"CONCEALING ONE'S true medical condition from the voting public," the historian Robert Dallek wrote in a 2002 essay, "is a time-honored tradition of the American presidency." During the presidential campaign of 1960, John F. Kennedy went to extreme lengths to hide from voters any hint of his severe medical problems, which ranged from Addison's disease to crippling spinal degeneration. By comparison, Hillary Clinton's recent dissembling over pneumonia and fainting spells is small potatoes.

Hillary Clinton staggered and apparently fainted after leaving a 9/11 memorial ceremony early on Sunday. Her campaign later acknowledged that she often suffers from dehydration, and had been diagnosed with pneumonia two days earlier. |

Kennedy's deception succeeded not only because disclosure standards were so different in his time — public figures were accorded far more privacy than they are now — but also because he was a young man, just 42 when he ran for president. Candidates today can't expect to keep their medical problems secret, especially not candidates as old as Clinton (almost 69) and Donald Trump (70). Last month, the Clinton campaign snorted that Republicans questioning her health were peddling "deranged conspiracy theories." That won't fly anymore.

Already Democratic Party insiders are talking about having a Plan B ready in case Clinton's health problems become insurmountable. On Monday, former Democratic Party chairman Don Fowler urged the party to quickly set up a contingency plan to replace Clinton in case a medical crisis forces her from the race. "It's something you would be a fool not to prepare for," he told Politico.

No major-party presidential candidate has ever been forced by illness, or anything else, to quit the race after winning the nomination. But in 1972, the Democrats' vice-presidential nominee, Senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, had to drop out after it became known that he had been treated for depression with electroshock therapy. The DNC quickly regrouped, naming Sargent Shriver to take Eagleton's place. Now as then, it would be the responsibility of the party to fill any pre-election vacancy in its national ticket — regardless of whether the vacancy were caused by sickness, scandal, death, or mental debility. (Or, for that matter, by party leaders belatedly coming to their senses and realizing that a disastrous nominee was steering the Titanic straight for the iceberg.)

But suppose a vacancy materialized after the November election. Then the power to choose a replacement would no longer belong to the parties, but to the Electoral College.

Presidents are not elected directly by the people, but by state-based slates of electors. Under the Constitution, it is up to the states to appoint electors "in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct." Legislatures need not defer to the popular vote. They can, if they choose, name their state's electors directly, with instructions to vote for someone other than the candidate who won the most votes on Election Day.

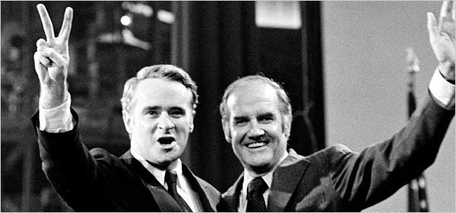

Thomas Eagleton (L) was nominated by the 1972 Democratic convention to be George McGovern's running mate. But he was forced to leave the ticket once it became known that he had been treated for depression with electroshock therapy. |

Clinton's collapse on Sept. 11 was quickly treated, and only a churl would wish her anything but a full recovery. But anything can happen. So far no president-elect has died, become incapacitated, or voluntarily withdrawn in the month and a half between the November election and the convening of the electors. It probably won't happen this year, either.

Yet if the 2016 cycle has taught us anything, it is to rule nothing out. With 70-year-old candidates, it isn't hard to imagine a serious medical crisis, such as a stroke or a massive heart attack, occurring just days after the election. Nor is it that hard — considering how ethically tainted the major-party nominees are — to imagine some devastating post-election revelation (perhaps via WikiLeaks) of wrongdoing or corruption that would make it unthinkable to allow the popular-vote winner to take the oath of office.

The Electoral College is routinely disparaged as undemocratic and archaic, but it exists for the excellent reason that mass democracy can go wrong. The people can be led wildly astray. Or they can make a choice that suddenly turns unviable. Or disaster can strike. Clinton's late-in-the-campaign illness may prove a mere blip. Still, it's a good opportunity to remind ourselves that the Framers built an escape hatch into the presidential election process. Even if voters screw the pooch on Nov. 8, the Electoral College can undo the damage.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.