November 10, 1989: East Germans celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall |

But for my friend, such agreeable normality was still anything but commonplace. Under the Communists, he told me, no one would have strolled along Wenceslas Square after dark, and even during the day there were no impromptu streetcorner concerts. In a society in which police and informers were everywhere, people avoided calling attention to themselves, and at night Prague's most famous public space was usually a cheerless no-man's-land.

"To see it now like this -- it makes me a little emotional," he explained.

He was older than I was, a Czech physician in his 40s who had opposed the old regime and paid a steep professional price for his dissent. Like most people, he had come to see the Iron Curtain as a permanent fact of life. Over the years there had been attempts to dislodge the Communist governments Moscow maintained across Eastern Europe -- the East Germans had tried it in 1953, the Hungarians in 1956, the Czechoslovaks in 1968 -- but each uprising had failed, crushed beneath Soviet tanks.

"If you want a picture of the future," says an official of the totalitarian government in George Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-four," which was published soon after the Stalinist night had fallen on Eastern Europe, "imagine a boot stamping on a human face -- forever." Communism was forever, or so it seemed through much of the 20th century, as tyrannies calling themselves "people's republics" scrupled at nothing -- not tanks, not secret police, not torture, not relentless propaganda and control of all media -- to perpetuate their dictatorial rule and repress those who opposed it.

Early on, Lenin had characterized Communist governance as "power that is limited by nothing, by no laws, that is restrained by absolutely no rules, that rests directly on coercion." Against such ideological ruthlessness, what chance did freedom and democracy have? Whittaker Chambers, a one-time Soviet spy, famously repudiated the Communist Party he had served and became one of its most eloquent opponents, but even as he did so he was sure, as he testified in 1948, that he was "leaving the winning side for the losing side." Decades later, the French thinker Jean-Francois Revel published How Democracies Perish, in which he explained sadly that democracy was simply not structured to defend itself against an enemy as implacable and deceitful as Communism. "Perhaps in history democracy will have been an accident," wrote Revel, "a brief parenthesis which comes to a close before our very eyes."

And yet, against all odds and to the astonishment of the world, it was Communism that came to a close before our very eyes. Twenty years ago this season, Moscow's Eastern European satellites threw off their chains. In a matter of months, the Communist regimes in Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania were consigned -- as Ronald Reagan had foretold -- to the ash heap of history. But not even Reagan had imagined that the dominoes would fall so quickly, or that Moscow would stand aside and let them fall.

"I learned in prison that everything is possible, so perhaps I should not be amazed," said Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright who became Czechoslovakia's first post-Communist president. "But I am."

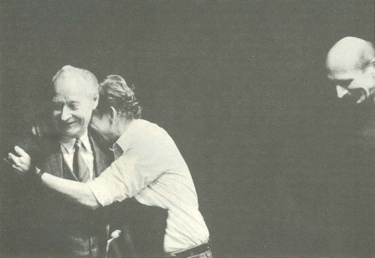

November 24, 1989: Václav Havel embraces Alexander Dubček, the Czechoslovak leader during the 1968 Prague Spring who was banished after the Soviet invasion. |

1989 exemplified with rare power the resilience of Western civilization. In our time, too, there are brutal despots who imagine that their power is unassailable: that their tanks and torturers can keep them in power forever. But the message of 1989 is that tyranny is not forever -- and that the downfall of tyrants can come with world-changing speed.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)