THERE ARE PLENTY of black faces at the Republican National Convention, but few of them are the faces of delegates. There are black police officers here, black technicians, black security guards, black journalists. But black Republicans? Not too many.

According to a Los Angeles Times census of the convention's 1,990 delegates, 88 percent are white, 3 percent are black, and the remainder are Asians, Hispanics, and American Indians. Some state delegations are less monochromatic than others -- California's is 27 percent nonwhite -- but by and large, the traditional loyalty of American blacks to the Democratic Party is reflected on the floor of the GOP convention.

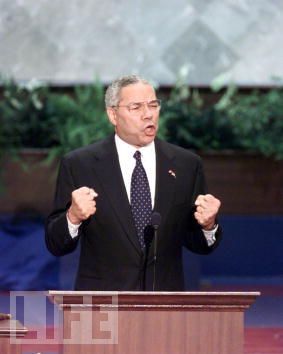

"I became a Republican," Colin Powell told the GOP convention, "because I believe in . . . the American Dream." |

There is a sense, expressed by many here, of a corner being turned -- a feeling that the long estrangement of African-Americans from the party of Lincoln and Emancipation may finally be coming to an end.

Clearly, something is shifting.

When an immensely popular black general headlines the opening of the GOP convention and declares, "I became a Republican because I believe in . . . the American Dream," it is -- as Jack Kemp said on Tuesday -- a defining moment. No less defining is the giddy enthusiasm for Kemp himself, a conservative hero who tears up when he speaks of Nelson Mandela and who seems to quote "Dr. King" 10 times a day.

Meanwhile, at least 24 blacks (and about a dozen Hispanics) are running for Congress on the Republican ticket this year. Americans for a Brighter Future, a black-run political action committee that funnels money to nonwhite Republican candidates, has top GOP officials lining up to join its board of directors. Black Republican officeholders, few though they are, move easily among the mover-and-shaker receptions that have been filling this town. Black Republican office-seekers are introduced from the convention podium. Yet little if any of what they say or do is racial. For all the talk of "inclusion" and "diversity," the reasons nonwhite Republicans here give to explain their party affiliation have nothing to do with color or ethnicity.

"If I'm black, I must be a Democrat, right?" asks Raynard Jackson, the chairman of Americans for a Brighter Future. "But I just discovered I was in natural sync with the Republicans."

Deborah Wright, a Republican candidate for Congress from Oakland, Calif., is equally straightforward. "I'm a Republican because I don't agree with the Democrats. My No. 1 principle is freedom. I'm opposed to high taxes because it eats away our freedom. So why would I be a Democrat?"

A reporter asks Joe Rogers, a black Republican running for the Denver seat being vacated by Rep. Patricia Schroeder, to list his top three priorities. "Business development," he promptly says. "Job creation. Stronger families." Note that those are Republican priorities, not "black" ones.

Powell's speech to the convention -- despite his dissent on abortion and affirmative action -- is the best example of all. The theme Powell hammered home hardest was the quintessential Republican demand for smaller government. He called for rolling back the federal bureaucracy not once, not twice, but seven times. "I became a Republican -- like you," he declared, "because I truly believe the federal government has become too large and too intrusive in our lives."

It has been said 10,000 times this week -- it will be repeated 10,000 more when the Democrats are in Chicago -- that nothing actually happens at these conventions. And, actually, nothing does. But something is happening between blacks and Republicans. Slowly but steadily, African-Americans are embracing Republican ideas; slowly but steadily, Republicans are opening their arms to African-Americans. The one is symbolized by Powell's speech; the other, by the nomination of Kemp.

Bill Brock, the former labor secretary and Tennessee senator, recalled the other day that when he became the GOP's national chairman in 1976, the party was in dire straits. Richard Nixon had resigned in disgrace, scores of Democratic freshmen had swept into Congress, and Gerald Ford had just lost the White House. "We were in the dumps," Brock said. "Things were so bad that some people wondered if the Republican Party shouldn't just change its name and start over."

But Mary Louise Smith, Brock's predecessor as chairman, fought the idea. "We don't have to change the party's name," she insisted. "We have to live up to it."

Twenty years on, the most encouraging evidence that her admonition is being taken to heart is the nomination of America's foremost civil rights Republican for vice president -- and the Republican message of America's foremost black leader.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Join the Fans of Jeff Jacoby on Facebook.