ELIE WIESEL was Jewish to his core, and in the Jewish state he was revered as a hero — so much so that two Israeli prime ministers offered to nominate him to be the country's president. Yet Wiesel didn't make Israel his home. Though he was a frequent visitor and a passionate advocate, though he felt "attached to the destiny of Israel with all the fiber of his being," as he once put it, he never became an Israeli citizen.

Why not? He himself didn't know, or so he said. But perhaps the explanation was as simple as this: He was in love with the United States.

"The day I received American citizenship was a turning point in my life," Wiesel wrote in a 2004 essay in Parade magazine. "From that day on, I felt privileged to belong to a country which, for two centuries, has stood as a living symbol of all that is charitable and decent to victims of injustice everywhere — a country in which every person is entitled to dream of happiness, peace, and liberty; where those who have are taught to give back."

Like so many others who survived the 20th century's terrible wars and tyrannies, Wiesel had good reason to associate American might with salvation. He was a teenager, emaciated from hunger and shattered by loss, when a detachment of troops from the US 9th Armored Infantry Battalion liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany. "I remember them well," Wiesel later wrote. "Bewildered, disbelieving, they walked around the place, hell on earth. . . . The American soldiers wept and wept with rage and sadness. And we received their tears as if they were heartrending offerings from a wounded and generous humanity."

Wiesel's death has brought forth an international flood of tributes. Understandably, they have focused on the Nobel laureate's singular status as a witness of the Holocaust and on his lifelong mission to arouse awareness and moral outrage in response to the world's evils. Nearly every obituary has recalled the extraordinary moment in 1985 when Wiesel publicly challenged President Ronald Reagan — during a White House ceremony in his own honor, no less — over a forthcoming trip to the Bitburg military cemetery in West Germany, where members of the Nazi SS were buried.

"That place, Mr. President, is not your place," Wiesel bluntly admonished the leader of the free world. "Your place is with the victims of the SS."

Not many have remembered, however, that Wiesel used the same memorable occasion to reiterate his undying affection for his adopted country. What he has felt for America since his liberation in 1945 "nourishes me to the end of my days," he told Reagan. "Mr. President, we are grateful to this country — the greatest democracy in the world, the freest nation in the world, the moral nation."

Wiesel wrote dozens of books, delivered thousands of lectures, touched millions of people. He considered himself first and foremost a teacher, and if a single theme runs through all his teachings, it is the obligation of men and women not to look away, not to be indifferent, when cruelty and horror are being inflicted on the innocent and helpless. Part of what he loved about the United States was its innate concern for the downtrodden — not merely cherishing its own freedom, but taking up arms to restore the freedom of others.

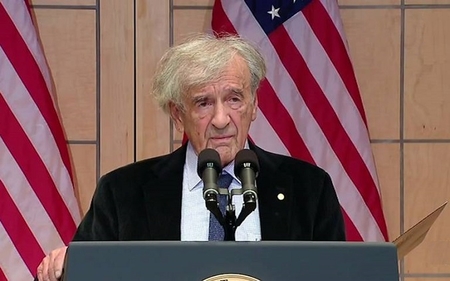

Elie Wiesel receives the US Congressional Gold Medal from President Ronald Reagan at the White House, April 19, 1985. Of his gratitude to his adopted country, Wiesel said "it nourishes me to the end of my days." |

There is a bittersweet poignancy to the timing of Wiesel's death just as Americans were embarking on the Independence Day holiday. "I cannot repress my emotion before the flag and the uniform — anything that represents American heroism in battle," he wrote. His feelings were especially fervent on the Fourth of July. "I reread the Declaration of Independence," said the Nobel laureate, and take heart from its eloquent and moral message: "Opposition to oppression in all its forms, defense of all human liberties, celebration of what is right in social intercourse."

Wiesel, indelibly shaped by the lethal silence of the Holocaust, spent seven decades raising his voice on behalf of the voiceless. Few people, having survived such darkness, have used the experience to shed so much light. And it was American men in arms, entering Buchenwald on April 11, 1945, who made it possible.

Elie Wiesel, the great apostle of memory, never forgot his American liberators, and never stopped loving the country that gave him a second lease on life.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --