FOR WHICH presidential candidate will James Baker, Brent Scowcroft, and Lawrence Eagleburger – the foreign-policy barons of the first Bush administration – vote in November? For the one who shares their Kissingerian approach to foreign affairs, in which order and stability are more important goals than democracy and human rights? Or for George W. Bush?

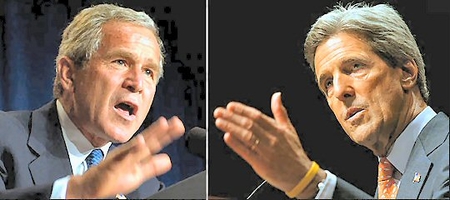

It is an irony of the 2004 presidential campaign that the candidate who most nearly resembles Harry Truman and JFK in believing that America should "pay any price, bear any burden" to promote liberty and democracy in the world is the Republican incumbent, President Bush. Democratic standard-bearer John Kerry, by contrast, articulates a foreign policy that uncannily resembles that of George Bush the Elder. Like Bush I, Kerry has little patience for the idealistic "vision thing." He downplays the idea that the United States should be in the business of advancing freedom around the globe. Considerably more important, he suggests, is keeping the lid on trouble spots.

In a recent interview, the Washington Post reported this week, Kerry made it clear that "as president he would play down the promotion of democracy as a leading goal in dealing with Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, China, and Russia. . . . He demurred when questioned about a number of important countries that suppress human rights and freedoms. He said securing all nuclear materials in Russia, integrating China in the world economy, achieving greater controls over Pakistan's nuclear weapons, or winning greater cooperation on terrorist financing in Saudi Arabia trumped human rights concerns in those nations."

Asked about Pakistan's autocratic military ruler, General Pervez Musharaff, Kerry replied:

"Is he a strongman to a degree? Did he promise elections that have not occurred and all the rest? Yeah. I don't see that as the first thing that is going to happen in our priority of making America safer. It is a long-term goal. . . . But it is not the first thing that has to happen."

Similarly, Kerry told reporters in April that the United States should not get hung up on trying to democratize Iraq.

"I have always said from Day 1 that the goal here . . . is a stable Iraq, not whether or not there's a full democracy," Kerry said. He offered a perfunctory nod to liberal governance – "You hope that you can continue the process of democratization" – but emphasized that "with respect to getting our troops out, the measure is the stability of Iraq." And in case the intended contrast with Bush, who speaks often about the importance of bringing democracy to the Middle East, wasn't clear, Kerry's foreign policy adviser, Rand Beers, underscored it. "We have been concerned for some time," he told the Los Angeles Times, "that Bush's position about having some kind of democratic state was too heroic."

This is how members of the so-called "realist" school of statecraft talk. Theirs is a cautious, managerial worldview, one that values what it sees as concrete interests much more highly than broad democratic ideals or moral causes. Such an attitude has its virtues; it can temper idealism with prudence, and keep policymakers from embarking on hopeless crusades.

But "realism" all too often results in a callous stance unworthy of the United States. It is what kept the first President Bush from publicly protesting when China's communist government massacred pro-democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square 15 years ago this week. It is what led him to send 400,000 troops to rescue Kuwait (and protect Saudi Arabia) from Saddam Hussein – and then order those troops to sit on their hands while Saddam brutally crushed a popular uprising against his murderous regime.

The problem with Kerry-Bush I realpolitik is that the stability it champions is often beneficial only in the short term, and sometimes not even then. American backing for Middle Eastern dictatorships helped turn the region into an incubator of terrorism. The supposedly "realistic" decision to bolster Saudi Arabia's royal family by leaving thousands of US troops within its borders after the Gulf War inflamed an Islamist fanatic named Osama bin Laden. Iraq under Saddam was certainly stable. It was also a threat to its neighbors, a supporter of terrorism, and a savage violator of human rights.

Truman, JFK, and Ronald Reagan understood that an explicit policy of advancing democracy in the world advances America's interests as well. Bush II came to understand this only after 9/11, when he saw the horror that abandoning the Middle East to its unfree and undemocratic "stability" could lead to. Since then it has become the central pillar of his foreign policy, and a key strategy in the war on terrorism.

"Sixty years of Western nations excusing and accommodating the lack of freedom in the Middle East did nothing to make us safe," Bush said in an important address to the National Endowment for Democracy last November, "because in the long run, stability cannot be purchased at the expense of liberty. As long as the Middle East remains a place where freedom does not flourish, it will remain a place of stagnation, resentment, and violence ready for export."

A free and democratic Middle East will do more to make America secure in the long run than Kerry's focus on stability will. Whether Bush can make good on his vow to transform the region is very much an open question. It is an enormous undertaking, and Bush may fail. But his eye is on the right prize. His opponent's – like his father's – isn't.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.