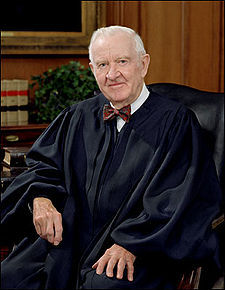

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens |

At an American Bar Association convention in Orlando, Stevens expressed his disdain for "jurisdictions that continue the most unwise practice of electing their judges." That, he sniffed, "is comparable to allowing football fans to elect the referees." He charged lawyers in those benighted states where voters judge the judges to agitate for a "change in the selection process." Why? Because, lectured Stevens, "making the retention of judicial office dependent on the popularity of the judge inevitably affects the decisional process in high-visibility cases, no matter how competent and how conscientious the judge may be."

The belief that lofty government officials should be spared the indignity of elections is not a new one. Stevens' arguments against democracy for judges echo those that used to be made, before there was a Seventeenth Amendment, against democracy for senators. The antidemocrats lost that argument, just as they lost the earlier argument over how much real power the Electoral College would have. Just as they lost the argument over letting voters pass and repeal laws through initiatives and referenda.

Of course there is a case to be made against electing judges. But a similar case can be made against electing anybody.

"Persons who undertake the task of administering justice impartially," Stevens says, "should not be required -- indeed, they should not be permitted -- to . . . curry the favor of voters by making predictions or promises about how they will decide cases." If that is true of mere judges, it must be even truer of presidents. Do we really want the commander-in-chief, the leader of the Free World, the man on whose word armies march and the NASDAQ falls, currying the favor of voters with predictions and promises? And what about governors? Treasurers? Attorneys general? Wouldn't they perform their duties with more integrity and selflessness if they never had to think of re-election?

Perhaps they would. But the core principle of democratic republicanism is that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. We have the right to choose our rulers, and no branch of government -- not the executive, not the legislative, not the judicial -- should be declared off limits to voters. Even if the trade-off is that we end up being governed by something less than pure and disinterested philosopher-kings.

Regrettably, federal judges are named for life. The Constitution's framers believed -- wrongly, as it turned out -- that the judiciary would be weak and easily intimidated, and thought only permanent appointments could ensure judicial independence. The unhappy result is that federal judges serve until they die or retire, no matter how incompetent or intolerable they become. A bad judge can be removed only by impeachment in Congress; voters have no recourse at all. Stevens may find that antidemocratic process agreeable. Most of America would differ.

According to data compiled by the US Department of Justice, only Rhode Island grants life tenure to its judges; in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, they serve until age 70. Everywhere else, judges serve for a term of years, and 40 states permit additional terms only with voter approval. If Stevens is right -- if "making the retention of judicial office dependent on the popularity of the judge inevitably affects the decisional process" -- then 40 state judiciaries are tainted. Does Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, an alumna of the Arizona Court of Appeals, share her colleague's view?

None of this is to say that judges should demean themselves in partisan elections, or engage in hard-sell fundraising and sleazy campaigns. It is to say that democracy and judicial integrity can go hand in hand.

The most enlightened court systems are those that blend executive appointment with a public vote, as is done -- for example -- in Colorado, California, and Oklahoma. The governor selects a judge with the advice of a nominating commission; the judge serves a fixed number of years; the voters then decide, on a nonpartisan ballot, whether to retain her for another term. Judges don't have to run against each other or campaign to get on the bench. But from Day 1 they know that the people in whose name they pass judgment will eventually pass judgment on them.

In practice, judges in these states are almost always retained. Rarely do voters find a judge noxious enough to fire. But the option is available if necessary. And when it does happen, says Oklahoma newspaperman Patrick McGuigan, a historian of judicial politics, "the sun rises the next day."

Justice Stevens was appointed to the federal bench in 1970; his antidemocratic impulses may reflect the fact that for 26 years, he has been beyond voters' reach. His notion that all judges should be so insulated ought to be stopped before it gets started. No less than presidents, senators, or county commissioners, judges are public servants. They should be accountable to their masters.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Join the Fans of Jeff Jacoby on Facebook.