Bush was no Putin, and Iraq was no Ukraine

An inadvertent slip of the tongue by George W. Bush during a speech last week triggered a spasm of what the late great Charles Krauthammer, a psychiatrist by training, dubbed Bush Derangement Syndrome. That disorder he defined as an "acute onset of paranoia in otherwise normal people in reaction to the policies, the presidency, nay, the very existence of George W. Bush."

The slip occurred as Bush spoke at his presidential center in Dallas. He was condemning Vladimir Putin for manipulating elections and persecuting political critics, and observed that when autocrats are not bound by the constraints of democracy at home, they are apt to become dangerously aggressive abroad.

"Russian elections are rigged, political opponents are imprisoned or otherwise eliminated from participating in the electoral process," Bush said. "The result is an absence of checks and balances in Russia, and the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq — I mean, of Ukraine."

As the audience chuckled at the minor gaffe, Bush added, "75" — a self-deprecating reference to his age. But the BDS-afflicted seized on the flub to slam the 43rd president for what they continue to deplore as his villainous war in Iraq.

"I'm not laughing and I am guessing nor are the families of the thousands of American troops and the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who died in that war," tweeted MSNBC host Mehdi Hasan who called Bush's stumble "one of the biggest Freudian slips of all time." Ohio Democrat Nina Turner, a hard-left progressive, declared that Bush "just admitted to being a war criminal of the likes of Vladimir Putin." From the other side of the political spectrum, former Representative Justin Amash, a Libertarian, suggested that Bush ought to "just steer clear of giving any speech about one man launching a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion."

There was plenty more where that came from, but the general indictment is by now quite familiar: The war against Saddam Hussein's Iraq was an outrage, it was based on a deliberate lie about nonexistent weapons of mass destruction, it led to the ghastly consequences and widespread slaughter that Democrats predicted, and all of it was the fault of Bush and the bloody-minded warhawks who served under him.

It's a popular narrative. It's also false.

Here's the truth: The invasion of Iraq was justified, and the vast majority of Americans who supported it — including most of the nation's leading Democrats — were right to do so.

Which leading Democrats? Joe Biden, for one.

When he ran for president in 2020, Biden repeatedly insisted that he had opposed the Iraq war "from the very moment" it started. During one Democratic debate in Des Moines, he claimed that the Bush administration had promised "they were not going to go to war," but that he knew better and kept "making the case that it was a big, big mistake."

In reality, Biden was all for going to war — as long as that was a popular stance.

In the fall of 2001, when he was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden was among those who argued that war with Iraq was inevitable and that the United States should "tighten the noose" around Saddam's neck and depose him. In a speech in 2002, he said it was imperative "to end the regime one way or another" and argued that Saddam's overthrow was essential to winning the war on terror. Later that year, when he voted for the resolution authorizing military action in Iraq, Biden took to the Senate floor to explain why "Saddam must be dislodged from power." In February 2003, he reiterated his support: "Let everyone here be absolutely clear," he told an audience in his home state of Delaware, "I supported the resolution to go to war. I am NOT opposed to war to remove weapons of mass destruction from Iraq. I am NOT opposed to war to remove Saddam." The all-caps are in Biden's official transcript of the speech.

The Iraq Liberation Act, signed by President Clinton in 1998, made regime change in Iraq an explicit policy of the United States. |

As the US attack got underway in March, Biden strongly endorsed the operation. "I support the president. I support the troops," he said on CNN. Four months later, his resolve hadn't weakened. "Some in my own party have said that it was a mistake to go to Iraq in the first place and believe that it's not worth the cost," Biden told the Brookings Institution in July 2003. "But the cost of not acting against Saddam, I think, would have been much greater."

However inconvenient it later became for the Bush-haters to acknowledge the fact, Bush was by no stretch of the imagination acting unilaterally when he committed the United States to war in Iraq. He acted by the authority of a decidedly bipartisan Congress — the war resolution had the support of most Senate Democrats, including not only Biden, but also John Kerry, Hillary Clinton, Diane Feinstein, Harry Reid, and Charles Schumer.

Nor did Bush act against the wishes of the American people.

In February and March of 2003, polls taken by Gallup, Pew, and multiple news organizations showed lopsided public backing for the war. There were some notable officials, such as Barack Obama and Bernie Sanders, who opposed the war. But most Republicans and Democrats had long understood that Saddam was a deadly and destabilizing menace who ought to be ejected from power. In October 1998, more than two years before Bush was elected president, President Bill Clinton signed the Iraq Liberation Act, which made it an explicit goal of US policy "to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq."

In blunt terms, Clinton reviewed the history that had led to that point:

Remember, as a condition of the cease-fire after the Gulf War, the United Nations demanded and Saddam Hussein agreed to declare within 15 days — this is way back in 1991 — within 15 days his nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons and the missiles to deliver them, to make a total declaration. That's what he promised to do.

The United Nations set up a special commission of highly trained international experts called UNSCOM, to make sure that Iraq made good on that commitment. We had every good reason to insist that Iraq disarm. Saddam had built up a terrible arsenal, and he had used it not once, but many times. In a decade-long war with Iran, he used chemical weapons against combatants, against civilians, against a foreign adversary, and even against his own people. And during the Gulf War, Saddam launched Scuds against Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Bahrain.

Now, instead of playing by the very rules he agreed to at the end of the Gulf War, Saddam has spent the better part of the past decade trying to cheat on this solemn commitment. . . .

Despite Iraq's deceptions, UNSCOM has nevertheless done a remarkable job. Its inspectors — the eyes and ears of the civilized world — have uncovered and destroyed more weapons of mass destruction capacity than was destroyed during the Gulf War.

This includes nearly 40,000 chemical weapons, more than 100,000 gallons of chemical weapons agents, 48 operational missiles, 30 warheads specifically fitted for chemical and biological weapons, and a massive biological weapons facility at Al Hakam equipped to produce anthrax and other deadly agents.

Then Clinton laid out what was at stake going forward — and why US inaction was not an option:

Now, let's imagine the future. What if he fails to comply, and we fail to act, or we take some ambiguous third route which gives him yet more opportunities to develop this program of weapons of mass destruction and continue to press for the release of the sanctions and continue to ignore the solemn commitments that he made?

Well, he will conclude that the international community has lost its will. He will then conclude that he can go right on and do more to rebuild an arsenal of devastating destruction.

And some day, some way, I guarantee you, he'll use the arsenal. . . .

But the bipartisan consensus on Iraq that began well before Bush entered the White House and that strongly favored the invasion in March 2003 became a casualty of the war. Once it became clear that Hussein had not recreated the stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons that had been a major justification for the war, unity gave way to recrimination. It didn't matter that virtually everyone — Republicans and Democrats, UN inspectors and CIA analysts, European allies, even Saddam's own military officers — had been sure the caches of WMD would be found. Nor did it matter that Saddam had previously used WMD to exterminate thousands of victims. The temptation to spin an intelligence failure as a deliberate piece of deception was politically irresistible.

Not everyone is motivated by politics, however. Among those who maintained strongly that the Bush administration had acted in good faith were the very weapons inspectors who confirmed that Saddam's supposedly vast stockpiles of chemical and biological agents couldn't be found.

David Kay, the chief US weapons investigator in Iraq, caused enormous consternation when he reported to Congress several months after Saddam was overthrown that his team had failed to find illegal weapons of mass destruction. "Clearly the intelligence that we went to war on was inaccurate," Kay told NBC's Tom Brokaw. But that didn't mean the White House had ginned up a phony threat, he said in response to Brokaw's question.

Brokaw: The president described Iraq as "a gathering danger." Was that an accurate description?

Kay: I think that's a very accurate description.

Kay noted that "Baghdad was actually becoming more dangerous in the last two years than even we realized." It was a point he reinforced in other interviews as well. Asked on NPR if Iraq had truly posed an imminent threat to its neighbors or the United States at the time of the invasion, Kay didn't hesitate: "Based on the intelligence that existed, I think it was reasonable to reach the conclusion that Iraq posed an imminent threat."

To be clear, Bush had not claimed to be acting in response to an imminent threat. Addressing a joint session of Congress in January 2003, he said:

Some have said we must not act until the threat is imminent. Since when have terrorists and tyrants announced their intentions, politely putting us on notice before they strike? If this threat is permitted to fully and suddenly emerge, all actions, all words, and all recriminations would come too late. Trusting in the sanity and restraint of Saddam Hussein is not a strategy, and it is not an option.

I strongly supported the Iraq war in 2003. I would have done so even if we had known in advance that Saddam had not re-assembled the "arsenal of devastating destruction" that Clinton had described. To my mind, the deadliest WMD in Iraq was Saddam himself. He was a monster who had committed ghastly crimes against humanity — invading neighboring countries, gassing Kurdish civilians by the thousands, engaging in torture on a terrifying scale, sponsoring international terrorism, and attempting to assassinate a US president.

And even that grim litany of crimes doesn't begin to hint at the sheer unbridled cruelty of Saddam's rule.

Horror in Saddam's Iraq took endless forms. In an interview in 2002, the BBC interviewed "Kamal," a former Iraqi torturer who had been captured and imprisoned in the Kurdish region that American forces protected with a no-fly zone. Kamal explained what Saddam's men were prepared to do to anyone deemed an opponent of the regime.

"If someone didn't break, they'd bring in the family," he said. "They'd bring the son in front of his parents, who were handcuffed or tied and they'd start with simple tortures such as cigarette burns. And then if his father didn't confess they'd start using more serious methods," such as slicing off one of the child's ears or amputating a limb. "They'd tell the father that they'd slaughter his son. They'd bring a bayonet out. And if he didn't confess, they'd kill the child."

Saddam's Iraq was a land of endless sadism. Amnesty International once listed some 30 different methods of torture regularly used in Iraq. They ranged from burning to rape to gouging out eyes. Far from going to great lengths to keep evidence of torture secret, Saddam's men tended to flaunt their crimes, leaving the broken bodies of victims in the street or returning them, mangled and mutilated, to their families. That blood-soaked record, no less than Saddam's violations of UN resolutions and attacks on other countries, justified international action to depose him.

VIDEO: Residents of Kurdistan, in the north of Iraq, expressed gratitude to the United States for defeating Saddam Hussein, who had inflicted so much death and horror on the Kurds. |

It only took a few weeks for the US-led invasion to overthrow Saddam, but then came the long and bloody insurgency, which the Bush administration proved woefully unprepared for. US commanders failed to secure the country or the vast quantities of conventional munitions stored around Iraq. Unwisely, the Iraqi Army was disbanded entirely, rather than purged of its Saddam loyalists and otherwise kept intact. As the anti-American insurgency worsened, what had initially seemed an easy victory turned into a grinding slog.

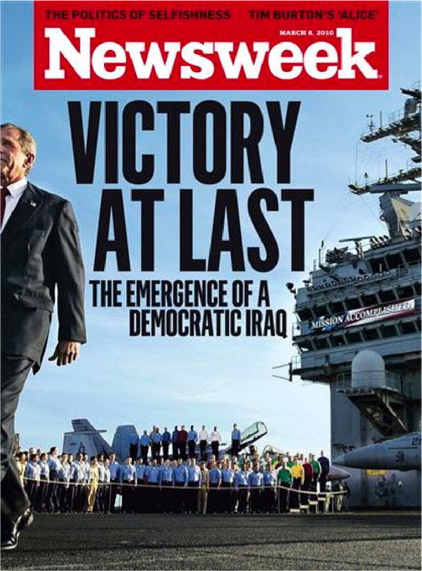

But in 2007 came Bush's "surge" and the course of the war shifted dramatically for the better. By the time Barack Obama took office, the insurgency was crippled, violence was down 90 percent, and Iraqis were being governed by politicians they had voted for. It was far from perfect, but "something that looks an awful lot like democracy is beginning to take hold in Iraq," reported Newsweek in early 2010. On its cover the magazine proclaimed: "Victory at Last."

Victory it was. And victory it would have remained, if America's new commander-in-chief hadn't been so insistent on pulling the plug.

"It's easy to forget that before Barack Obama's terrible decision to withdraw in 2011, the Iraq War had been won," wrote David French for National Review in 2019.

Saddam was gone, the follow-on insurgency had been wiped-out — reduced to a few hundred fighters scattered in a vast country — and American and Iraqi forces were masters of the battlefield. Joe Biden asserted that Americans would look at Iraq as "one of the great achievements of this administration." But Obama withdrew too soon. He squandered American gains, opened the door to unrestrained factionalism, and left the fragile Iraqi nation vulnerable to renewed jihadist assault.

Obama's determined disengagement wrecked what had so painstakingly been achieved. In the political vacuum that followed the US departure, the remnants of al Qaeda in Iraq reconstituted themselves as ISIS, a band of genocidal Islamists who turned much of Iraq and neighboring Syria into an abattoir, inspiring a wave of terror in Europe and unleashing an immense refugee crisis. Eventually Obama reversed course, putting American boots back on the ground in Iraq to preserve the country from collapse.

"More than 4,400 Americans died during Operation Iraqi Freedom, including men I served with and loved like brothers," wrote French.

They died in a just cause fighting enemies of this country — a regime and an insurgency that in different ways threatened vital American interests and actively sought to kill Americans and our allies. War is horrible, and the Iraq War is no exception to that rule. Civilian casualties were terrible and often intentionally inflicted by our enemies to destabilize the country and inflame sectarian divisions. But I truly believe the choice our nation faced was to fight Saddam then, on our terms, or later, when he had recovered more of his nation's strength and lethality. The United States is safer with him gone. It's just a terrible shame that for a time we chose to throw away a victory bought with the blood of brave men.

I agree. As in every war America ever fought, grievous mistakes were made in Iraq. But America's determination to end Saddam's reign of terror was a worthy one. An international coalition led by the United States, with broad Republican and Democratic backing, ended the reign of a genocidal tyrant. Joe Biden and most of his fellow Democrats were right to support the war that liberated Iraq, even if today they disavow all connection with it.

By the time George W. Bush left office, the war in Iraq was widely recognized as having finally been won. |

No, Bush's minor flub last week wasn't a "Freudian" slip. The former president was speaking the simple truth when he decried Putin's war against Ukraine as "the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion." The Iraq War, by contrast, was neither unilateral nor unwarranted. Russia's purpose in Ukraine today is to destroy a democracy and subject its people to the rule of a dictator. The purpose of America and its allies in Iraq was precisely the opposite: to overthrow a dictatorship and raise up a democracy in its place. The moral gulf that separates the two is wide and deep, and should be readily visible to anyone not suffering from advanced Bush Derangement Syndrome.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "On college campuses, all is not yet lost," May 29, 1997:

But one book was different. Milton Friedman's Capitalism and Freedom electrified me. I was riveted by it. Like fireworks lighting up the July 4th sky, Friedman's themes were dazzled me — the genius of markets, the power of prices, the link between prosperity and liberty, the miracles made possible when individuals can choose freely. The sensation was almost physically thrilling. I can still see myself sitting at a study carrel in the GW library, devouring the book's chapters, intoxicated by its ideas, awash with the pleasure of learning. I was experiencing something new — the elation of intellectual discovery. Capitalism and Freedom changed the world as I knew it.

To be sure, Milton Friedman, who began teaching at the University of Chicago in 1947 and won the Nobel Prize in 1976, has changed the world as many knew it. Capitalism and Freedom — already 15 years old when I started college — is one of the modern classics of economics. Between his books, his television series, ("Free to Choose"), and the Newsweek column he wrote for 18 years, he may have educated more people and opened more minds than any other economist in the last 50 years.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Earlier today, with the music that we have heard and that of our National Anthem — I can't claim to know the words of all the national anthems in the world, but I don't know of any other that ends with a question and a challenge as ours does: Does that flag still wave o'er the land of the free and the home of the brave? That is what we must all ask." — President Ronald Reagan, Remarks at Memorial Day Ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery (May 31, 1982)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.