THIS IS AMERICA. If you plan on responding to this column, make sure you do it in English.

Wait a second -- am I allowed to say that?

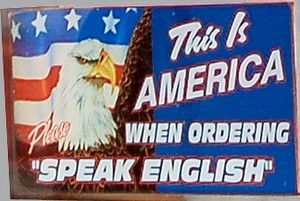

Six months ago, Joey Vento posted a sign saying more or less the same thing -- "This is America. When ordering, please speak English" -- at the takeout window of his popular South Philadelphia cheesesteak joint, Geno's Steaks. As a result he finds himself the target of legal action by the city's Commission on Human Relations, which issued a complaint last week accusing Geno's of discriminating against non-English speakers on the basis of national origin or ancestry. Under the city's Fair Practices Ordinance, the commission will investigate the complaint and could ultimately order Vento to take down his sign or face a fine for refusing.

The sign attracted little notice until the Philadelphia Inquirer ran a story about it on May 30. That set off an avalanche of attention, with appearances by Vento on a slew of national television and radio shows. Papers as far away as Australia have taken note of the case, and more tourists than ever are flocking to Vento's neon-bedecked landmark at 9th Street and Passyunk Avenue.

For all the hullabaloo, though, there are really just two essential facts to this case, and both of them came across clearly in the original Inquirer story. This was the first:

"Vento's political statement -- from a man whose Italian-born grandparents spoke only broken English -- captures the anger and discontent felt by many Americans about illegal immigrants."

And this was the second:

"'If you can't tell me what you want, I can't serve you,' he said. 'It's up to you. If you can't read, if you can't say the word cheese, how can I communicate with you -- and why should I have to bend?'"

In other words, Vento's sign was intended to express a point of view on a controversial public issue -- exactly the type of speech the First Amendment was written to protect. And since he himself apparently speaks only English, telling customers to do the same was a way to keep the long lines at Geno's moving -- not to drive customers away out of bigotry. Geno's would hardly have become a roaring success if its owner had a habit of refusing to serve anyone. Vento says no one has ever been denied service for failing to order in English, and nobody has come forward to contradict him.

But none of that seems to matter to the censors and busybodies who regard Vento and his "speak English" sign as obnoxious and who are ready to shred his freedom of speech to teach him -- and anyone else with politically incorrect opinions about designated victim groups -- a lesson.

"We think it is discriminatory, and we are concerned about the image of Philadelphia," declares the chairman of the Human Relations Commission, the Rev. James Allen Sr. "The issue is not whether anyone has been denied service, but that such a sign discourages people from coming -- asking for service."

But how can a sign written in English discourage people who don't know English? Anyone who has mastered enough English to read Vento's sign presumably knows enough to order a sandwich from his extremely limited menu. Anyone who can't read the sign can't be discouraged or feel discriminated against by what it says.

Besides, since when does the "image of Philadelphia" trump the First Amendment?

In an excruciatingly careful editorial on the flap last Thursday, the Inquirer allowed as how "sure, Vento has free-speech rights. But sometimes one person's right bumps against another person's, and something has to give. Vento is running a public accommodation, just like those lunch counters in the segregated South where African-Americans couldn't get a seat. Some of the arguments that some of Vento's defenders are offering sound awfully familiar from those days.

"To be fair," the editorial quickly added, "the analogy ends there. It's hard to link any actual harm to Vento's English-only grandstanding. He's not accused of actually refusing service to any customer." Then why sideswipe him with the Jim Crow smear? And what exactly is the difference between "grandstanding" and exercising one's right to free speech? If it's "grandstanding" when a sandwich maker posts a seven-word sign in his window, what is it called when a newspaper company publishes hundreds of thousands of copies of a 450-word editorial for distribution?

It is one thing to say that places of public accommodation may not refuse service on the basis of national origin. It is something much more radical to say that a sign exhorting customers to speak English should be illegal, too. Anyone offended by Vento's views is free to boycott his shop and urge others to do the same. But nothing in the Constitution gives those who are offended the right to silence someone else's speech. Agree or disagree with Vento's views, a government that can punish him for expressing them in public is a government that threatens us all.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter or on Parler.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.