EVER SINCE Roe v. Wade was overruled last year, abortion politics have decisively favored Democrats.

In every state where abortion rights have been on the ballot, including Republican strongholds like Kentucky and Kansas, voters have defeated the anti-abortion position. The most recent victory for supporters of abortion rights came earlier this month in Ohio, where voters handily defeated a ballot question that didn't even mention abortion — it concerned the level of support required to amend the state's constitution — but was understood to be backed by abortion opponents. In last fall's midterm elections, the widely predicted "red wave" never materialized, in significant part because the abortion issue hurt Republicans. Voters even flipped control of the Wisconsin Supreme Court from right to left, electing a judge who had campaigned on a platform of explicit support for abortion rights.

This string of losses was surely not what Republicans were hoping for in the wake of Roe's reversal in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, though it is what some in the pro-life camp, your humble correspondent included, had predicted. "The thought of overturning Roe fills Democrats with alarm, but it shouldn't," I remarked in a 2018 column. "Return abortion to the democratic arena, and Democrats might be surprised at how much they stand to gain." Similarly, more than a year before Dobbs was decided, I explained why "a post-Roe world is apt to be less congenial to the GOP that craves it, and not nearly as challenging to the Democratic Party that doesn't."

Many Republicans are now struggling to find their footing on the abortion issue, navigating between the strong and sincere opposition to virtually all abortions among the party's base while trying not to write off general election voters who support moderate abortion rights. So it stands to reason that abortion was the most discussed issue during the Republican presidential candidates' debate in Milwaukee last week. It also stands to reason that several of the candidates were at pains to remind viewers of just how extreme the Democratic position on abortion is.

That extremism is commonly ignored, downplayed, or denied by the mainstream media. But there is no question that within the ranks of the Democratic Party and its allies, support for the right to legally end a pregnancy is close to absolute — "abortion on demand and without apology," as the signs at countless abortion-rights rallies have often proclaimed.

In 2004, the Democratic Party platform famously declared that "abortion should be safe, legal, and rare." As a candidate for president four years later, then-Senator Hillary Clinton underscored that formulation, adding: "By rare, I mean rare."

But "rare" has since been edited out of the party's abortion plank. Today, open praise for abortion — not merely the right to choose, but abortion itself — has become common in activist circles. "We're not just pro-choice," tweeted the Women's March last fall. "We are proudly, unapologetically pro-abortion." The Massachusetts chapter of Planned Parenthood urges supporters "to go beyond choice language when we're talking about abortion." Use of the term "pro-choice" is "hurtful to people who've had abortions," it argues, because it implies that abortion isn't objectively a good thing. When Senator Ed Markey attended President Biden's State of the Union address this year, he wore a large pro-abortion pin on his suit jacket. It spelled out the word "ABORTION" in large gold letters, with the first "O" surrounding a heart.

Democrats support legislation to "codify Roe v. Wade." That's code for "abortion with no legal limitations." |

Several times during the Republican debate, mention was made of the fact that Democrats want "to allow abortion all the way up to the moment of birth." That was Florida Governor Ron Desantis's wording, but the same basic point was made by Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina and former Arkansas governor Asa Hutchinson. It was also made by one of the debate moderators, Fox News host Martha MacCallum, who observed that there are "about five" states "that allow abortion up until the time of birth."

That is admittedly a provocative way to characterize the Democrats' extreme abortion posture, and several on the left rushed to refute it. "No one supports abortion up until birth," former White House press secretary (and current MSNBC talking head) Jen Psaki tweeted indignantly. The reliably liberal FactCheck.org called the claim "misleading," while The New York Times accused the GOP candidates of "falsely" stating the Democratic position.

But there is nothing false about it. The Democratic Party categorically affirms an unlimited right to abortion. "We believe unequivocally . . . that every woman should be able to access high-quality reproductive health care services, including safe and legal abortion," the 2020 Democratic platform states. It calls explicitly for the abolition of every existing legal limitation on abortion ("repeal the Title X domestic gag rule . . . restore federal funding for Planned Parenthood . . . fight to overturn federal and state laws that create barriers to reproductive health and rights . . . repeal the Hyde Amendment . . . protect and codify the right to reproductive freedom"). There is not a single legal limitation on abortion that most Democratic Party leaders and activists would accept.

The proposed Women's Health Protection Act, the legislation to "codify Roe" backed by most congressional Democrats, would establish a nationwide right to abortion, overriding all state laws banning abortion at any stage. The bill provides that abortion would be lawful even after fetal viability, so long as a "health care provider" — which need not be a doctor — determines that ending the pregnancy is necessary to preserve the "life or health" of the mother. That was the standard created under Roe v. Wade. But in the companion case of Doe v. Bolton decided the same day, the justices ruled that "health" could refer to any consideration — "physical, emotional, psychological, familial." Under such a limitless definition, the exception swallowed the rule, making abortion lawful at any stage of pregnancy.

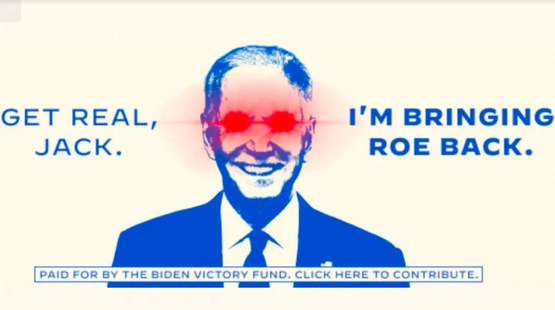

No, Democrats do not say in so many words that they endorse abortion through all nine months of pregnancy. But just try to find a progressive leader or Democratic candidate who will specify the legal limits on abortion they do endorse. Their refusal to accept any restriction on "choice," no matter how measured, is the counterpart to hardliners in the GOP who would make it virtually impossible to terminate any pregnancy. When Biden advertises that he is "bringing Roe back," that is what he means.

Most voters are not in either extremist camp. I'm pro-life, but I acknowledge that Democrats have good reason to point out just how far some Republicans will go to prevent any and all abortions. It makes just as much sense for Republicans to point out how far Democrats will go to protect any and all abortions.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

When New York had more migrants, it had no migrant crisis

In 1907, 1.3 million immigrants came to the United States. The vast majority of them arrived in New York City, pouring through the major entry point of Ellis Island. For all intents and purposes, the concept of "illegal immigration" didn't exist then — with few limitations, any would-be American who could get to the United States could enter the country. (The one significant exception was the racist Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred immigrants from China.)

In its heyday, an average of 5,000 migrants surged into New York daily through Ellis Island. Some days, of course, were busier than average. On April 17, 1907, a whopping 11,747 migrants disembarked in New York harbor. Of the million or more foreigners immigrating to the United States each year, roughly one-fourth settled in the city or in nearby New Jersey.

Like the country as a whole, New York was poorer then, with far fewer government resources and social services. The air, water, and streets were dirtier, health care was more primitive, and neighborhoods were far more congested. According to the Library of Congress, Manhattan's Lower East Side "was packed with more than 700 people per acre, making it the most crowded neighborhood on the planet." And yet, even as thousands of newcomers entered daily, it never occurred to New York mayors of that era to plead with Washington to declare a state of emergency or to beg — as Mayor Eric Adams did this month — for "federal funds to be allocated quickly to help address the urgent challenges we face."

How was it that New York City could cope with 5,000 people streaming through its "Golden Door" every day in first decade of the 20th century, yet is driven to the breaking point by 800 to 1,000 daily arrivals in the third decade of the 21st century? New York City's budget in 1907 was $130.4 million; this year's outlays, at $107 billion, represent nearly a thousandfold increase. Yet New York in 1907 was open to the river of migrants coursing over its borders, while New York in 2023 is pleading with the new arrivals to go somewhere else. Why?

The answer is not complicated. It has far less to do with the number of Latin American migrants crossing the chaotic southern border and everything to do with what those migrants have been told to expect when they get here: free housing. In a nutshell, New York City guarantees shelter at no charge to anyone who needs it. Under the terms of the city's "Callahan decree" of 1981, New York agreed to provide housing and board to all "destitute and homeless" persons who seek assistance. That entitlement, fiercely defended by activist groups and upheld in repeated court judgments, has been a fiscal calamity for New York, obligating the city to spend ever more money on sheltering the homeless while ensuring that the influx of people in need of shelter persists. Massachusetts likewise has a right-to-shelter policy and, not coincidentally, also finds itself in a crisis as it tries to provide housing for migrants.

On a single day in 1907, nearly 12,000 immigrants entered New York City at Ellis Island. The city did not declare a state of emergency. |

Reporting recently in City Journal, Daniel Di Martino — himself an immigrant from Venezuela and a PhD candidate in economics at Columbia University — sought to better understand New York's "self-inflicted migrant crisis" by interviewing numerous individuals at Manhattan's Roosevelt Hotel, a once-glamorous haven for travelers that has been turned into a temporary shelter for homeless foreigners.

Writes Di Martino: "I asked every migrant, 'Why New York City?' Their responses varied but had a common thread: In New York City, they could get housing at no cost." The city's right-to-shelter policy is a powerful magnet, encouraging people who would otherwise have made different plans to rely on the government for housing. "While compassionate in intent, the policy is unsustainable. Today, about 60,000 migrants reside in city shelters and temporary housing, outnumbering New Yorkers in those facilities." Human beings respond to incentives and New York has created an incentive for immigrants to do something they wouldn't have done a century ago — relocate to America with no way to provide for themselves. The once-ironclad rule against becoming a "public charge" has been largely nullified. The result is the state of emergency in which the city finds itself.

"I feel compassion for the shelter residents," Di Martino says. "They have suffered immensely, often through no fault of their own. The terrible situations from which they are fleeing are the responsibility of the authoritarian regimes and corrupt governments of their home countries. But on the altar of unlimited compassion, we risk sacrificing the very prosperity these migrants hope to achieve. The United States — much less New York City — cannot guarantee shelter for all the world's oppressed."

The solution to the current migrant crisis is not to build a wall on the border, or lock asylum-seekers in detention centers, or to clamp down on the number of people permitted to come to America. It is to restore the understanding that existed in the 19th century and the turn of the 20th century, when virtually anyone who wanted to become an American could do so — so long as they didn't become a public charge.

A century and a half ago, there was no government funded social-safety net to speak of in New York or anywhere else in America. While there has always been an elaborate network of private aid societies, immigrants had no access to food stamps, Medicaid, unemployment benefits, or guaranteed housing at taxpayer expense. The millions of men, women, and children who flowed into the city and the country over the years did not always thrive; many struggled painfully to put down roots in their new country. A sizable minority even ended up returning to their home countries. Yet as harsh as the system was, it facilitated the greatest and most successful peaceful transfer of population in modern times, elevating America to the ranks of an economic and cultural superpower and establishing what was until recently the largest and richest middle class on earth.

I have always endorsed an open-door policy on immigration — peaceful individuals from any country should be free to move to the United States without impediment other than background vetting for security. But open immigration cannot coexist with lavish welfare. Newcomers must know that it is their responsibility to provide for themselves or to seek help privately, and that they cannot expect to live off government largesse. That was the understanding that prevailed for decades, and the lives of millions were improved in the process. What worked for the migrants of 1900 would work for the migrants of today, if only policymakers had the wisdom and courage to change direction.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Yandle belongs in prison for life," Sept. 3, 1998:

Life without parole is a terrible punishment. It is meant to be. For stealing a man's life, how could the law exact a penalty that wasn't terrible? The price for Joe Reppucci's life was decided fairly and imposed after due process of law. No one had the right in 1995 to cheapen that price — not Weld, not the Governor's Council, not "60 Minutes," not The Boston Globe, not the Vietnam Veterans of America.

It matters not that Yandle may no longer pose a threat to society. It matters not that he wants to counsel at-risk kids. It matters not whether he did or didn't earn two Purple Hearts. It matters not that he now expresses shame for his crimes. It matters only that he was guilty as charged.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: 'Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.'" — Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., I Have A Dream (Aug. 28, 1963)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.