IF POLITICIANS discovered cannibals among their constituents, H. L. Mencken once remarked, they would promise the voters missionaries for dinner. The more I see of politicians, and I've seen a lot of them, the more inclined I am to agree with Mencken. In my experience, most candidates for office are shallow and egotistical hucksters who should never be entrusted with the powers of government.

But there are exceptions. Every now and then someone gets into politics for all the right reasons — a candidate who dispels cynicism with optimism and honesty; who runs for office not to exert control but to express gratitude; whose decency is so unmistakable that even opponents can't help acknowledging it.

Not many people in political life fit that description, but I had the great fortune when I was young to work for someone who did. Raymond Shamie, a Massachusetts industrialist who rose from rags to riches, was a Republican who ran twice for the US Senate in the 1980s — challenging Edward Kennedy in 1982, and running in 1984 for an open seat that was won in the end by John Kerry. I was closely involved in both campaigns, and remained in touch with Shamie afterward, when he became chairman of the state's nearly comatose Republican Party and brought it impressively back to life.

Shamie passed away 20 years ago this week, dying of cancer at 78. He was a remarkably good man, kind and honest and down-to-earth, and I can't help thinking how much less degrading and debased politics in this country would be if it attracted more people like Shamie.

Two weeks before his death, I spoke with Shamie for the last time and shared some of our conversation with readers in a column headlined "Ray Shamie's Last Campaign":

Someone did Ray Shamie a kindness when he was 16 years old, and he hasn't forgotten it.

The year was 1937, the depths of the Depression. His father had been killed in a traffic accident and the family was destitute. Shamie, just out of high school, had to go to work so his mother and siblings could eat — but unemployment was at 25 percent, and there was no work to be had.

"You couldn't get any kind of a job in those days," he was reminiscing the other day from his home in Florida. Fortunately, someone in the neighborhood took pity on the Shamies and used his connections to find young Ray a position. And so the truck driver's son from Queens, an exceptionally bright kid with a talent for math and science, entered the workforce as a busboy, washing dishes and mopping floors at a Horn & Hardart automat . But far from resenting his menial job, he still, 62 years later, remembers with gratitude the man who made it possible.

Who would have given odds in 1937 that the penniless kid with the mop would become a millionaire dozens of times over, the founder of high-tech manufacturing firms that would put thousands of men and women to work, a philanthropist who would share his wealth with uncommon generosity?

I first met Ray Shamie in the spring of 1981, soon after he had decided to run against Edward Kennedy in the US Senate race in Massachusetts the following year. I signed on as research director to the fledgling campaign, even as he warned me that he was naive in the ways of politics. (And, he might have added, in the ways of politicians. "I am not going to walk up to some goddam stranger and try to shake his hand," he told me at an early campaign appearance when I urged him to be more assertive about pressing the flesh.)

Eventually he got the hang of shaking hands with total strangers and asking for their support. Most voters, even those who had no intention of voting for a Republican (or against a Kennedy), found it impossible not to be charmed by the avuncular, smiling, earnest candidate. There was no chance, of course, that a political newcomer from the business world would oust Ted Kennedy. But that didn't stop Shamie from pouring himself into the race. "I was so naïve, I actually thought I could win," he would later tell a Boston Globe reporter. "I wasn't politically sophisticated."

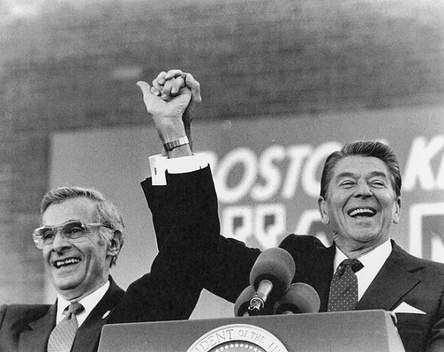

Ray Shamie appeared with President Ronald at a campaign rally in Boston on November 2, 1984. |

Then again, as I wrote after that final conversation, long shots had always been something of a Shamie specialty:

In the mid-1950s, the head of the manufacturing company he worked for told him his notion of a miniaturized, flexible metal diaphragm would never fly commercially. Shamie quit his job, scraped together every dime he could beg and borrow, and launched his own business, Metal Bellows Company. When medical researchers proposed to fit Shamie's bellows into a drug-dispensing pump that could be implanted in a patient's body, his business colleagues panicked, afraid that the risks of liability would be too great. Undeterred, Shamie began making the pump, ultimately launching a second successful business, Infusaid Corporation.

His campaign against Kennedy was less of a success. Still, Shamie earned high points for style and humor, and he succeeded in shaming the senator into meeting him in a televised debate. On Election Day, his message of lower taxes, limited government, greater economic freedom, and support for President Reagan pulled a more-than-respectable 40 percent of the vote.

I was with him two years later when he tried again. Shamie's 1984 Senate campaign was far more serious than the campaign against Kennedy had been. Not because Shamie had changed — he was still an upbeat conservative, still an admirer of Reagan, still an ardent believer in the power of individual initiative and human liberty. But in 1984 he was taken seriously by the media and the political establishment, especially after he demolished a Washington icon, former Attorney General Elliot Richardson, in the Republican primary.

He lost the general election to John Kerry. . . . Yet even in losing, Shamie won. More than 1.1 million voters cast their ballots for him, and he emerged as the most respected figure in the Massachusetts GOP. His long shot had paid off, albeit not in the way he'd intended.

Shamie was not the kind of politician to brag about his IQ, or to hurl insults at political opponents, or to snub reporters. He didn't bellow "Do you know who I am?" when he didn't get immediate attention. And he didn't promise cannibals a supply of government-fattened, taxpayer-subsidized missionaries. Not even his most fervent critics ever imagined that he was dishonest or corruptible or shady. He didn't go into politics because he had developed a craving for personal glory. He ran for office because he wanted to preserve the American culture of liberty and opportunity that had enabled a poor kid mopping floors in an Automat to spin big dreams and make them come true. He entered politics not for himself, but for other kids with mops and big dreams.

An ardent champion of President Reagan's economic policies, Shamie positively glowed when he described how cutting taxes and reducing federal spending would stimulate growth, employment, and prosperity.

"What we have to do is get government spending down, let the economy grow — let it grow through letting people keep more of their own money," he declared with animation during his single debate with Kennedy in 1982. "They do wonderful things with it! They save it, they invest it, they start little businesses — a dress shop, a bakery, a little manufacturing business. They create jobs. They put the profits back into the business. They hire more salesmen, more engineers, they buy more machines, and they hire more people. That's what built America! That's what we have to do."

Those of us who worked on Shamie's campaigns used to refer to him affectionately as "Uncle Sincerity" or "Ray Sincere." Transparent integrity is a priceless commodity, and he was that rare political candidate who had it in spades. He was in politics for the most admirable of reasons: not to advance himself, but to advance his ideas. This country had been good to him, and he wanted it to go on being good to others.

Senator Edward Kennedy agreed to meet Ray Shamie in a single debate during their 1982 campaign. Shamie, whose life was a rags-to-riches success story, used the encounter to provided an animated defense of President Reagan's economic policies. |

Shortly after Shamie's death, I received an e-mail from an admirer of his, who wrote that Shamie was one of the few candidates he had ever voted for wholeheartedly, and not as the lesser of two evils. Then he added this:

One of my friends . . . is an engineer who needed a critical component for a piece of equipment he was building in 1984. He told me that the only one that met the specs, beat every torture test, worked every time without a hitch, was one from Metal Bellows. He absolutely raved about the quality of the materials and workmanship that he saw from them. He also said that everything that he subsequently bought from Metal Bellows was of the same exacting quality.

If more industrialists and politicians were like Ray Shamie, the world would think better of industrialists and politicians. He elevated the world of business and technology; then he enriched civic life in Massachusetts. How lucky we were, those of us privileged to know him.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter