ON MAY 19, 1856 — 167 years ago this week — Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, a gifted orator and the US Senate's foremost opponent of slavery, rose to deliver a speech on the events unfolding in Kansas. The territory was embroiled in violence as pro- and anti-slavery forces battled over whether Kansas would join the Union as a slave state or a free state. Sumner's speech, which he delivered over two days, was a passionate denunciation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the federal law that left it up to the residents of each new state to decide whether human bondage would be allowed within their borders.

"Sumner's speech had drawn an unusually large audience," writes the historian David Herbert Donald in Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War, his enthralling biography of the Bay State senator. The galleries were filled to capacity, the doorways were crowded with spectators, and "virtually every member of the Senate was in his seat as Sumner began."

At first Sumner focused on the disastrous fallout of the 1854 law. But then his remarks turned personal. He poured scorn on the lawmakers who were responsible for this "Crime against Kansas" — "senators who raised themselves to eminence on this floor in championship of human wrong." In particular he excoriated Democrats Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina, the chief sponsors of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He insulted Douglas as a "noisome, squat, and nameless animal" who "fills the Senate with . . . offensive odor." As for Butler, Sumner sneered, "he believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage," but he consorts with "a mistress . . . who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight." That mistress, he said, is "the harlot, Slavery."

Among Northern abolitionists, reaction to the speech was ardent. The New York Tribune gushed that "Mr. Sumner has added a cubit to his stature." Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called Sumner's oration "the greatest voice on the greatest subject that has been uttered."

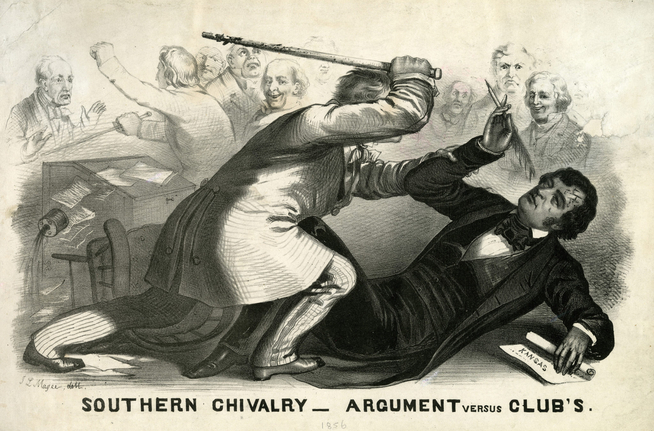

A political caricature depicted the caning of Senator Sumner, shown with a pen in one hand and a copy of his speech in the other, as an illustration of 'Southern chivalry.' |

But the Massachusetts senator's words infuriated Southerners — none more than Preston Brooks, a South Carolina congressman and Butler's cousin. On May 22, after the Senate had adjourned for the day, Brooks entered the chamber carrying a gold-headed walking stick. He walked up to Sumner, who was seated alone at his desk working on correspondence. "With cool self-possession and formal politeness," writes Donald in his biography, he addressed the senator in a low voice.

"Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully," Brooks said. "It is a libel on South Carolina and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine." Then he began striking Sumner with the metallic head of his cane, raining down repeated blows. Sumner, stunned by the attack and blinded by the blood running into his eyes, staggered to his feet. Brooks kept beating him, striking with such ferocity that the cane snapped. Again and again he bashed Sumner, not stopping even when the senator lost consciousness. "Brooks reached out and with one hand held Sumner up by the lapel of his coat while he continued to strike him with the other," recounts Donald. "By this time the cane had shivered to pieces."

The beating lasted no more than a minute, but its effect on American history would be long and terrible. Sumner was taken from the Senate drenched in blood. So devastating were his injuries that it would be three years before he recovered enough to return to his seat. For the rest of his life, the brain injuries he had suffered would cause severe chronic pain and what today would be called post-traumatic stress disorder.

The damage to the nation's civic health was, if anything, even more traumatic. The attack confirmed that politics in America had grown polarized beyond salvation. Sumner became even more of a hero to abolitionists. His ordeal, which galvanized antislavery opinion, was powerfully symbolic: If one of the most influential white men in the country could be beaten senseless in the US Capitol, what recourse was there for an enslaved field hand brutalized by a cruel master?

Across the North, in cities large and small, public rallies were held to protest Brooks's assault. Hundreds of thousands of copies of Sumner's speech were distributed. Support for the new Republican Party surged.

Throughout the South, by contrast, Brooks was lionized. The Richmond Enquirer hailed his attack on Sumner as "good in conception, better in execution, and best of all in consequences." Another Virginia newspaper was chagrined only because Brooks had beaten the Massachusetts abolitionist with a cane instead of using "a horsewhip or a cowhide upon his slanderous back." Hundreds of admirers sent new walking sticks to the congressman; one presented by the city of Charleston was inscribed: "Hit him again!" When the House of Representatives voted to censure Brooks, he promptly resigned, returned to South Carolina, and was reelected to his seat in a landslide.

What happened to Sumner convinced many Americans that the chasm separating North and South could never be resolved peacefully. The nation's two halves "no longer spoke the same language, shared the same moral code, or obeyed the same law," wrote Donald. More and more people "began to wonder how the Union could longer endure."

Nearly five years after the caning of Sumner, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as president. "We must not be enemies," he pleaded in his inaugural address. "Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection." But those bonds had long since been broken. A murderous Civil War was the result.

Americans in our time, too, seem to have forgotten how to reason together, how to disagree without despising, how to prevent the fabric of society from ripping apart at the seams. Discord and distrust are at crisis levels. For those with clashing world views and partisan loyalties, finding common ground has grown nearly impossible. Divergent opinions are treated as deadly threats, to be resisted not with courtesy and a willingness to hear each other out, but with hostility and slander. We too have witnessed shocking scenes of mayhem and violence in the Capitol Building. The America Sumner and Brooks inhabited couldn't pull itself back from the brink. Can we?

*

Islamic Jihad and the T-word

Israel and Palestinian Islamic Jihad agreed over the weekend to a cease-fire brokered by Egypt, bringing a halt to five days of fighting during which 35 people were killed and more than 200 injured. Between May 9 and May 13, Islamic Jihad fired nearly 1,500 rockets and mortars from Gaza into Israel. Fortunately, most of those that directly threatened Israeli population centers were intercepted by the Iron Dome missile defense system, or the death toll would have been much higher. According to the Jerusalem Post, 20 percent of Islamic Jihad rockets fell short and landed in Gaza, killing three Palestinians.

Though it is funded and supplied by Iran, Islamic Jihad is based in Gaza, which has long been ruled by Hamas. (Israel's occupation of Gaza ended 18 years ago.) Both organizations are explicitly committed to the destruction of the Jewish state and its replacement with an Islamist regime, but the much larger Hamas steered clear of the latest violence; as The Washington Post noted, it is still recovering from previous confrontations with Israel.

In the 42 years since it was founded, Islamic Jihad (also referred to as PIJ) has compiled a long and bloody record of terrorist atrocities. "A key component of PIJ's doctrine is the belief in violent jihad in order to liberate Palestine," explains the Counter-Extremism Project, a nonpartisan international research organization. "PIJ has been responsible for numerous suicide attacks and hundreds of rockets against Israeli civilian centers" and "it is highly unlikely the group will ever renounce terrorism, which has become an integral part of PIJ's raison d'etre."

Among the innumerable innocents murdered by Islamic Jihad over the years was Alisa Flatow, a young American I had the pleasure of meeting when she was a student at Brandeis University. In December 1994, Alisa invited me to speak at a campus event she was organizing and when I arrived she greeted me with friendly enthusiasm. A few weeks later, she flew to Israel to spend a semester studying abroad. On April 9, 1995, Alisa took a day off to visit Kfar Darom, a town in the Gaza near the Mediterranean shore. She never made it back. An Islamic Jihad suicide bomber, Khaled Mohammed Khatib, drove a car loaded with explosives into the bus on which Alisa was riding; she was one of eight people killed.

The single most salient fact about Islamic Jihad is its fanatical commitment to terrorism. It has been designated a terrorist organization by the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

So why, when mainstream news organizations refer to Islamic Jihad, do they sedulously avoid using the word "terrorist" to describe it? In their coverage of the fighting last week, leading media outlets daintily labeled the organization "militant." So tepid a word doesn't convey the evil reality of those who not only seek to murder innocent Israeli civilians, but also site their rocket launchers and command posts in the midst of Palestinian civilians, thereby turning them into human shields.

Some examples:

- The New York Times: "Fierce cross-border fighting resumed on Friday between Israel and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad militant group in Gaza."

- The Washington Post: "What is Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the militant group Israel is targeting in Gaza?"

- NPR: "Israel launched targeted airstrikes in densely populated areas of the Gaza Strip early Tuesday, killing three senior commanders of the Islamic Jihad militant group."

- The Guardian: "Fighting between Israel and militant groups in the blockaded Gaza Strip has intensified for the third day."

- CNN: "Palestinian militants launched rockets towards Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Israeli settlements."

In other contexts, these publications have no problem with the term "terrorist." Just this month, The Guardian reported a story out of Brussels under the headline "Belgian police arrest seven people over terror attack plot," NPR referred to "the use of data mining to track potential terrorists," The Post discussed "conflicts over the publication of images of death stemming from wars, terrorist attacks, or shootings," and The Times observed that an American embassy "was the site of one of Tunisia's last terrorist attacks."

But Islamic Jihad, which blows up buses carrying American college students and fires rockets into residential neighborhoods, is merely "militant." Really?

The influential Associated Press stylebook decreed last summer that "the use of the word 'terrorism' or 'terrorist' is to be attributed to authorities with respect to specific actions" — that is, only to be used when quoting officials — and may otherwise be invoked only "when talking about historical events widely acknowledged as terrorist actions."

That provoked a tart comment from Scott Johnson at the venerable PowerLine blog: "You don't want to be too judgmental. You don't want to pick a side, even when it's your own. You want to adopt an abstruse terminology that obscures who is who, what is what, and what is happening."

Alas, this is not a new phenomenon.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, the Reuters news service refused to use the words "terror" and "terrorists" (except in quotations) when referring to the horrors committed by Al Qaeda in New York City and Washington. "We all know that one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter," intoned Stephen Jukes, the chief of global news at Reuters. When David Westin, the president of ABC News, was asked at the Columbia Journalism School whether the Pentagon was a legitimate target for the 9/11 hijackers, he responded: "I actually have no opinion on that."

One veteran journalist was scandalized by those attitudes. To Bob Zelnick, who for decades had been an ABC News correspondent (and later taught at Boston University's journalism school), such obsessive neutrality in the face of terrorist atrocities reflected the moral confusion that arrogance can lead to. "If the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were not acts of evil criminality," he asked, "then is anything criminal?" If "killing innocent civilians for political purposes is not terrorism," why not ban the word "murder" when reporting on the premeditated killing of an individual?

Palestinian Islamic Jihad — like Hamas, Al Qaeda, and ISIS — is a terrorist group. "Killing innocent civilians for political purposes" is its mission. The unwillingness of some news organizations to say so plainly doesn't make Islamic Jihad less monstrous. It only makes the news media less reliable.

*

'Harbor seeds of goodness'

E.B. White: 'Wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day.' |

After such disheartening reflections, you deserve to read something a bit more uplifting. So allow me to share with you a lovely letter written by E. B. White, the 20th-century American author who wrote the beloved children's classics Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little.

In March 1973, White received a letter from a reader who was depressed about the prospects for humanity. In his beautiful response, which is reprinted in Letters of E. B. White, he sought to raise his correspondent's spirits.

"Dear Mr. Nadeau," he began.

As long as there is one upright man, as long as there is one compassionate woman, the contagion may spread and the scene is not desolate. Hope is the thing that is left to us, in a bad time. I shall get up Sunday morning and wind the clock, as a contribution to order and steadfastness.

Sailors have an expression about the weather: they say, the weather is a great bluffer. I guess the same is true of our human society — things can look dark, then a break shows in the clouds, and all is changed, sometimes rather suddenly. It is quite obvious that the human race has made a queer mess of life on this planet. But as a people we probably harbor seeds of goodness that have lain for a long time waiting to sprout when the conditions are right. Man's curiosity, his relentlessness, his inventiveness, his ingenuity have led him into deep trouble. We can only hope that these same traits will enable him to claw his way out.

Hang on to your hat. Hang on to your hope. And wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day.

Sincerely,

E. B. White

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "What did India do wrong?," May 19, 1998:

If harsh sanctions are in order when the world's largest democracy beefs up its nuclear arsenal, why not when the world's largest dictatorship does so?

India's five nuclear explosions last week were severely denounced by President Clinton, who compared them to "the very worst events of the 20th century" and announced a variety of economic punishments. Yet Clinton has never seen fit to chastise China, which over the years has conducted not five but 45 nuclear tests, and which has not merely tested nuclear missiles but deployed them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.