ARE YOU GLUM about the nation's prospects? If so, you've got lots of company.

According to a recent poll for The Hill, a Washington-based daily, 69 percent of American voters say the US is declining, and 83 percent of voters describe themselves as worried (49 percent say very worried) about the country's future. Worldwide, the Pew Research Center finds in a separate poll, "many now see the financially-strapped US as a great power in decline." Among respondents in 18 countries, 47 percent expect China to replace the United States as the world's leading power. Only 36 percent disagree.

"America's best days are yet to come," Ronald Reagan often declared. But in a Rasmussen survey late last month, just 37 percent of likely voters shared that sentiment, while 45 percent thought America's best days were past.

So it's no surprise that when Commentary magazine, for a symposium published in its current issue, asks 41 American thinkers whether they're optimistic or pessimistic about America's future, there is pessimism aplenty among the responses.

Columnist David Brooks, for example, laments the "consumption-oriented" narcissism of American society, and the "fiscal crackup" it's bringing on. Kay Hymowitz, a Manhattan Institute scholar, expresses alarm at the breakdown of family life, including the "sharp rise in divorce and out-of-wedlock childbearing among the less-educated middle class." Former Undersecretary of State James K. Glassman is distressed that "America's will to lead seems to be slipping away," and that isolationism is rising on both right and left. Dennis Prager, the radio host and ethicist, sees an assault on the "American Trinity" -- the values proclaimed on every US coin: Liberty, E Pluribus Unum, and In God We Trust.

"Obesity already affects a third of our population, and will likely affect 50 percent of us by 2030," writes novelist Kate Christensen, while Dana Gioia, the former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, bewails "a vast dumbing-down of our public culture that may already be irreversible."

They and other contributors to Commentary's symposium make it clear that the case for pessimism is compelling and daunting. Anyone seeking evidence that the United States is now a "Republic in twilight," as the essayist Mark Steyn puts it, can find it with depressing ease.

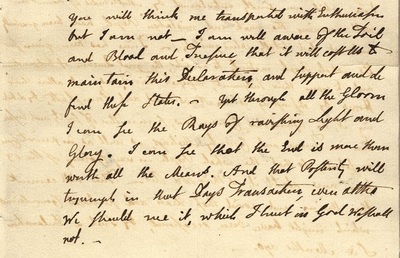

And yet when hasn't America been confronted with dire challenges? From "the starving time" at Plymouth Plantation to the sack of Washington during the War of 1812 to the terror and confusion of 9/11, there have always been reasons to be depressed about the nation's prognosis. And there have always been Americans who refused to be depressed. Writing from Philadelphia in July 1776, John Adams acknowledged the struggle and sacrifice that American independence would require. "Yet through all the gloom," he assured his wife Abigail, "I can see the rays of light and glory."

Several participants in Commentary's symposium likewise see through gloom of the present to American triumphs yet to come. John Podhoretz, the magazine's editor, is buoyed by the fact that even amid the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, "there are surprisingly few signs of social instability" in the United States. Here -- unlike, say, Greece -- political upheaval has generally been channeled through the voting booth, and voters have "demonstrated a remarkable, almost unprecedented taste for shifting direction" when politicians have let them down.

No less valuable than our national political flexibility is something that R.R. Reno, the editor of the journal First Things, points to: the extraordinary absorptive power of "the American myth" -- the civil religion of freedom and justice that animates American patriotism. That common culture is what "reabsorbed a defeated South after the Civil War" and "waves of immigrants" and "even the children of ex-slaves, whose suffering and humiliation should have made them eternal enemies."

"I am well aware of the toil, and blood, and treasure, that it will cost us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these states. Yet, through all the gloom, I can see the rays of light and glory. I can see that the end is more than worth all the means" -- John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776 |

Reno isn't the only Commentary contributor who points to America's ability to assimilate outsiders as a singular advantage in the present, and an ongoing reason for optimism about the future. Yes, remarks Harvard's Joseph Nye, China can draw on a talent pool of 1.3 billion people, "but the United States can draw on a talent pool of 7 billion." From every corner of the globe, dreamers, strivers, and self-starters have been willing to uproot themselves for the chance to make a better life in this astonishing land of opportunity.

"Optimism, by nearly all accounts, has been an integral part of our national DNA," writes James Ceaser, a scholar of American politics at the University of Virginia. The crises of the moment -- a limping economy, soaring government debt, a stifling bureaucracy -- are undoubtedly serious. But they are far from insoluble, and they certainly aren't grounds for terminal pessimism.

The nation that transformed an undeveloped wilderness into history's freest, most prosperous superpower; that overcame the cancer of slavery; that trounced totalitarianism; that still inspires the persecuted and downtrodden -- that nation isn't about to fade to gray. We have licked worse problems than those we face now.

Optimistic or pessimistic about America's future? The Gipper had it right: Our best days are yet to come. This nation has had a remarkable run, but you ain't seen nothin' yet.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter