SOMEONE did Ray Shamie a kindness when he was 16 years old, and he hasn't forgotten it.

The year was 1937, the depths of the Depression. His father had been killed in a traffic accident and the family was destitute. Shamie, just out of high school, had to go to work so his mother and siblings could eat -- but unemployment was at 25 percent, and there was no work to be had.

"You couldn't get any kind of a job in those days," he was reminiscing the other day from his home in Florida. Fortunately, someone in the neighborhood took pity on the Shamies and used his connections to find young Ray a position. And so the truck driver's son from Queens, an exceptionally bright kid with a talent for math and science, entered the workforce as a busboy, washing dishes and mopping floors at a Horn & Hardart automat. But far from resenting his menial job, he still, 62 years later, remembers with gratitude the man who made it possible.

Who would have given odds in 1937 that the penniless kid with the mop would become a millionaire dozens of times over, the founder of high-tech manufacturing firms that would put thousands of men and women to work, a philanthropist who would share his wealth with uncommon generosity?

I first met Ray Shamie in the spring of 1981, soon after he had decided to run against Edward Kennedy in the US Senate race in Massachusetts the following year. I signed on as research director to the fledgling campaign, even as he warned me that he was naive in the ways of politics. (And, he might have added, in the ways of politicians. "I am not going to walk up to some goddam stranger and try to shake his hand," he told me at an early campaign appearance when I urged him to be more assertive about pressing the flesh.)

Challenging Kennedy was a hopeless long shot, of course, but long shots have always been something of a Shamie specialty.

In the mid-1950s, the head of the manufacturing company he worked for told him his notion of a miniaturized, flexible metal diaphragm would never fly commercially. Shamie quit his job, scraped together every dime he could beg and borrow, and launched his own company, Metal Bellows Co. When medical researchers proposed to fit Shamie's bellows into a drug-dispensing pump that could be implanted in a patient's body, his business colleagues panicked, afraid that the risks of liability would be too great. Undeterred, Shamie began making the pump, ultimately launching a second successful business, Infusaid Corp.

His campaign against Kennedy was less of a success. Still, Shamie earned high points for style and humor, and he succeeded in shaming the senator into meeting him in a televised debate. On Election Day, his message of lower taxes, limited government, greater economic freedom, and support for President Reagan pulled a more-than-respectable 40 percent of the vote.

I was with him two years later when he tried again. Shamie's 1984 Senate campaign was far more serious than the campaign against Kennedy had been. Not because Shamie had changed -- he was still an upbeat conservative, still an admirer of Reagan, still an ardent believer in the power of individual iniative and human liberty. But in 1984 he was taken seriously by the media and the political establishment, especially after he demolished a famous Washington icon, former Attorney General Elliot Richardson, in the Republican primary. He lost the general election to John Kerry, in part because of a sulfurous assault on his character and integrity by The Boston Globe. (Such an attack would be unthinkable today; the Globe's current editors would never allow it.)

Yet even in losing, Shamie won. More than 1.1 million voters cast their ballots for him, and he emerged as the most respected figure in the Massachusetts GOP. His long shot had paid off, albeit not in the way he'd intended.

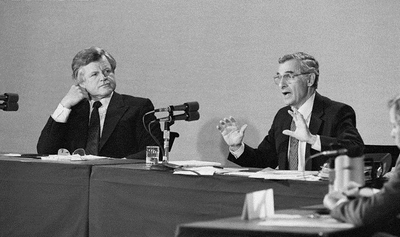

Democratic Senator Edward M. Kennedy listens to his Republican challenger Ray Shamie during their debate at Boston College, October 24, 1982. |

Now he is facing the longest odds of all. Cancer is eating his vital organs. His energy is depleted, he has difficulty breathing, and his weight is plunging. He had planned to spend the summer in his new home on Cape Cod, but he has cancelled his plans to fly up. His doctors don't expect him to see the end of spring.

He hasn't given up hope, exactly -- "Hell, I've been a positive person all my life, about everything," he was saying a few days ago -- but he also hasn't stopped being a realist. The man who once quoted to me by heart Brutus's famous "There is a tide in the affairs of men" admonition from Julius Caesar knows better than to count on a remission.

In a sense, it was his realism that led Shamie into politics in the first place. He believed that most voters were like him -- that if given accurate information, they would choose the right leaders. It saddened him to discover the truth -- that most ballots are not cast on the basis of ideas and analysis, but for irrational reasons: emotion, blind party loyalty, even ethnic affiliation. He still talks about the woman who approached his wife in a supermarket during the 1982 campaign. "I really like what your husband says, I like what he stands for," the woman told her. "But I have to vote for Ted Kennedy. He came to my daughter's graduation."

Americans unhappy with politics-as-usual often lament: "Why don't more decent people go into politics?" It will soon be time to bid farewell to one decent man who did.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.