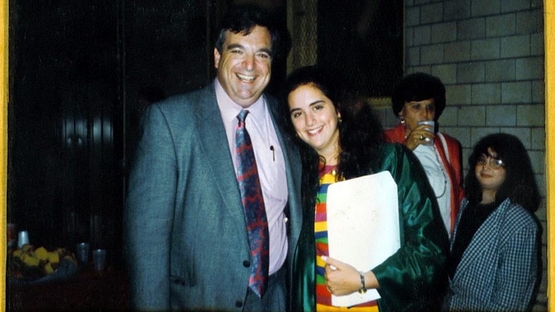

The last photograph taken of Stephen M. Flatow and his daughter, Alisa. In April 1995, Alisa was killed in a terrorist bombing in the Gaza Strip. |

I LEARNED OF Sunday's horrific suicide bombings in Sri Lanka just as I was finishing a new book about an earlier instance of terror.

On the morning of April 9, 1995, a Palestinian suicide terrorist blew up an Israeli bus filled with passengers traveling to Kfar Darom, a town near the Mediterranean shore in the Gaza Strip. Eight people were killed, including Alisa Flatow, a Brandeis University student from New Jersey who was spending a semester abroad. A shard of shrapnel punctured her head, fatally lacerating her brain.

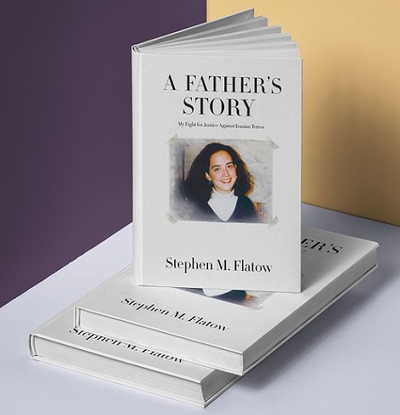

By the time Stephen M. Flatow reached his daughter at the Beersheba hospital to which she had been airlifted, she was already dead. In "A Father's Story," his affecting, intense, and compelling memoir about Alisa's murder and what it led to, he writes that it was too late "to hear my daughter's voice, or see a look of recognition in her eyes, before she died." But it was not too late to turn the awful evil of Alisa's death into a beautiful affirmation of life: Flatow and his wife, Roz, agreed to donate Alisa's vital organs — her heart, pancreas, liver, lungs, and kidneys — to save the lives of six strangers. At the time, such donations were very rare in Israel, and the decision by Alisa's parents caused a sensation. Israel's prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, flew to New Jersey to visit the bereaved family and thank them for the gift of Alisa's organs.

That was only the beginning of Flatow's determination to wring something meaningful and positive from the atrocity that had shattered his world.

"I very much wanted my government to track down and punish the people responsible for Alisa's murder," he writes. "Almost immediately after the attack that killed Alisa, Islamic Jihad sent out a fax taking credit for it. Taking credit for killing my daughter. You can imagine how I felt."

Those of us who haven't lost a loved one to terrorism probably can't fully imagine how he felt, but the families of the 359 men, women, and children blown up in Sri Lanka surely can. On Tuesday, ISIS claimed responsibility for the savage Easter carnage, hailing the suicide bombers as "brothers." Among the slaughtered innocents were several American citizens, including Kieran Shafritz de Zoysa, an 11-year-old from the Sidwell Friends school in Washington, DC, and Dieter Kowalski of Wisconsin, who worked for an educational publishing firm. Nothing will ever make up for what the victims' families have suffered. But they may be able to hold accountable some of those responsible — thanks in part to a 20-year quest for justice that Flatow embarked upon after Alisa's death.

The Kfar Darom bus bombing was carried out by a 22-year-old Islamic Jihad recruit, but he was just a cog in a terror network financed by Iran. Flatow yearned to make the Iranian regime pay for what it had done, but there existed no legal mechanism for doing so. There does now. "A Father's Story" is the tale of how Flatow brought about that change in the law, turning US courtrooms into a venue where American citizens could pursue the world's ultimate terrorist monsters: the governments that sponsor terror groups and the financial institutions through which they operate.

Under longstanding sovereign immunity rules, federal law in 1995 barred Americans from suing foreign governments in US courts. Flatow undertook a marathon of strategizing, lobbying, cajoling, and testifying to get those rules altered. He succeeded when Congress enacted a measure (the "Flatow Amendment"), which stripped immunity from foreign governments designated as state sponsors of terrorism. That enabled Flatow to sue the government of Iran in federal court, the first such suit ever brought on behalf of victims of terrorism. In 1998, a federal judge ruled Iran responsible for Alisa Flatow's death, and awarded her family $247 million.

To collect that judgment, Flatow — soon followed by other families of terror victims — tried to place a lien on Iranian assets held in the United States, including $400 million dollars frozen by the US government after the 1979 seizure of the American embassy in Tehran. He was shocked when the Clinton administration went to court to block him, arguing that the US government needed those frozen assets for leverage in negotiating with Iran. Eventually, after a long struggle, the Flatows agreed to accept a modest fraction of the judgment they had been awarded, on the condition that the funds would eventually be reimbursed out of Iran's frozen assets when a deal was reached to unblock them.

But "A Father's Story" is about much more than legal roadblocks and political skirmishing. Entwined with Flatow's ongoing efforts to open doors so victims of terrorism can seek some measure of recompense from terror-sponsoring regimes is his loving portrait of Alisa — bright, strong-willed, full of laughter, and still grievously missed — and his deeply humane insights into the impact terrorism has on families left to pick up the pieces.

The scourge of modern terrorism is unspeakably evil. The fate that befell Alisa Flatow has befallen so many others; the hundreds murdered in Sri Lanka on Easter are the latest victims, but they won't be the last. In the so-called war on terrorism, there will be no easy, decisive victory. When the terror-masters are finally defeated, it will be because of people like Stephen Flatow — an easygoing New Jersey dad who loved his daughter too much not to fight back against those who stole her life. He has been fighting for more than 20 years, and isn't ready to give up yet.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.