A statue of Christopher Columbus in Providence, R.I., was vandalized in 2019. |

IN 1997 I wrote a column for Columbus Day weekend that opened on a smart-alecky note: "Say," I asked, "is it OK to admire Christopher Columbus again?"

Ever since the quincentennial of Columbus's first voyage to the New World in 1492, denunciations of the Italian navigator as a brutal conqueror and bloody enslaver had been growing louder and more vehement. I didn't think much of the denouncers — "commissars of political correctness," I called them — and wanted to remind readers that there were good reasons why Columbus had been regarded by generations of Americans as a great man. To be sure, by present-day standards he was no sensitive, enlightened role model. Columbus was "a zealot, greedy and ambitious," I acknowledged, "capable of cruelty and deception." He and the Spaniards he led to the New World were vicious in their treatment of the indigenous people they encountered. But there was no denying his astonishing feats of seamanship or the world-changing impact of his discoveries. "For all his flaws," I concluded, "he was magnificent."

I wouldn't write that today. My view has changed.

In the past quarter-century, progressive attacks on Columbus's reputation have grown even more fervent. Statues of the explorer have been repeatedly vandalized or toppled. In at least 14 states and more than 130 cities, Columbus Day has been refashioned as Indigenous Peoples Day. Even Columbus, Ohio, no longer honors its namesake with a holiday. The Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote of Columbus in 1954 that "his fame and reputation may be considered secure for all time." But under the relentless pressure of revisionists, Native American activists, and woke iconoclasts, Columbus's prestige has been shredded and stomped on.

In general, I consider it dishonest and arrogant to measure individuals who lived centuries ago by standards that didn't exist in their day or to judge them pitilessly for behavior that we find detestable but that they and their world would have regarded as normal.

But what changed my mind about Columbus wasn't anything written or said by his modern detractors. It was the testimony of his contemporaries. I didn't realize in 1997 that Columbus's behavior toward the native peoples of the New World had indeed violated the principles of his own age. In fact, they violated the specific orders he had been given by Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, the Spanish rulers who authorized and financed his journeys.

Columbus returned from his first voyage to what he mistakenly called the Indies with a dozen abducted natives, as well as plans to capture and exploit many more. His first trip had been rushed, he told the monarchs, but on his next he was sure he could amass "slaves in any number they may order."

The king and queen ordered him to do no such thing. In written instructions dated May 12, 1493, they directed Columbus to "endeavor to win over the inhabitants" to Christianity and not harm or coerce them. He was to ensure that everyone under his command "shall treat the Indians very well and affectionately without causing them any annoyance whatever." In fact, they told Columbus, he should present gifts to the natives "in a gracious manner and hold them in great honor."

But the Admiral of the Ocean Sea had other ideas.

During his second journey to the Caribbean, historian Edward T. Stone wrote in a 1975 essay for American Heritage, Columbus captured a large number of indigenous men, women, and children, sending them back as cargo in 12 ships to be sold in the slave market at Seville. Anticipating that the royal couple might be outraged by his failure to comply with their orders, Columbus advised the captain transporting the native people to explain that they were cannibals lacking any language with which they could be taught the elements of Christianity. Surely it would be a kindness, Columbus contended, for such heathens to be "placed in the possession of persons from whom they can best learn the language."

Perhaps that ploy worked at first. But reports of the savagery, slaughter, and enslavement committed by Columbus could not be ignored indefinitely. In 1500, the Spanish sovereigns finally lowered the boom. They commissioned Francisco de Bobadilla to investigate and report on the admiral's conduct. After gathering information from Columbus's supporters and detractors, Bobadilla filed a no-holds-barred indictment detailing the cruelties committed by Columbus and his lieutenants.

"Punishments included cutting off people's ears and noses, parading women naked through the streets, and selling them into slavery," reported The Guardian when a copy of Bobadilla's statement was discovered in 2006 in a state archive in the Spanish city of Valladolid.

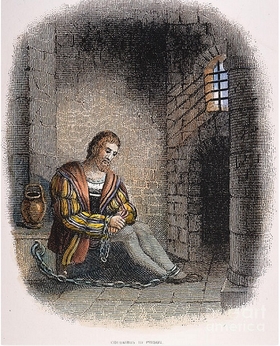

The charges were taken seriously. Very seriously: Bobadilla had Columbus arrested and shipped back to Spain — in chains — to stand trial. It was, in Stone's words, a "harsh and humiliating" downfall. Columbus eventually received a royal pardon, but Ferdinand and Isabella refused to restore his position as governor of the Indies.

It wasn't woke 21st-century progressives who first found fault with Columbus's actions. It was his contemporaries. Accusations of abuse by Columbus were taken so seriously that he was arrested in 1500 and sent back to Spain in chains to answer the charges against him. |

Another of Columbus's contemporaries to excoriate his deeds was Bartolomé de las Casas. He accompanied Columbus on his third voyage and participated in the violent suppression of indigenous people on the island of Hispaniola. Later he underwent a profound change of heart. Las Casas took holy orders, freed the people he had enslaved in 1514, and spent the rest of his long life passionately denouncing the "robbery, evil, and injustice" done by Columbus and the Spaniards who followed in his wake.

Five years ago I read Las Casas's most famous work, "A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies," which he published in 1542. It is ferocious in its wrath and graphic in its descriptions of the horrors inflicted on the native people. He raged against the sadism, greed, and treachery of the Spaniards. No one who reads his book can cling to the belief that condemnations of Columbus are nothing but 20/20 hindsight, or that they are based on moral standards by which no one in the 1500s would have judged him. His contemporaries did judge him by the standards of their age, and found him grievously wanting.

None of this is to deny Columbus's brilliance and courage as a mariner. His name will forever be linked to what Morison called "the most spectacular and most far-reaching geographical discovery in recorded human history." In 1997, I thought that was what mattered most about Columbus. I know better now.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter