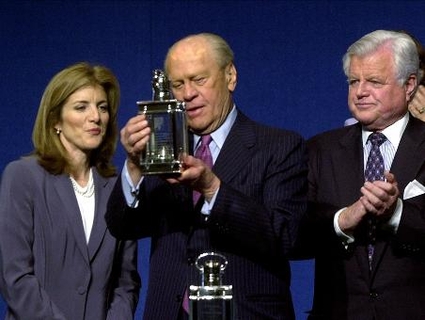

CAROLINE KENNEDY presented former President Gerald Ford with the 2001 Profile in Courage Award this week, saluting his "controversial decision of conscience to pardon former President Nixon and end the national trauma of Watergate." in so doing, she said, he "placed his love of country ahead of his own political future."

But in the days leading up to his bombshell announcement on Sept. 8, 1974, Ford never imagined that his act of clemency would jeopardize his political career. "Sure, there will be criticism," his biographer James Cannon quotes him as saying during an Oval Office meeting eight days earlier. "But it will flare up and die down. If I wait six months, or a year, there will still be a firestorm from the Nixon-haters, as you call them. They wouldn't like it if I waited until he was on his deathbed. But most Americans will understand."

Most Americans didn't understand. A Gallup poll taken shortly after Ford granted Nixon "a full, free, and absolute pardon" found that 59 percent of the public disapproved. Nearly two years later, their ire had barely cooled: In July 1976, 55 percent disapproved.

The reviews were merciless. "This blundering intervention," The New York Times raged, "is a body blow to the president's own credibility." It amounts, fumed The Washington Post, to "nothing less than the continuation of a coverup."

Slamming the pardon as "a betrayal of the public trust" Ted Kennedy demanded, "Is there one system of justice for the average citizen and another system for the high and mighty?" (Brazen words, his critics said, from a man who had himself evaded justice for his fatal misadventure at Chappaquiddick five years earlier.) Ford's own press secretary called it a "double standard of justice" and resigned in protest. In a savage comparison, the American Civil Liberties Union likened it to Nuremberg trials "in which the Nazi leaders would have been let off."

There was a minority view. Elliot Richardson, who had resigned his post as attorney general in what became the Saturday Night Massacre, called the pardon "compassionate and right for the country." Hubert Humphrey said it was "the only decision President Ford could make." And while a Boston Globe editorial suggested that the pardon was "a gross misuse, if not abuse, of presidential power," the paper's Washington bureau chief took a different tack.

"Maybe it's battle fatigue [or] an eagerness to say goodbye forever," wrote Martin Nolan, whose journalism had earned him a place on Nixon's notorious enemies list, but "President Ford's pardon of Richard Nixon is all right with me."

It has taken a while, but Ford's pardon of Nixon is all right with most people now. History often changes hearts and minds that way, elevating villains about whom nothing good can be said into human beings whose motives can be seen as reasonable – even, at times, courageous.

A key lesson of then-Senator John F. Kennedy's book was that political fortitude can be found on both sides of the partisan divide. |

That, of course, was a key message of Profiles in Courage. JFK wrote the book not only to celebrate political fortitude, but to show that it occurs on both sides of the aisle. The senators he profiled were a diverse lot: liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats, Federalists and Whigs. "Some demonstrated courage through their unyielding devotion to absolute principle," he wrote. "Others demonstrated courage through their acceptance of compromise."

But until this year, that lesson appeared to be lost on the Kennedy Library and the Kennedy family. With one exception, the Profile in Courage award had never gone to a Republican – and the exception was John McCain, who was honored for a campaign finance bill most Republicans find odious. For a while, the award seemed to be turning into a consolation prize for haughty liberals whose disdain had turned the voters against them.

In 1992, the honoree was Lowell Weicker, detested in Connecticut for having shoved an income tax through the state Legislature after assuring voters he would never do such a thing. In 1993, the award went to Jim Florio of New Jersey, who had likewise run for governor promising no new taxes, then flagrantly broken his vow. In 1995, the recipient was Mike Synar, an Oklahoma congressman who seemed to specialize in taking positions that his constituents detested – "abrasive and arrogant," Oklahoma's leading paper called him, "quick to label someone who disagrees with him a tool for a special interest."

With its award to President Ford, the award committee has at last followed JFK's lead in looking for courage on the other side of the ideological divide. Ford is the first recipient to be honored for doing something that Ted Kennedy and those close to him once vehemently opposed. President Kennedy would have been pleased.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.