EVERY SENTIENT HUMAN BEING knows that smoking is unhealthy. Cigarettes have been nicknamed "coffin nails" since at least the 1880s, and more than two centuries earlier King James I was railing against smoking as "a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, [and] dangerous to the lungs."

In the United States, federal law has required warnings on cigarette packages since 1966. In the years since then, smoking rates have been sliced in half -- from more than 42 percent Americans who were occasional smokers in the mid-'60s to less than 21 percent now. As for the hardcore who smoke daily, their numbers have dropped to just 12.7 percent, an all-time low. If ever any message reached its intended audience, it is the message that smoking is bad for your health. In fact, smokers tend to overestimate the danger from cigarettes: Surveys show, for example, that smokers put the chances of dying from lung cancer caused by smoking at 40 out of 100. The actual likelihood: between 7 and 13 out of 100.

Smoking's toxic reputation isn't the only thing that has depleted the ranks of American smokers. Cigarettes have never been as highly taxed as they are now, as widely banned, or as deeply stigmatized. Plainly, the last thing the federal government needs to be doing now is rolling out new rules for alerting consumers to the hazards of smoking.

Smoking's toxic reputation isn't the only thing that has depleted the ranks of American smokers. Cigarettes have never been as highly taxed as they are now, as widely banned, or as deeply stigmatized. Plainly, the last thing the federal government needs to be doing now is rolling out new rules for alerting consumers to the hazards of smoking.

That, of course, is just what the feds are doing.

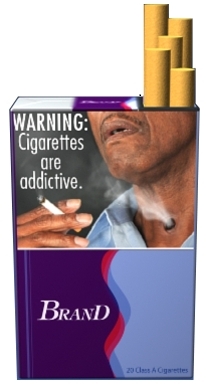

Last week the Food and Drug Administration announced that it will soon require tobacco warning labels to be much bigger -- beginning next fall, they will have to cover half the front and back of each cigarette pack -- and more graphic. Armed with new powers granted by Congress last year, the FDA has designed 36 possible labels, from which nine final choices will be selected.

The proposed warnings, reports The Washington Post, include one "containing an image of a man smoking through a tracheotomy hole in his throat; another depicting a body with a large scar running down the chest; and another showing a man who appears to be suffering a heart attack. Others have images of a corpse in a coffin and one with a toe tag in a morgue, diseased lungs and mouths, and a mother blowing smoke into a baby's face."

Apparently the theory behind such fulsome antismoking imagery is that while everyone knows tobacco is unhealthy, some people need to have their noses rubbed in that fact as pungently and unpleasantly as possible. I don't smoke and never have, and if one of my kids were tempted by cigarettes, I wouldn't hesitate to deploy the diseased-lung or dying-cancer-patient pictures to make sure they realized the potential stakes.

But when did it become the job of the federal government to treat American adults the way mothers and fathers treat children? Is the stomping out of bad personal habits a role we really want to entrust to the Department of Health and Human Services? Washington can't manage to curb its own foul behavior; why would we put it in charge of curbing ours? Few things in modern American life are as ubiquitous as the pressure to stay away from tobacco. Everyone gets the message, which is why the great majority of Americans no longer smokes. The dwindling few who do don't need to be nagged about it by the government of the United States of America.

There will always be some people who smoke, just as there will always be some people who drive recklessly or overeat or drink to excess. Should the manufacturer's sticker on every new car be required to include images of horrible collisions and mangled motorists? Should packages of high-calorie junk food depict rolls of flabby cellulite or a patient undergoing bypass surgery? Should beer and wine bottles be covered with grisly pictures of ruined livers or passed-out drunks?

There will always be some people who smoke, just as there will always be some people who drive recklessly or overeat or drink to excess. Should the manufacturer's sticker on every new car be required to include images of horrible collisions and mangled motorists? Should packages of high-calorie junk food depict rolls of flabby cellulite or a patient undergoing bypass surgery? Should beer and wine bottles be covered with grisly pictures of ruined livers or passed-out drunks?

"The natural progress of things," Jefferson said, "is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground." The nanny-state may make some decisions easier, but it is not compatible with a free society. It isn't Washington's function to wipe your nose just because your nose needs wiping. Of course the functionaries mean well. There always seem to be good reasons for giving them just a little more authority, for agreeing to surrender just a few more personal choices, for letting yourself be treated just a bit more condescendingly. But it comes at a price. Smoking is unhealthy, no question about it. The loss of freedom and self-respect is more hazardous by far.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --