatedly that slavery was wrong. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, for instance, he characterized slaveownership as "the most unremitting despotism" -- an outrage bound to provoke divine wrath. "Indeed," Jefferson wrote, "I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever."

The Founders weren't stupid. Of course they knew that the universal ideals embraced in the Declaration were not matched in reality across the 13 colonies. The controversy over slavery was intense; but even more intense was the need for a united front against Great Britain. The choice that had to be made in 1776 was not between slavery or abolition. It was between hanging together, as Benjamin Franklin supposedly quipped in Philadelphia, or most assuredly hanging separately. They chose to hang together, and the confrontation over slavery was postponed for later.

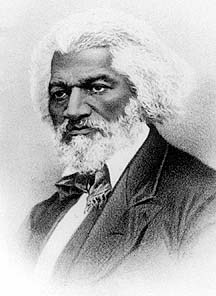

Frederick Douglass: "Are the great principles . . . embodied in that Declaration of Independence extended to us?" |

And in that confrontation, the lofty ideal of equality enshrined in the Declaration -- precisely because it was enshrined in the Declaration -- imparted enormous moral authority to the abolitionists' cause. Those who indict the Founders because their treatment of African slaves didn't come up to the standard of "all men are created equal" should be asked: Would the Declaration of Independence have been improved if those words had been omitted? Would slavery have ended sooner had abolitionists not been able to invoke that "self-evident truth"?

Inveighing against slavery on Independence Day in 1852, Frederick Douglass famously asked: "What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?" It was a "sham," he answered, "empty and heartless . . . revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy." For after all, he demanded, "Are the great principles . . . embodied in that Declaration of Independence extended to us?" That Declaration could have been written without those great principles. But at what cost to Douglass and all who fought against slavery? And at what cost to the Civil Rights movement a hundred years later -- a movement that rested its appeal for justice on the commitment made by the Founders when they declared to the world that all men are created equal? In Martin Luther King's phrase, the Declaration was "a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir." The Founders' generation may not have been able to keep that promise in full. Yet how diminished America would be without it.

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal." The Founders chose those words not to describe the nation in which they lived, but a better, more just nation; the nation America could become. Their words became the American creed, the taproot of the American dream, as worthy of celebrating today as they were in 1776.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --