SHOULD HEALTH INSURERS be compelled to cover colorectal cancer screenings? The American Cancer Society has good reasons to say yes. There are better ones to say no.

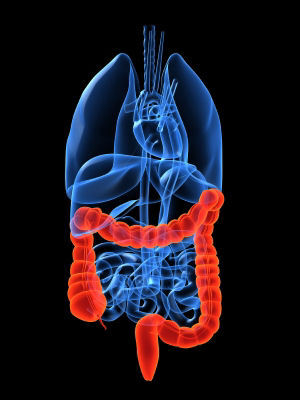

Colorectal cancer kills nearly 50,000 Americans each year, making it the second-leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Yet when diagnosed early, colorectal cancer is highly treatable; it generally turns life-threatening only when it has time to metastasize to other organs. That means that colorectal cancer screening, which can detect the disease in its earliest stages, is one of the best ways known to reduce cancer mortality -- and reduce as well the enormous costs involved in treating patients with late-stage cancer.

So it isn't surprising that in recent years more than half the states (plus the District of Columbia) have passed laws making screening tests for colorectal cancer a mandatory health-insurance benefit. Nor does it come as a surprise that the American Cancer Society would lobby to get such mandates enacted in states like Massachusetts that haven't yet done so.

Accordingly, when Bay State lawmakers took up the issue at a hearing last week, the society's spokesman made a seemingly straightforward argument: More Americans would get these potentially life- and cost-saving tests if their health insurance policies covered them, so the law should require such coverage. He buttressed his case with data suggesting that colorectal screening rates have risen faster in states that adopt screening mandates. And he cited a study concluding that the price tag of such a mandate in Massachusetts would be about $8.50 per health-plan member per year -- far less than the $300,000 and up it can cost to treat a patient with late-stage colorectal cancer.

Case closed, then? Not so fast.

"From a distance, cancer screening seems to be the exact sort of thing that we should mandate," observes David Gratzer, a Canada-trained physician and an expert on health-care policy at the Manhattan Institute. "It's important; it saves lives; it seems right." Question the wisdom of making it a compulsory insurance benefit, he says, and people demand to know: "Why don't you believe in cancer screening?"

But no one disputes the importance of screening for colorectal cancer, least of all insurers. Even without a statutory mandate, commercial health insurance companies in Massachusetts have for years been covering the cost of screening for colon and rectal cancer. That undoubtedly helps explain why screening rates in the state have been among the nation's highest.

In 2008, among Massachusetts women age 50 and older, 69 percent had been screened for colorectal cancer -- more than in 43 other states. When the Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy analyzed the proposed new mandate in a report last December, it found that the screening rate of virtually all health plans that would be covered by the bill already "ranges between 72 and 78 percent." If the American Cancer Society's goal is to make such screening widespread and routine, it can rest easy: Massachusetts has largely met that goal. And it didn't need a law to do so.

The bill would change one thing: In addition to colorectal screening procedures like colonoscopies or fecal occult blood testing, for which there is near-unanimous support in the medical profession, it would require insurers to pay for two on which expert opinion is still unsettled: the fecal DNA test, which is not recommended by American College of Gastroenterologists, and CT colonography (or "virtual colonoscopy"), the effectiveness of which is still being studied. The National Cancer Institute, for example, notes that "whether virtual colonoscopy can reduce the number of deaths from colorectal cancer is not yet known."

Health insurance mandates may spring from good intentions. But good intentions don't equal good policy, and their ultimate effect is to make insurance more costly for everyone. |

Were health insurers flatly refusing to cover any colorectal cancer screening, a legislative mandate might be easier to justify. But insurance companies readily pay for screening tests that are widely supported, while waiting for the medical efficacy of others to be clarified. That strikes a reasonable balance -- more reasonable, surely, than inviting lawmakers to mandate by law screening techniques that researchers and clinicians are still assessing.

Most insurance mandates may spring from good intentions. But good intentions don't equal good policy, and their ultimate effect is often to make a serious problem -- like the cost of health care -- even worse.

As it is, mandated benefits in Massachusetts -- 47 of them, according to the Council for Affordable Health Insurance -- cost the state an estimated $1.3 billion a year. With insurance premiums sky-high, the last thing lawmakers should be considering are mandates that will drive them higher still. Colorectal cancer screening is important. So is insurance that consumers can afford.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.