I DIDN'T LEARN of the space shuttle disaster until Saturday night, a good 10 hours after it happened. Earlier in the day, when so much of the nation was reeling in shock, I was reading to my son from one of his current favorites, a book of stories about scientists and inventors. Our story that day was "Danger Beneath the Ice," which described an episode in the life of Jean Louis Agassiz, the renowned 19th-century naturalist and educator.

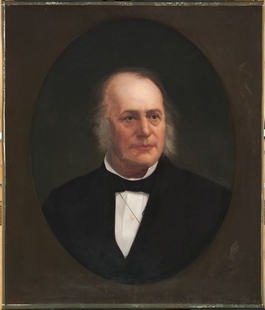

Jean Louis Agassiz |

One of Agassiz's passions was the study of glaciers. It was he who discovered that glaciers moved and deduced that Europe and North America had long ago been transformed by the flow of immense rivers of ice. Much of his knowledge was acquired firsthand, often under highly dangerous conditions.

The incident we were reading about occurred high in the Swiss Alps in the 1830s, when Agassiz, intent on learning what the interior of a glacier was like, had himself lowered into one -- something no one had ever done. Suspended only by a rope swing, unable to communicate with his men except by jerking on the line, he slowly descended into a freezing glacier well. When he was more than 125 feet below the surface, his feet hit a pool of icy water. Frantically, Agassiz signaled to be pulled back up, but his tug on the rope was misunderstood. Not until he was nearly up to his neck in the bitterly cold water -- and just minutes away from drowning or freezing to death -- did his companions realize that he was in trouble and pull him back to safety.

My son, who is not quite 6, was full of questions. Why did "Louis" (as he was called in the story) have to go into the glacier himself? Why did he want to see what was inside? Why didn't he know how dangerous it was? What if the others hadn't pulled him out in time?

I explained that there have always been people who want to learn as much as they can about the world -- and that some men and women are so driven to learn that they will do things and go places and take chances that other people won't. Sometimes, I told him, the only way to really understand something is to see it or try it yourself. We decided that "Louis" probably would have gone beneath the ice even if he had known that it was risking death to do so.

Only later, when my son was getting ready for bed, did I learn what had happened in the skies over Texas that morning.

The critics went to work almost as soon as Columbia fell to earth: criticism of the vehicle, of the shuttle program, of NASA's safety record. And yet it was impossible not to notice that the most emphatic reaction of all was the defiant insistence that we -- we humans, that is, not just we Americans -- would never give it up, this compulsion to seek out the unknown and expand human understanding. From the president on down, officials whose first instinct after a tragedy is usually to ban or restrict something reacted instead with a vow to press on.

"This cause of exploration and discovery is not an option we choose," George W. Bush said. "It is a desire written in the human heart." Sure enough, a Gallup poll taken just one day after the disaster found 82 percent of the public in favor of continuing to send human beings into space. Even the grieving families of the dead astronauts declared through their tears that "the bold exploration of space must go on . . . for the benefit of our children and yours."

Like my son, I was introduced early to the human craving to push back frontiers. As a 5- or 6-year-old, I received the first set of books I ever owned: a series of first-grade readers about the great explorers. I own them still: "De Soto," "Christopher Columbus," "The Norsemen," "Marco Polo," "Admiral Richard E. Byrd," "Colonel John Glenn," and half a dozen others. They are short and very simply worded, yet considerably more mature than the empty mush written for very young readers today.

As I look them over now for the first time in many years, I see that I wasn't sheltered from the hard truth that exploration and discovery are not cost-free. In "Magellan," sailors succumb to hunger and thirst and Magellan himself dies (actually, he was killed) before completing his journey. In "Henry Hudson," mutineers put the great navigator and his son off the ship, leaving them to die in what is now Hudson Bay. John Glenn splashes down, unharmed -- but not before his capsule becomes a "fireball" during re-entry and he fears it may burn up.

Unlike Glenn's Friendship 7, the seven friends aboard the Columbia did not make it safely back to earth. But their deaths will not halt the exploration of space any more than the deaths of Robert Scott and his crew halted the exploration of Antarctica -- or than the death of Agassiz would have halted the investigation of glaciers. I have heard and read more about lunar bases and a manned mission to Mars in the past five days than I can remember hearing or reading in the previous 15 years. We mourn the voyagers who are lost, but the voyaging never ends.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.