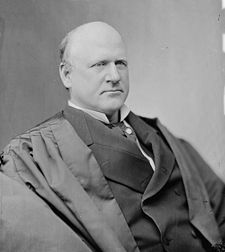

IN 1896, Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan penned the greatest dissent in the history of American jurisprudence. In 1996, every Democrat in the California Assembly voted against a resolution commemorating Harlan's masterpiece. That is the preposterous corner into which opponents of the California Civil Rights Initiative -- the ballot initiative, known as Proposition 209, that would ban state discrimination on the basis of race or gender -- have painted themselves.

The case that occasioned Harlan's dissent was Plessy v. Ferguson. At stake were the racist Jim Crow laws of the Old South. In what would prove the most toxic judicial decision since Dred Scott, eight of the high court's justices concluded that state-sponsored racial segregation was lawful. They ruled that the 14th Amendment -- despite guaranteeing "equal protection of the laws" to every citizen -- did not prohibit "distinction based on color." It was the ruling white supremacists had been hoping for, and it crushed all hope of civil rights for another 60 years.

Only Justice Harlan protested.

"Our Constitution is color-blind," wrote Justice John Marshall Harlan in his famous dissent, "and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." |

"Our Constitution is color-blind," he wrote in angry dissent, "and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. . . . The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights . . . are involved."

Harlan stood alone in 1896, but the seed he planted eventually germinated. Decades later, when the NAACP Legal Defense Fund launched its litigation strategy to end racial segregation, Harlan's dissent was its wellspring and inspiration.

In 1948, for example, the NAACP sued the University of Oklahoma, which claimed the right to exclude blacks from its law school as long as the state created a "separate but equal" nonwhite law school. In pursuing the case up to the Supreme Court, the NAACP's chief litigator -- Thurgood Marshall -- insisted on a principle that could have come right from Harlan's dissent. "Classifications and distinctions based on race or color," Marshall argued, "have no moral or legal validity in our society."

Six years later came Brown v. Board of Education. Unanimously, the Supreme Court held that "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate-but-equal' has no place." Harlan was long gone, but his words had borne fruit at last. "His lonely dissent," the New York Times observed, had finally "become in effect . . . a part of the law of the land."

Yet in the four decades that followed, a new array of racial preferences, quotas, and set-asides was enshrined into law. In the name of tearing down discrimination, a new edifice of discrimination was built up. More than ever before, public benefits today are conferred or withheld on the basis of race and ethnicity.

So when California Assemblyman Bernie Richter offered a resolution earlier this year to mark the centennial of the Harlan dissent, urging Californians "to read and understand Justice Harlan's words" and beware "the damage that racism and discrimination can cause," every Democrat in the chamber voted no. Better to turn their backs on Harlan's great moral teaching, they decided, than to do anything that might help Proposition 209.

Were he alive at this hour, Harlan would endorse the proposed law in a heartbeat. It embodies his profoundest conviction -- that the law may not play favorites. Its language could not be more clear: "The state," Prop 209 commands, "shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education or public contracting."

Lord knows what the pro-quota forces would do to Harlan if he were still around to insist on equality under the law. In their campaign to defeat the measure, they have taken the lowest of low roads. Nonwhite supporters of Prop 209 have been tarred as "Uncle Toms" and "traitors." Anti-209 students at a California State University campus invited neo-Nazi David Duke to "defend" the initiative. The opponents of colorblind law have not even scrupled to insult a young widow who allowed the Yes on 209 campaign to tell her story in a radio ad.

The woman's name is Janice Camarena. Her story is one Justice Harlan would have recognized.

On January 19, 1994, Camarena showed up for the 11 a.m. session of English 101 at San Bernardino Community College. She and another woman were the only white students in the class; as soon as the instructor noticed them, the two women were ordered to leave. That session of English 101, it turned out, was reserved for blacks only.

A century earlier, Homer Plessy had boarded a train in New Orleans. He was the only black passenger in the car; as soon as the conductor noticed him, Plessy was ordered to leave. That railway car, it turned out, was reserved for whites only.

Discrimination by race is discrimination by race. There is no moral difference between whites-only trains and blacks-only classrooms. Call it "separate-but-equal" or call it "affirmative action" -- any law that metes out different treatment to different races is pernicious. What happened to Janice Camarena is as poisonous as what happened to Homer Plessy. Justice Harlan would have understood. Will California's voters?

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.