Time for them to go

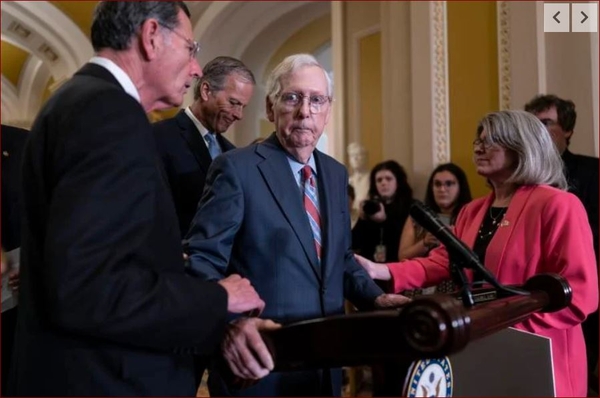

For the second time in five weeks, Senator Mitch McConnell suddenly froze up during a press conference, staring silently for half a minute or so before trying, unsuccessfully, to field more questions. Eventually his aides led him away from the cameras, as they had when something similar occurred on July 26.

Ironically, McConnell had just been asked whether he planned to run for reelection. He chuckled, seemed poised to answer, then abruptly stopped. He never did reply; his spokesperson said only that McConnell momentarily felt lightheaded while speaking with reporters and would consult with a doctor before his next event. On Thursday, his office released a letter from Congress's attending physician pronouncing him "medically clear" for work.

McConnell is old. He was born in 1942 and has been in the Senate for 38 years; in 2020 he was elected to his seventh six-year term. He is the longest-serving Senate Republican leader in the history of the GOP and the longest-serving senator ever elected from Kentucky. He has been in the Senate longer than all but one of its current members. Iowa's Charles Grassley, who has been a senator since 1981, heads the list. California's Dianne Feinstein, who took her seat in 1992, is in third place.

There are other prominent elderly members of the federal government. President Biden was also born in 1942 and his visible signs of age have grown so worrying that more than three-quarters of the public, according to the latest Associated Press poll, think he is too old to run for another term as president. Former House speaker Nancy Pelosi is 83. At least six House members are older than she is.

Washington is more of a gerontocracy than ever — no president has ever been older and the median age of the current Senate is 65.3 years, a record high. Though some House freshmen are in their 40s or younger, the median age in that chamber, too, is the highest it's ever been. McConnell's brain-freeze episodes, Biden's moments of obvious confusion, and the tragic evidence of Feinstein's cognitive decline keep raising questions about the age and health of America's political leaders. Actually, they keep raising just one question: What do we do about geriatric officeholders who refuse to relax their grip on power?

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell froze, speechless, during a news conference on Capitol Hill in July. It happened again last week when he met reporters in Covington, Ky. |

It is not a new conundrum. In "Master of the Senate," his spellbinding account of Lyndon Johnson's transformation into the youngest and greatest Senate majority leader in history, historian Robert Caro recounts how Capitol Hill's unwritten seniority system — the most powerful positions went to the longest-serving members — had become a "senility system."

For example, Caro describes Arthur Capper of Kansas, who became the ranking Republican member of the Agriculture Committee at the age of 75. By that point Capper was already deaf and so frail that one news account described him as "a living shadow, one hand cupped behind his ear and a strained expression on his face" as he struggled to follow a committee hearing.

"[I]n 1946 the Republicans became the majority party in the Senate," Caro continues, "and seniority elevated Capper, now 81, to Agriculture's chairmanship, although by that time, as another reporter noted, 'he could neither make himself understood, nor understand others.'"

Another example: Carter Glass, a Democrat from Virginia, took over the chairmanship of the Appropriations Committee in 1932, when he was 74. By 1942, he was so ill that he remained at all times in the Mayflower Hotel, never venturing to Capitol Hill. When some of his fellow Democrats proposed in 1945 that Glass, then 87, should step down, his wife replied on his behalf that the suggestion would not be considered.

Has anything changed? When Senator Ted Kennedy was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2008, it quickly became apparent that he would never again be well enough to do his job. After he had been absent from the Senate for 15 months, I wrote a polite column urging him to resign so that Massachusetts could again have two functioning senators. "Few things are harder for those accustomed to power than letting it go," I commented. "But there is no honor in clinging to office till the bitter end."

Needless to say, Kennedy did cling to office till the bitter end. Like 1 of every 6 senators ever sent to Washington, he hung on to his seat until death. So have other senators since then: Robert Byrd of West Virginia (died in office in 2010), Daniel Inouye of Hawaii (2012), Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey (2013), and John McCain of Arizona (2018).

Pelosi stepped down from the speakership this year, and it is conceivable that McConnell might decide — or be compelled by his caucus — to do the same thing. But the likelihood that he will agree voluntarily hang up his gloves and retire from the congressional ring altogether seems close to nil. If Carter Glass, Ted Kennedy, and Dianne Feinstein wouldn't go voluntarily, why should any other superannuated member of Congress?

The Constitution establishes no maximum age for senators, representatives, or presidents — only a minimum. Voters could refuse to elect or reelect a candidate who has lost the cognitive or physical stamina to serve in office, but they almost never do.

As with most problems in our democratic republic, the ultimate solution is in the hands of the people. All we have to do is tell our politicians: No more.

I don't know why that should be so hard. As a matter of policy, I routinely vote against incumbents, regardless of party. If my fellow Americans would join me in doing the same for a few electoral cycles, we'd have that gerontocratic deadwood cleaned out in no time. There is no guarantee that Washington would work better if there were fewer septuagenarians and octogenarians pressing the levers of power. But wouldn't it be refreshing to find out?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A 12-year-old's flag patch and the state of US journalism

Do you know what happened when school officials in Colorado Springs, Colo., decided to tread on a 12-year-old student who had a patriotic patch on his backpack?

Certainly you ought to know; the story made news last week and a video of it was viewed millions of times on social media. The episode was the latest flare-up on the culture war front lines; it highlighted the clash of values that has galvanized so many parents around the country into opposing what they regard as disrespect from "woke" school board members and administrators.

Whether you're familiar with the story or don't know the first thing about it most likely depends on where you get your news from.

If your main sources of information include newspapers, networks, and websites with a conservative or libertarian bent — National Review, Fox News, the New York Post, Reason, Washington Examiner, The New York Sun — then you are likely to have come across an account of Jaiden Rodriguez, the boy who was banned from the Vanguard School, a public charter school, because of the Gadsden flag "Don't Tread on Me" patch emblazoned on his backpack. All those media outlets carried stories on the incident, which was both newsworthy and infuriating.

The story rocketed to attention after Jaiden's mother challenged her son's punishment. She was told by the school's director that the Gadsden flag, with its famous image of a coiled rattlesnake, was prohibited "due to its origins with slavery and slave trade," which made it "disruptive to the classroom environment."

In fact, the Gadsden flag doesn't celebrate slavery. It was born during the American Revolution and was an emblem of the colonies' resistance to British tyranny. The flag was designed in 1775 by Christopher Gadsden, a representative from South Carolina to the Continental Congress who was a brigadier general during the war. He provided it to Commodore Esek Hopkins, the commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy, who flew it from the mainmast of his flagship, the USS Alfred. The emblem became an instant classic. Benjamin Franklin described the rattlesnake as "an emblem of vigilance," and adapted his own version, in which the snake was severed into 13 segments with the slogan: "Join, or Die."

A seaman aboard a guided missile cruiser raises the Navy Jack with its motto "Don't Tread On Me" at morning colors on Sept. 11, 2002, the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. |

The Gadsden flag has been an American icon for nearly 2½ centuries. In 1975, a very similar image — it depicted a snake extended on a field of 13 red and white stripes, above the motto "Don't Tread On Me" — was revived as the official Navy Jack and flown by every commissioned naval vessel during the Bicentennial year. It was later revived again after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The flag has been honored on a 6¢ US postage stamp, issued July 4, 1968.

So when Jaiden and his mother were told by school officials that the flag patch on his backpack stood for slavery, the pushback was widespread and fervent. Within days, Colorado's Democratic Governor Jared Polis had weighed in to set school officials straight. "The Gadsden flag is a proud symbol of the American revolution," he tweeted,

and an iconic warning to Britain or any government not to violate the liberties of Americans. It appears on popular American medallions and challenge coins through today and Ben Franklin also adopted it to symbolize the union of the 13 colonies. It's a great teaching moment for a history lesson!

It is true that the flag has over the years sometimes been appropriated by groups with their own political agenda, from antitax Tea Party activists to LGBT self-defense advocates. Some Trump supporters carried the Gadsden flag into the US Capitol during the mob action on Jan. 6, 2021. The flag is also available as a specialty license plate in a dozen states, and a bill introduced in Iowa would make that state the 13th.

Eventually, the Vanguard School reversed its punishment. It sent Jaiden's family a letter acknowledging "the historical significance of the Gadsden flag and its place in history," promising its "support of these American principles" and permitting the 12-year-old to return to class. No doubt the rebuke from the state's governor helped school administrators see the light, along with a detailed letter from lawyers at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, who explained that under well-established First Amendment jurisprudence, Jaiden's patch may not be censored.

As mentioned, this story got a lot of media attention, but only in certain quarters of the media. When I checked to find out how "mainstream" news outlets covered the incident, I mostly found — nothing. According to their own embedded search functions, there was nothing in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Globe, NPR, or the Los Angeles Times. Nothing in The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Oregonian, MSNBC, or The Guardian. I double-checked at the Nexis media database, with the same results.

I don't suggest there is anything nefarious about the failure of so many media organizations to report on a story that generated so much interest. I am suggesting that, for the most part, it's a mistake to believe that there is such a thing as "mainstream" American news media. There are news media that lean left and news media that lean right, and what one camp regards as newsworthy the other camp may not even notice — and vice versa. To one kind of journalist, a kid being drummed out of class because of a "Don't Tread On Me" patch on his backpack is emblematic of the ideological closed-mindedness that has taken root in numerous public schools and it illuminates the cultural clashes over the meaning of American history. To another kind of journalist, it barely registers — certainly not the way it would register if a student were to get in trouble for sporting a "Black Lives Matter" patch or a rainbow flag.

What is true in other areas of life is true of newsrooms: Once a consensus takes hold, it tends to reinforce itself and to downplay whatever undermines that consensus. When a common view is prevalent, it shapes not only how a story is covered but whether it gets covered in the first place. To some extent that was always the case, but it is much worse today, when journalism is as polarized as the rest of society and newspapers depend for more and more of their revenue on subscribers willing to pay for coverage they like. Reporters, editors, and publishers are now in the business of providing content to like-minded people. Stories their subscribers don't care about — or don't wish to know about — are stories that don't get published.

For all the talk of "diversity" in media circles, what most news organizations provide is uniformity: conservative uniformity in those that tilt right, progressive uniformity in the larger number that tilt left. The only way to be informed is to keep up with news from both sides. When all your information comes from people who agree with each other, you never know what you're missing.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Goons, gas stations, and the Garden State

I knew that New Jersey was the last remaining state to outlaw self-service gas stations. I knew that until very recently it shared that ignominious distinction with Oregon. I even knew that the official — and patently false — reason for not allowing customers to pump their own gas was to prevent a fire hazard.

It is obvious that New Jersey's prohibition on letting drivers man the pump is intended to boost the economic interests of someone other than drivers. The likeliest culprit is gas station owners who crave the excess profit. But why, I often wondered, didn't a more entrepreneurial filling station owner come along to provide motorists with another — cheaper — choice?

The answer, writes Jon Miltimore of the Foundation for Economic Education in a new essay, is that someone did — until the goons put him out of business with help from the Legislature.

The renegade's name was Irving Reingold. In the late 1940s, he came up with a way to give customers a bargain: He opened a 24-pump gas station on Route 17 in Hackensack, offering gas at about 3 cents a gallon less than the market price — on the condition that drivers fill their own tanks.

Reingold's business boomed. His customers lined up for blocks in order to pump their own gas. "His competition was less thrilled," Miltimore recounts. "They decided to stop him — by shooting up his gas station." Reingold responded by installing bulletproof glass. So his competitors turned to something deadlier than bullets: government.

The New Jersey Gasoline Retailers Association lobbied state lawmakers in Trenton to pass a measure banning self-serve gas pumps on the pretext that it wasn't safe. The lobbyists persuaded legislators that it was in their interest to go along with the scam. In short order, Reingold was driven out of business.

There is a popular delusion that political leaders and bureaucrats aren't motivated by personal gain and can be trusted to act in the public interest. Again and again, we are told that the solution to some crisis, real or imaginary, is for government to pass a law or impose new regulations. But just as those clamoring for the change often have ulterior motives, government officials usually do too.

"Politicians in New Jersey couldn't very well admit they were serving their own interests when they decided to play ball with the Gasoline Retailers Association," writes Miltimore. "They had to convince people they were protecting [them] from the chaos that would ensue if consumers were allowed to pump their own gasoline at a lower price." That was ludicrous in 1949. It is positively deranged today. Yet New Jersey's absurd ban on pumping gas persists, a testament to staying power of idiotic government rules and the special interests that defend them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "In the 8th District, it makes no difference who wins," Sept. 3, 1998:

The new congressman from Cambridge and Boston will be a freshman in a body where seniority is consequential. He or she will be a Democrat in a Congress with a Republican majority — and if the tea-leaf diviners are right, the 106th Congress will be even more Republican than the 105th.

It will be hard enough to accomplish anything as a freshman Democrat. As a freshman Democrat from Massachusetts, Joe Kennedy's successor is assured of having no clout. The Bay State, after all, is one of only four states with an all-Democratic congressional delegation and the only one of significance in terms of industry or population. There is a price to be paid for shunning the nation's dominant political party. The price for Massachusetts is a notable lack of influence in Washington.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Well, I would like to make another trip," he said, jumping to his feet; "but I really don't know when I'll have the time. There's just so much to do right here." — Norman Juster, The Phantom Tollbooth (1961)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.