My beloved Caleb,

What a comical kid you're becoming! You have grown in so many ways this past year, but the change that tickles me most is the appearance of your sense of humor. Where did it come from? All on your own, you've turned into a little joker. When I call your name -- "Caleb, come here, please!" -- you run and hide, then burst out laughing when I find you. When I dress you in the morning and we get to your socks, I ask for your foot and you stick out your hands. Lately you've perfected a new shtick: You open the cupboard under the

sink, pull out the dishpan, and put it on your head. Mama cracks up every time she sees it.

How did you figure out that some things are funny? For that matter, how do you decide when an old joke has gone flat? A year ago, the words "splish-splash" sent you into a giggling fit. Now that you've reached the ripe old age of two, it takes more than that to amuse you. What will you be like when you're 22? If you take after me, you'll be reciting Monty Python skits from memory. If you take after your mother, you'll be laughing at "Dilbert."

I don't know why you aren't speaking yet, but you certainly aren't having trouble building up your vocabulary. You are forever pointing imperiously to objects around the house, demanding to know what they're called. "Radiator!" we say. "Window!" "Bookcase!" "Plant!" "Another plant!" Sometimes I'm the one doing the quizzing. "Where are the snaps?" I ask as we put on your onesie, and you grab the fasteners on the bottom. "Where's your belly button?" -- and you pull up your shirt to show me. "Where's Jemima?" -- and you run to the cat.

It pleases me to watch you learn so many words, but more gratifying by far is how attached you've become to your books. You are growing up in a home without television, and so you have absorbed next to nothing about the rituals of TV-watching. But our house is chock-a-block with books, and the rituals of reading are already becoming second nature to you.

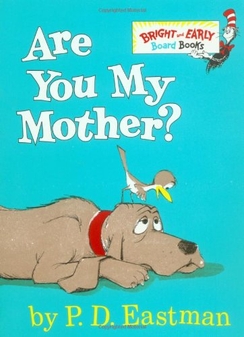

Half a dozen times a day you pull a book from your shelf and march over to the nearest parent, waving it aloft. You've got us well-trained, Caleb: As often as not, we stop what we're doing, snuggle with you on the couch, and begin reading The Little Red Hen or Are You My Mother? or Curious George Rides a Bike. By now you are so familiar with each book -- you must have 20 -- that no matter which one we're reading, we can count on you to turn the page at the right moment.

But even I didn't realize just how aware you are of each individual title and its contents until a few days ago. We were in the kitchen looking out at the snowstorm, and I said

I know it is wet

and the sun is not sunny.

but we can have

lots of good fun that is funny

and you immediately ran to the living room and pulled The Cat in the Hat off the bookshelf. Exactly right! That's the book I was quoting.

As I say, it perplexes me that you still aren't talking. But it's not an entirely bad thing. After all, you have never yet told a lie. You have never

yet used a bad word. You have never yet uttered an insult or hurt anyone's feelings. You have never yet spread malicious gossip.

Once you start talking, you'll feel the urge almost daily to engage in one or another of these forms of wrongful speech. And -- trust me on this, Caleb -- it's an urge fiendishly difficult to resist. But resist you must, and part of my job is to help you learn how. Our tradition places so much emphasis on the importance of avoiding malignant talk. "Who is the man who desires life, and yearns for many days to enjoy good?" asks King David in the 34th Psalm. "Then guard your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking lies."

I know that nothing will influence the words that come out of your mouth more than the words that come out of your parents' mouths. So we are careful about what we say and how we talk in your presence. The Talmud teaches, "What a child says in the street is the words of his father or mother." Eventually you will meet people, maybe even other kids, who resort to crude language or cutting putdowns when they don't get their way. I cannot shield you from such speech forever, but I can try to make sure you never hear it at home.

When I was little, my mother would tell me that every person is born with a fixed quota of words, and when you've used up your allotment, you stop speaking. Her motive, I suspect, was to hush me up -- apparently I wasquite a chatterbox.

Never forget: Every word counts. |

But there is a deeper meaning to your grandmother's remark. A story is told about a Hasidic rebbe who taught that everything that exists in the world has a lesson for mankind. One disciple, sure the rebbe was exaggerating, asked, "And what lesson do we learn from a train?"

"That for being one minute late," the master replied, "you can lose everything."

"And from the telegraph?"

"That you pay for every word."

"And the telephone?"

"That what you say over here, is heard over there."

Never forget, Caleb: Every word counts. And never forget: There is One who hears everything you say.

Don't worry, I'm not rushing you. When you're ready to start talking, you'll start talking. For now, it contents me to see how happy you are. Your days are filled with delight and laughter. May your life be that way always.

All my love,

Papa

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.