The worst pre-Holocaust calamity in Jewish annals -- the sack of the Second Temple by the Romans in A.D. 70 amid an orgy of slaughter -- was made vastly more deadly by the Jewish infighting that preceded it. Appeasers who favored surrender to Rome warred with zealots who preached resistance. The rift between the factions grew deep and savage. Jewish blood flowed in Jerusalem's streets long before the Romans breached her walls. The rabbis would later teach that the destruction of the Temple and the long nightmare of Jewish homelessness it ushered in were caused not by the military might of the Roman Empire, but by sin'at khinam: baseless hatred among Jews.

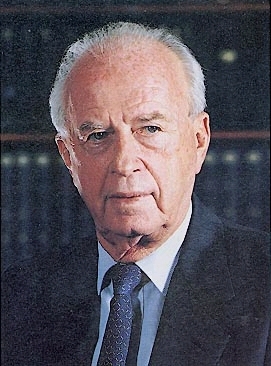

As the sickening murder of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin makes clear, sin'at khinam still envenoms the Jews and politics of Israel.

The Jewish fanatic who killed Rabin has plunged Israelis into the same shock and grief Americans felt when John F. Kennedy was cut down -- a stunned agony that knows no party and suspends, at least temporarily, all the polemics of politics. "The mind cannot take it and the heart weeps," said Benjamin Netanyahu on Saturday night. Netanyahu is head of the Likud Party and had been among Rabin's severest critics. But in that hour he spoke for all his countrymen.

Israelis are united now in mourning their leader. But there is no unity in Israel. The peace process that Rabin was celebrating in the hour of his death has divided Israelis more bitterly than any issue in their state's 47-year history.

Just over two years ago, mutterings first began that Israel was heading toward a civil war. Such talk then seemed paranoid and feverish. Today, as freshly turned earth covers Rabin's grave, it begins to sound almost plausible.

It is impossible to overstate how profoundly Israeli society has been riven by the Labor Party's peace process. The country is split in half. The split is not between those who favor peace and those who oppose it. It is between those who believe that giving up land to the PLO and Syria -- including land on which Israelis were encouraged to build homes and raise children -- is the only way to end Arab-Israeli enmity, and those who fear that such a formula represents a mortal threat to the Jewish state.

Those fears are not groundless. In the 25 months since Rabin and Yasser Arafat first shook hands on the White House lawn, scores of Israelis have died at the hands of Arab suicide bombers. Among radical Palestinians, the cry of "Death to the Jews" has only intensified. Arafat himself has repeatedly made speeches (in Arabic) praising terrorists and calling for martyrdom and jihad - holy war -- to "liberate" Jerusalem. No wonder half of Israel thinks the Labor government's peace process has been a dreadful mistake.

Only by the barest majority -- 61-59 -- did parliament vote last month to ratify the accord with the PLO. Two weeks earlier, a national poll found that 56 percent of Israelis rated the peace process "bad" or "very bad." The world applauded Rabin -- as now, heartsick, it eulogizes him -- for his willingness to reach out in peace to the Arab enemies he had fought for so long. The final tragedy of this man is that he could not extend the same hand of peace to his opponents at home.

Instead of allaying the fears of the many Israelis who opposed his concessions to Arafat, Rabin and his ministers demonized them. Settlers in the territories were "crybabies," he said, not "real Israelis." Peaceful protesters found themselves manhandled by Israeli police. Stories mounted of elderly women being roughed up in the streets, teen-agers being kicked and beaten. Rarely, said Ida Nudel -- a former Soviet prisoner of conscience who was called the "Angel of Mercy" for her self-sacrifice in the Gulag -- had the KGB treated dissidents the way Rabin's government was treating its opponents.

Rabin blasted an audience of immigrants, some of them noisy critics of his policies, as "racists" and "an embarrassment to Judaism." Foreign Minister Shimon Peres -- now the acting prime minister -- spurned hunger strikers as "undemocratic." Another minister called opponents of the government's policy "barbarians." The director-general of the foreign ministry excommunicated anyone who opposed financial aid to the PLO -- financial aid, yet! -- as an enemy of Israel.

"Such verbal violence tends to beget responses in kind," warned the Jerusalem Post. "Some settlers have shamelessly and despicably taken to calling government leaders liars, traitors, and murderers. . . . With national tensions reaching a breaking point, and with anxiety exacerbated by terrorist incidents . . . it can trigger physical conflict."

That warning appeared on Dec. 9, 1993. It ended thus: "It is time the government, and particularly Rabin himself, began to realize that maligning the settlers may gain political points with party followers; but ultimately such irresponsible rhetoric will endanger the very fabric of the nation."

And so now Yitzhak Rabin, a man of courage and patriotism and many virtues, lies dead by the hand of a fellow Jew. The ancient scourge of sin'at khinam -- hatred without cause -- has claimed another victim.