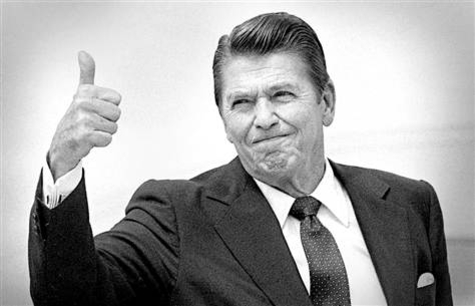

RONALD REAGAN was the first president I was old enough to vote for, and the only one I have ever voted for with enthusiasm. He was the pre-eminent influence on my political coming of age – so much so that to this day, "Reaganite" is the label that best sums up my political world view.

For those of us who so admired Reagan during his presidency – and who remember the mockery and disdain to which he was so often subjected – the tributes that have been pouring forth since Saturday help make the sorrow of his death, and of the awful sickness that preceded it, more bearable. History, as he always knew it would, has vindicated him. The man once dismissed as an "amiable dunce" and reviled as a warmonger is now acknowledged as a courageous visionary, an apostle of decency and liberty who left the world far better than he found it.

"The American sound," Reagan said in his second inaugural address, "is hopeful, big-hearted, idealistic, daring, decent, and fair." Much the same could be said of Reagan himself. All week long, the accolades have emphasized the character and values that made him the man he was – his optimism, his patriotism, his self-deprecating humor, his moral clarity, his rocklike belief that freedom is the birthright of every human being, his willingness to call evil by its name, his faith in God, his sheer guts.

But one trait has gone largely unmentioned: His remarkable humility.

In her moving and affectionate account of the 40th president's life, When Character Was King, Peggy Noonan says that when she really wants to convey what Reagan was like, she tells the "bathroom story."

It occurred in 1981, shortly after the assassination attempt. Reagan was still in the hospital and one night, feeling unwell, he got out of bed to go to the bathroom. "He slapped water on his face, and water slopped out of the sink," Noonan relates. "He got some paper towels and got down on the floor to clean it up. An aide came in and said, 'Mr. President, what are you doing? We have people for that.' And Reagan said oh, no, he was just cleaning up his mess, he didn't want a nurse to have to do it."

That was Reagan: On his say-so armies would march and fighter jets scramble, but he hated to trouble a hospital orderly to mop up his spill. That humbleness, it seems to me, is a mark of Reagan's greatness, too — and a key to understanding the outpouring of affection his death has unleashed.

Though he came from nothing – poor family, alcoholic father, no status, nothing to boast about – Reagan considered himself no less entitled to respect and a chance to prove himself than those who had much more. But if no man was his better, neither was he the better of any man. That instinctive sense of the equality of all Americans never left him – not even when he was the one with fame and power.

I don't think I have ever heard a story about Reagan in which he came across as arrogant or supercilious. In a number of reminiscences this week, former staffers have described what it was like to work for the president. Several have recalled how, even when they were at the bottom of the pecking order, he never made them feel small or unworthy of notice. To the contrary: He noticed them, talked to them, made them feel special.

Reagan climbed as high as anyone in our age can climb. But it wasn't ego or a craving for honor and status that drove him, and he never lost his empathy for ordinary Americans — or his connection with them, as we now know from his private correspondence.

He was a lifelong letter-writer – perhaps the most prolific correspondent of any president since Jefferson. A collection of his letters was published last year (Reagan: A Life in Letters), and it is striking to see how many of them were written – by hand, usually – to angry or disappointed critics, many of them unimportant people he had never met. He is unfailingly polite and respectful; often he is touchingly earnest in his attempt to get them to see his side of an issue.

And why would the president of the United States devote so much time to answering mail from complete nobodies? In part because he never forgot his own modest roots. He was a genuinely humble man, one who didn't scorn others as "complete nobodies." For who knew better than he just how far a "nobody" from nowhere might someday go?

On June 3, 1984, Reagan visited Ballyporeen, the County Tipperary hamlet where his great-grandfather was born in 1828.

"Today I come back to you as a descendant of people who are buried here in paupers' graves," he said. "Perhaps this is God's way of reminding us that we must always treat every individual, no matter what his or her station in life, with dignity and respect. And who knows? Someday that person's child or grandchild might grow up to become the prime minister of Ireland – or president of the United States."

In his first inaugural address, Reagan described George Washington as both "a monumental man" and "a man of humility." The two qualities merged in the nation's first president. They merged again in the 40th. May he rest in peace.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe. His website is www.JeffJacoby.com).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby on Facebook.