I'VE ALWAYS liked Rudyard Kipling's 1895 poem "If—" , with its four stanzas of rugged, Victorian-era paternal advice. But it wasn't until this month, when my older son Caleb went missing for 80 hours and my wife and I were frantic with worry and fear, that I gained a real appreciation for the virtue with which Kipling's poem opens: "If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs..."

Never before has the quality of levelheadedness meant quite so much to me. As my mind lurched among nightmare scenarios and my gut churned with anxiety, it took an effort of will just to process what was happening. I had no idea how to formulate a plan of action going forward. What are you supposed to do when your teenager has been gone for hours — six hours, 12 hours, 24 hours — and hasn't been seen or heard from? When you've called in the police and given them all the information you can think of? When you've checked your child's usual haunts and come up dry? When his friends, realizing that something is wrong, are beginning to sound the alarm on Facebook and Google Chat? And when the temperature outside is in the single digits — and falling?

Left to our own devices, with no relevant training to draw upon, my wife and I would have been overwhelmed by panic and uncertainty. A natural-born crisis manager I am not. Fortunately there were others — steady, sensible, experienced — who were able to think clearly, set emotion aside, and impose some order on the turmoil. There were three or four such people in particular who stepped forward to help without waiting to be asked. They organized themselves into a kind of war room operation and focused relentlessly, but calmly, on the immediate tasks at hand. How I admire their talent for keeping their heads when it was all I could do not to lose mine.

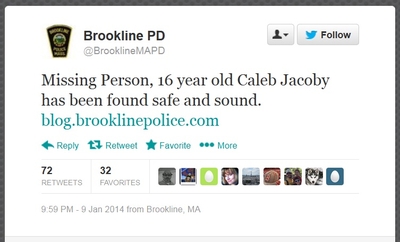

After more than 25 years of working for newspapers, I figured I knew something about stories that grab public attention. But the intensity of interest in my son's disappearance was extraordinary. Of course some of that was due to the public following that comes with a regular byline in the Boston Globe. But I wasn't prepared for the way the news erupted, especially on social media, or how it radiated outward in wider and wider spheres of compassion and concern.

It astonished the police, too. "You have an amazing community here," the detectives working on the case told us more than once. Tips, queries, and offers of help surged into the Brookline police station. Maimonides, the Modern Orthodox Jewish day school where Caleb is an 11th-grader, coordinated a local search effort involving more than 200 volunteers. But offers of aid came pouring in from strangers in other states and countries, many of whom were prepared to drop everything and go anywhere they were needed to search for a teen they didn't know from a city many had never been to.

After 80 hours of anguish and fear, the relief we felt when our son was found was indescribable. |

The "amazing community" that so impressed the detectives wasn't just the community of Maimonides school students, administrators, and graduates, who poured heart and soul into finding Caleb. It wasn't just the broader Jewish community, so often riven by factions and disputes, that momentarily set those differences aside out of concern for a missing boy.

It was more — much more, as I came to understand while trying to make sense of tide of kindness, empathy, and worry that helped keep my family afloat during those agonizing days.

Like the interlocking circles of a Venn diagram, our "amazing community" is really many communities with one family common to all of them. We were embraced and helped and prayed for by people who are connected to us through our son's school or our local synagogue — as well as by others with different connections: residents of Brookline, my colleagues at the Boston Globe, companies my wife has worked for, readers (by no means all fans) of my column, fellow media people, our younger child's school, charities we support, causes we've been involved in, people who know Caleb's far-flung aunts, uncles, and grandparents.

And above and beyond them all, the "amazing community" of parents who have been through their own stresses and storms, and who know from experience that no family is immune to them.

During the worst ordeal of our lives, my family experienced the best that human beings are capable of. That was a blessing I'll never forget, or ever cease being grateful for.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.