FOR THOSE with the good fortune to be both American and Jewish, this is a two-holiday weekend. Chanukah follows almost upon the heels of Thanksgiving. The menorah's first candle, ushering in the eight-day festival, will be lit Sunday evening.

FOR THOSE with the good fortune to be both American and Jewish, this is a two-holiday weekend. Chanukah follows almost upon the heels of Thanksgiving. The menorah's first candle, ushering in the eight-day festival, will be lit Sunday evening.

Too bad Chanukah doesn't arrive this close to Thanksgiving every year. Although they commemorate historical events nearly 1,800 years apart, the two holidays resonate deeply with each other. Inasmuch as we seem poised on the edge of a national debate over the place of prayer and God in our public institutions, this might be an apt moment to consider how much Chanukah and Thanksgiving have in common.

Chanukah celebrates the Jewish victory over the Syrian-Greek tyrant Antiochus IV, who sought to impose his Hellenistic ideology throughout the Seleucid empire. He succeeded nearly everywhere. But in Judea, religious Jews balked. Faithful to their Torah and their one God, they rejected Hellenism, with its network of pagan gods, its cult of the body and its obsession with public games.

Their resistance was met with horrifying cruelty. Antiochus set about to destroy Judaism. He abolished Jewish law. He banned observance of the Sabbath and the study of Torah, two pillars of Jewish life. He dispatched soldiers to set up altars across the country and forced Jewish leaders to sacrifice pigs upon them. He installed a statue of Zeus in the Temple at Jerusalem; those who would not worship it were killed. Among the many martyrs were the seven sons of Hannah, each of whom refused to bow to the idol. One by one, they were slaughtered before their mother's eyes.

In 167 BC, the Jewish revolt began. The aged priest Mattathias and his five sons, led by Judah Maccabee, launched a guerrilla war against the vastly more powerful Syrian-Greeks. Though impossibly outnumbered, they won miraculous victories. In 164 BC, the Maccabees recaptured the desecrated Temple, which they cleansed and purified and rededicated to God. The menorah -- the candelabrum symbolizing the divine presence -- was rekindled.

The fighting raged on. Not for another 22 years would the Jews regain full political sovereignty in their land. But to mark that turning point of religious renewal, the day the Temple was restored and the threat to Jewish law repelled, a new holiday was instituted. It was called "Chanukah" -- Hebrew for "dedication."

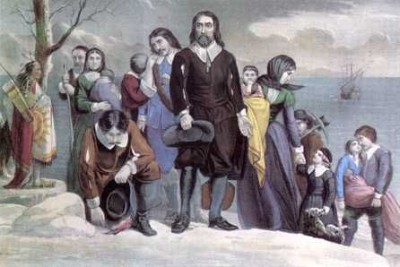

Eighteen centuries later, another small group of believers marked their own rededication, and gave thanks for their survival in the face of terrible devastation.

The Pilgrims who gathered for the first Thanksgiving feast in 1621 had little enough to be grateful for. Puritan separatists from East Anglia, they had been severely persecuted by the established Church of England. In 1608, desperate to live in a land where they could worship as they thought right, the separatists made their way to Holland, then as now a tolerant place.

But life in Holland was difficult, too. There were many fears, above all that Holland would be conquered by Spain. That would bring the Inquisition and terrors even worse than those of King James.

And so the little band of believers took a step fraught with profound gravity and risk: They sailed to America. It was a nearly suicidal endeavor. Published guides at the time advised would-be voyagers to the New World: "First, make thy will."

And so the little band of believers took a step fraught with profound gravity and risk: They sailed to America. It was a nearly suicidal endeavor. Published guides at the time advised would-be voyagers to the New World: "First, make thy will."

On Dec. 26, 1620, the Pilgrims waded ashore at Plymouth. It was winter. They were lost in the wilds of Massachusetts with little food and no shelter, far from the Virginia colony they had been aiming for.

"That which was most sad and lamentable," their governor, William Bradford, would later record, "was that in two or three months' time, half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and lacking houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases which this long voyage and their inaccommodate condition had brought upon them. There died sometimes two or three of a day."

To be with their God, to worship in peace, these people had uprooted their lives, forsaken everything they had known, and watched half of their small group -- husbands, wives, children -- die of sickness and starvation.

Like Job, the Pilgrims suffered every loss imaginable -- except the loss of faith. And so they could sit down a year later, the few who survived, and proclaim a day of Thanksgiving. Or as the Maccabees might have put it, a day of rededication.

Plymouth was not the first settlement in the New World; Jamestown, in Virginia, preceded it by 13 years, and the Spanish had already been in Mexico for a century. But the Pilgrims built the first colony founded on a principle: the right to worship freely. That is why the landing at Plymouth marks the real origin of American democracy.

The victory of the Maccabees and the arrival of the Mayflower were episodes of great political moment. But Chanukah and Thanksgiving are not about politics. Nor are they about turkey or football or presents.

We may have secularized them and materialized them, but underneath the modern trappings, these holidays are really about religion. Each is rooted in the triumph of belief over persecution. Each draws its power from the courage of pious men and women who endured terrible suffering for their devotion to God. And each is a reminder, as we head into the blackest nights of winter, that nothing can overcome the darkness like the light of faith.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)