Mark Canha of the Oakland Athletics placed his hand on the shoulder of Bruce Maxwell, who knelt as the national anthem was played before a game Sunday. |

THEY DON'T sing "The Star-Spangled Banner" when the president delivers his State of the Union message, or when Congress convenes, or when Supreme Court justices assemble for oral arguments. The national anthem isn't played at the lighting of the National Christmas Tree or the awarding of the Pulitzer Prizes. It isn't sung at the opening of Broadway plays, or when the first voters show up on Election Day. Worship services in church don't include the national anthem. Neither do movies or Black Friday sales.

So what is it doing at sporting events?

President Trump ignited a firestorm over the weekend when he lashed out at football players who have been kneeling during the national anthem to protest police violence. At a rally in Alabama, Trump goaded NFL team owners to fire any "son of a bitch" who "disrespects our flag," and urged fans to retaliate against the anthem protests: "Leave the stadium. . . . Just pick up and leave." In the ensuing backlash, many more players took a knee or linked arms in solidarity, team owners expressed support for the players, the topic dominated news coverage, and the nation's rancorous public discourse grew even shriller.

But none of this would be happening if no one performed "The Star-Spangled Banner" before football games.

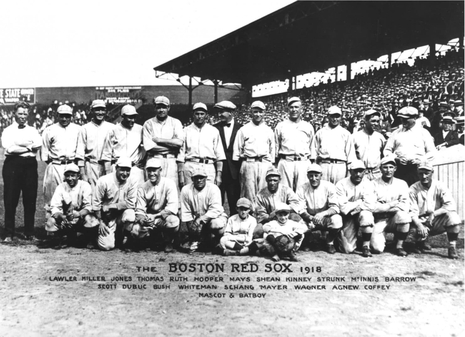

The roots of the ritual go back to World War I, when Major League Baseball encouraged patriotic displays at its games — military drills, for example, and the singing of patriotic songs. During Game 1 of the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs, as the Chicago crowd was taking its seventh-inning stretch, the band started playing "The Star-Spangled Banner." The reaction in the stands, the New York Times reported in its account of the game, was electric:

"The yawn was checked and heads were bared as the ball players turned quickly about and faced the music. . . . First the song was taken up by a few, then others joined, and when the final notes came, a great volume of melody rolled across the field. . . . [T]he onlookers exploded into thunderous applause and rent the air with a cheer that marked the highest point of the day's enthusiasm."

When the Series moved to Boston, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee hired a band to play the "The Star-Spangled Banner" before Games 4, 5, and 6. It soon became a regular feature of special games, such as those played on Opening Day or the Fourth of July. With the outbreak of World War II, the national anthem started being played before every game, football as well as baseball. Japan's surrender in August 1945 ended the war, but NFL Commissioner Elmer Layden decreed that the music would continue: "The National Anthem," he announced, "should be as much a part of every game as the kick-off."

"The Star-Spangled Banner" was first played during the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox (above) and the Chicago Cubs. When a band played the anthem during the 7th-inning stretch, the onlookers "exploded into thunderous applause and rent the air with a cheer." |

Thus was a gesture of spontaneous, heartfelt patriotism transformed into today's enforced display of national loyalty, ripe for exploiting by players or politicians with a disruptive political agenda. Playing the national anthem before every team sport, track meet, and auto race hasn't deepened American unity and love of country. It has tarnished it.

Occasionally, it is true, the performance of "The Star-Spangled Banner" at an athletic event becomes a genuinely uplifting experience. One unforgettable instance was the emotional rendition before the Bruins game at TD Garden after the Marathon bombing in 2013. Another was Whitney Houston's mesmerizing version at the 1991 Super Bowl soon after the start of the Gulf War.

But as a rule, the national anthem before games has no impact at all. Countless fans ignore it, or use it as a bathroom break. When the anthem does leave an impression, it is usually because of something negative: a botched performance, an administrative blunder, a divisive protest.

"The Star-Spangled Banner" deserves better. A compelled show of patriotism no more belongs at a ballpark than it does at a restaurant. Reverence for the flag and love of country are admirable. Treating the national anthem as merely a prelude to sports is anything but.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter