BOSTON WAS ONCE a hub of superb libertarian/conservative talk radio. For years, listeners could tune in daily to erudite, engaging, edifying conversations with on-air hosts who leaned right but who attracted an audience that comprised moderates and liberals as well as conservatives. Avi Nelson, Gene Burns, Jerry Williams — theirs were some of the best-known voices during Boston's golden age of talk radio. But the best known talkmaster of all was David Brudnoy, whose weekday radio program — first on WHDH, then WRKO, then WBZ — consistently drew the largest audience and highest ratings in Boston and New England.

To the multitudes of listeners for whom Brudnoy's conversation was a recurring treat, his death in December 2004 from cancer was a painful blow. It was a measure of how much he meant to so many people that even before he died, his impending death was the biggest news story in town — Page 1 in both daily papers, and the lead on every TV broadcast. He broadcast right up to the end: His final radio show was an interview he did from his deathbed, just hours before he passed away.

"Condemnatory conservatism isn't anything I'm interested in." |

I have been thinking about Brudnoy ever since I realized that his 15th yahrzeit — the anniversary of his death — is just around the corner. Many times over the past decade and a half I have wondered what he would have made of the changes in American politics, culture, and media. It is inconceivable that someone so thoughtful and good-natured would ever have succumbed to the blind tribalism that now pervades public discourse. But would listeners have kept tuning in to his genteel, intellectual, articulate nightly conversations when so many other talkmasters resorted to insulting sneers, naked partisanship, and the lowest common denominator?

Even in his heyday, as I wrote in 2001, Brudnoy's No. 1 rating was something of a paradox.

On the one hand, it is easy to enumerate the virtues of Brudnoy's brand of talk radio. His program is erudite but accessible — "smart talk for everyone," the Boston Globe once called it. He lets his callers have their say and often gives them the last word. He really reads the books of the authors he interviews (and he interviews an awful lot of authors). He is polite, even courtly, to his guests. He absolutely refuses to play to the groundlings: there are no sex jokes, no double entendres, no phony bombast, no psychics, no vulgar sound effects, no webcam.

If you've got half a brain and a dab of intellectual curiosity, how could you not like the Brudnoy show?

Yet Brudnoy's formula is just the one most talk shows avoid.

Ninety-nine talkmasters out of 100 will tell you that cerebral, talky, courteous, ideas-heavy radio programming is sure death in the ratings book. Their market research doubtless proves that listeners have no interest in the kind of show Brudnoy hosts. Except that, manifestly, they do. And have, for 25 years.

Some months ago, I e-mailed David an eye-opening article by Michael Ledeen on Africa's AIDS crisis, with a note suggesting that it might make a great radio topic. I cc'd the note to Ledeen, [who was then] a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, and promptly got a message back: "I LOVE David Brudnoy, the single most literate man on the radio." Countless scholars, authors, and assorted eminentoes would agree.

But authors, scholars, and eminentoes do not generate high ratings. Tens of thousands of loyal listeners, white- and blue-collar both, do — and do they really care about AIDS in Africa?

Jon Keller, political analyst at WLVI-TV (and one-time producer for the David Brudnoy Show), recalls the time he was covering a story at the Grove Hall fire station. "And there were all these tough-as-nails firefighters sitting by a radio, listening to Brudnoy," Keller says. "I asked one of them why he liked it. You know what he answered? 'He tells me stuff I don't already know.'"

Would that guy listen to a conversation about an AIDS epidemic halfway around the world? You bet he would.

By the time I wrote that column, David Brudnoy and I had been friends for almost 20 years. I had often guest-hosted his show, he had been at my wedding, and every few months we managed to get together for lunch to dish about this and that and sort out the state of the universe. Our friendship was a source of great pleasure to me, but it was also a distinction I shared with about a million other people. Brudnoy had an almost preternatural gift for friendship, and his pals were legion — young and old, white and black, gay and straight, Republican and Democrat. There was no philosophical litmus test for his affection. For years he was close to his fellow conservative William F. Buckley, Jr., the legendary editor of National Review — but he was just as fond of Ted Kennedy, their sharp disagreements on most political issues notwithstanding.

Today's "snowflake" mindset — the vehemence with which people loudly proclaim themselves offended and wounded because someone expressed an opinion they reject or criticized a position they support — would have filled Brudnoy with disgust and despair. His entire career was premised on the value of intellectual diversity — on the ability of men and women to grapple with each others' ideas, to take opposite sides in current controversies, without turning disagreement into demonization. The contemporary fervor for "deplatforming" those with the temerity to express opinions that aren't politically correct would have horrified him.

"Condemnatory conservatism," he once said, "isn't anything I'm interested in."

Brudnoy was a gay agnostic and I'm a straight religious Jew; the issues of homosexuality and religious (dis)belief fed some of our longest-running disagreements. In a column published shortly after his death, I recalled that the last time I had been on his radio program we spent an hour debating same-sex marriage — a cause he vigorously supported and I just as vigorously opposed.

But his gayness and agnosticism never put the least dent in our friendship. At my wedding in 1996, still frail after his near-death AIDS experience two years earlier, he didn't join in the dancing — which, in the Orthodox Jewish tradition, wasn't mixed. With mock sternness, I waggled a finger at him and ordered him onto the dance floor. "David, don't you realize we arranged this whole thing just so you could dance with other men in public and not draw any attention?" He roared with delight, and told me he was touched by such solicitude.

The term "Renaissance man" isn't much in use anymore, but if it applied to anyone, it applied to David Brudnoy. In addition to his radio duties, he taught college classes in journalism and communication; he was an indefatigable viewer and reviewer of movies; he contributed hundreds of articles to newspapers and magazines; and he was deeply read in subjects that ranged from political history to Japanese culture.

He was also a tireless traveler. Once we vacationed together in northern Italy, renting a Fiat and driving around Lombardy and the Lake Como region. When I happened to mention that I needed some new suits, he insisted that nothing would do but a trip to Gucci's headquarters in Milan, where he supervised my purchase of what I suppose are the two most stylish outfits I will ever be seen in. On our last day, we made our way to the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery to see Leonardo's da Vinci's The Last Supper , where he gave me a brief tutorial in fresco painting — and then we speculated merrily on which of the disciples recited the Four Questions during the Seder.

I miss David Brudnoy. I miss the decency and fairness that he brought to the public square. I miss the curiosity and integrity and joy of his conversation. I miss his shrewdness and wit. I miss his niceness.

It's been 15 years since I heard his voice. I know I'm not the only one who would give almost anything to hear it again.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Presidential morality, partisan loyalty

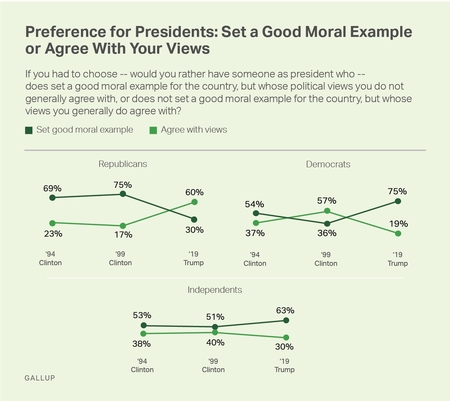

If you had to choose, Gallup recently asked a national sample of American adults, would you want someone as president who sets a good moral example for the country but whose political views you don't generally agree with? Or would you prefer a president who does not set a good moral example for the country, but whose political views you generally find compatible?

The results, when broken down by party affiliation, were stark. An overwhelming 75% of Democrats responded that it was more important for the president to set a good moral example; only 19% placed greater emphasis on agreeing with the president's views. Among Republicans, by contrast, just 30% stressed the significance of an upright moral character versus 60% who said it was more important that a president agree with them on the issues.

So Democrats value moral decency, and Republicans care about politics?

Yes, at the moment. While there's a Republican in the White House.

But what if a Democrat were president?

No need to surmise: Gallup asked the same question in 1999, when Bill Clinton was president and had just been impeached for lying under oath and obstructing justice over his affair with a young intern. Which mattered more back then — the moral example set by a president, or his political positions? By a whopping ration of 75%-to-17%, Republicans insisted that a president's morality was most important. Only 36% of Democrats agreed, while nearly six out of 10 — 57% — were more concerned with compatibility on the issues.

In short, most Republicans care about presidential morality only when a Democrat is president. Most Democrats only think moral leadership matters when a Republican is in the White House. Pretty much the only voters who always say the president should set a good moral example are registered independents. During both the Clinton and Trump impeachment sagas, a majority of independents told Gallup that if they had to choose, they would opt for ethical integrity over political agreement.

"Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people," John Adams wrote in 1798 to a brigade of Massachusetts militiamen. "It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other." He knew how sleazy politics becomes when it isn't restrained by good character. Partisan polarization divides Americans and embitters their politics, but that isn't the worst of it. It also turns them into amoral hypocrites, who demand virtue and honor from leaders only when those leaders belong to the party they oppose — and who dismiss those values as irrelevant when it's their own party that holds power.

It is true, as Trump's defenders constantly argue, that presidents are not elected to be pastors-in-chief. But normative ethics ought to be at least as important in a political leader as the right policy agenda. To quote William Bennett, a former student of philosophy and secretary of education who authored several bestselling books about moral uprightness: "A president whose character manifests itself in patterns of reckless personal conduct, deceit, abuse of power, and contempt for the rule of law cannot be a good president." That passage — and many more like it — appears in The Death of Outrage, in which Bennett shredded the claim made by Clinton loyalists that the president's personal morality was irrelevant, and only his agenda for the nation mattered.

But now that the president "whose character manifests itself in patterns of reckless personal conduct, deceit, abuse of power, and contempt for the rule of law" is Donald Trump, Bennett's view has flipped. His view today is that the president's boorish behavior is beside the point. "What matters are the actions being taken by President Trump and Vice President Pence," he writes, "and they are saving the country."

Sooner or later, the worm will turn again. A sleazy Democrat will be president; Republicans will rediscover a passion for decency and honor in high office. And those of us not wedded to either political party will go on being appalled, wondering where America is bound if indeed it is true that every nation gets the government it deserves.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter