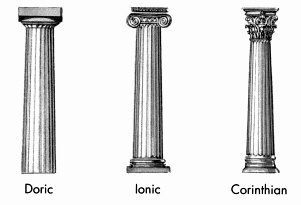

MRS. LEWIS, my sixth-grade social studies teacher, had the gift. A quarter of a century has melted away since I sat in her classroom in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and by now there is little I haven't forgotten about that year in school. But not only do I still remember Mrs. Lewis, and not only do I remember things she taught me, I remember her teaching those things: That the three styles of columns in Greek architecture were Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. That Point Barrow, Alaska, is the northernmost town in the United States. That "huh?" is a sound only pigs should make (She was very firm on that point). That before Ohio became a state, it was part of the Northwest Territory.

A good teacher transmits knowledge to her students; a very good teacher transmits insight and understanding. But some teachers have the rare gift of being able to transmit themselves -- of being able to entwine their own personalities in their students' learning. Many of my schoolteachers were dedicated and skilled. One or two were inspirational. Rarely do thoughts of any of them cross my mind. But my sixth-grade social studies teacher is still, in a way I can't quite explain, a presence. I encounter the word "tundra" and flash on Mrs. Lewis explaining permafrost. I see a photo of the Parthenon and recall, just for a microsecond, where and when it was that I learned: Doric, Ionic, Corinthian.

What makes me think of Mrs. Lewis is "Education Today," a newsletter published by the Massachusetts Department of Education. As a rule, "Education Today" is unreadable glop, full of the dead prose and windy jargon that education bureaucracies pump out by the gallon. (Sample sentence: "Standards for strengthening teaching have been established in the form of principles for effective teaching, and quality professional development opportunities are flourishing statewide, run by the state, colleges and universities, school districts, and local and regional private providers of training." Ugh.)

But the current issue is redeemed by an interview with John Silber, the new chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Education (and outgoing president of Boston University). It is a joy to read Silber's answer to the interviewer's first question: "Is there a ... teacher who had an extraordinary impact on your life?"

There were at least seven, Silber says -- from his mother, Jewell Silber, a second-grade teacher who "drilled and tested" her students relentlessly until each child knew the addition, subtraction, and multiplication tables by heart, to Jerome Zoeller, the demanding high school band leader who ignited in him a lifelong love of music.

John R. Silber |

Across a lifetime of achievement, Silber still remembers Miss Henry, who cared less about stroking her students' self-esteem than about teaching them truth. When Miss Henry assigned a paper on the students' future vocations, Silber, who hoped to be a veterinarian, turned in a detailed report on the profession of animal medicine. It apparently hadn't occurred to him that a boy with his defect -- Silber was born with a stunted arm -- would be unable to handle large animals.

"Miss Henry started laughing," Silber relates, "and said, 'Young people, I want to tell you something funny. I've just read John Silber's booklet on his vocation.... He thinks he's going to become a veterinarian.' And she laughed again.

"Then, looking at me and pointing her bony finger, she said, 'John Silber, I want to tell you something. You're going to do well in your life and be something wonderful. But you aren't ever going to be a veterinarian.' She didn't accept the dogma that you shouldn't tell a child the truth because it might be insensitive.... She didn't destroy my self-esteem. Rather, she advanced my self-knowledge.... And she cast doubt on this notion [of becoming a veterinarian] before I wasted three or four years of my life under an illusion."

Where does their gift come from, the Mrs. Lewises and Miss Henrys? Teachers so effective and memorable that students still quote them 25 and 50 years later -- what is the secret of their success?

Part of it, surely, is love of teaching; part is love of learning. But I wonder if, above all else, what sets apart the unforgettable teachers is the love they have never stopped feeling for their teachers?

One of the brighter lights in the teaching business these days is Will Fitzhugh, founder of The Concord Review, a quarterly journal of essays by high school students of history. On the occasion, earlier this year, of receiving the Kidger Award -- a coveted prize for excellence in teaching -- Fitzhugh told a story about an adult-education course he had taught a few years earlier.

Will Fitzhugh, founder and editor of The Concord Review |

"In one of the classes I had a Japanese couple; the man's English was better than his wife's, and they both worked hard. The night of the last class they brought me a bottle of wine as they were leaving, and then stepped back and bowed.

"It caught me by surprise, and a feeling swept over me that I couldn't immediately label. I am not used to being bowed to. The emotion, when I was able to identify it, was an overpowering feeling of gratitude to my own teachers. It was not a thought, but a feeling of thanksgiving -- for all those who put up with me, who explained things to me, who cared enough about me to teach me."

Great teaching does not come from bigger budgets or smaller classes or tougher unions. Great teaching comes from great teachers -- and perhaps their greatness is this: that they have the gift of gratefulness. They teach to repay the teachers who took pains with them, to discharge a debt that they are fine enough, and wise enough, to acknowledge.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.