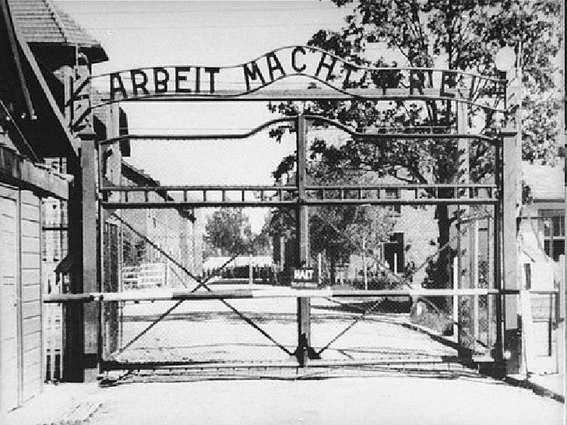

BY THE TIME the Soviet Army reached Auschwitz on Jan. 27, 1945 -- 60 years ago this week -- my father was no longer there. Ten days earlier, the Nazis had evacuated about 67,000 of the death camp's inmates, dispatching them on brutal forced marches to the west. My father, then 19, was in a group sent into Austria. He ended up at the concentration camp in Ebensee, near Mauthausen. Liberation there didn't come until May 9, with the arrival of US soldiers from the 80th Infantry Division.

My father had entered Auschwitz the previous spring, together with his parents, his two brothers, and two of his three sisters. They, too, were gone by the time the camp was liberated. Unlike my father, they didn't leave on foot. They "left" through the chimney. For the overwhelming majority of the more than 1.1 million Jews who were sent to Auschwitz, there was no other exit.

Jews were not the only victims. Nearly 75,000 Poles, more than 20,000 Gypsies, 15,000 Soviets, and 10,000 members of other nationalities were murdered at Auschwitz as well. The Nazis first used the camp, in fact, as a prison for Polish dissidents, and Birkenau, the huge 1941 addition that became the main Auschwitz killing center, was originally designed to hold Soviet POWs.

But beginning in the spring of 1942, Auschwitz became first and foremost a slaughterhouse for Jews. From every corner of Europe, Jews were sent there – from France in the west to Ukraine in the east, from as far north as Norway and as far south as Greece. Many, like my father and two of his siblings, were forced into slave labor, in the expectation that the ghastly conditions and starvation rations would kill them soon enough. But most of the Jews entering Auschwitz – like my father's parents and his youngest brother and sister – were murdered as soon as they arrived.

Auschwitz was a vast factory of death, the site of the greatest mass murder in recorded history. Even now, two generations later, it is almost impossible to grasp the scale on which the Nazis committed homicide there. It is suggested by a detail: From 1942 to 1944, the train platform in Birkenau was the busiest railway station in Europe. It held that distinction despite the fact that, unlike every other train station in the world, it saw only arrivals. No passengers ever left.

But Auschwitz was not only a place of murder. It was also a place of theft.

Jews were robbed of everything they owned – the luggage they came with, the clothes on their backs, the hair on their heads, even the gold in their teeth. The stolen goods were stored in 35 warehouses, where they were sorted and packed for shipment to Germany. Before fleeing in January 1945, the Nazis burned 29 of the warehouses, but in just the six that remained, the Soviets found 348,820 men's suits, 836,255 dresses, and 43,525 pairs of shoes. There were seven trainloads of bedding, waiting to be shipped. And 7.7 tons of human hair. And that was merely what remained at the very end.

The very worst thing about Auschwitz was -- what? The staggering death toll? The gas chambers disguised as showers, in which thousands of naked Jews went daily to agonizing deaths? The endless cruelty and torture? The diseases that ravaged those the Nazis didn't kill first?

Was it the inhuman medical experiments carried out by doctors like Josef Mengele, such as the deliberate destruction of healthy organs, or the sadistic abuse of twins and dwarfs? Was it the willing exploitation of Jewish slave labor by German corporations? The tens of thousands of murdered children and babies?

No.

The very worst thing about Auschwitz is that, for all its evil immensity, it was only a fraction of the total. Even if it had never been built, the Holocaust would still have been a crime without parallel in human history. It would still have been something so monstrous that a new word – genocide – would have had to be coined to encompass it. Never before and never since has a government made the murder of an entire people its central aim. And never before or since has a government turned human slaughter into an international industry, complete with facilities for transportation, selection, murder, incineration. And none of it as a means to an end, but as an end in itself: The reason for wiping out the Jews was so that the Jews would be wiped out.

In the end, 6 million of them were killed. But only one-sixth died at Auschwitz.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.