"AT LEAST he should apologize," Elie Wiesel is saying. "He should apologize for the past. The past cannot be erased. At least let him come forward and say: 'I apologize for having given the order to kill Jewish children at Ma'alot, and Jewish civilians in the street, and all the other innocent people.' "

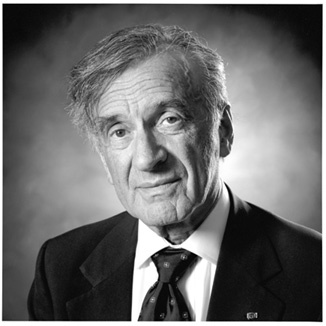

The 1986 Nobel laureate for peace is struggling with the news that Yasser Arafat will be one of the 1994 Nobel laureates for peace. Wiesel, a survivor of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, a tireless champion of decency and human dignity, is this generation's most renowned eyewitness to the massacre of Jews. Arafat, the head of the PLO, the very archetype of modern terrorism, is this generation's most infamous perpetrator of the massacre of Jews.

"It's a very painful thing," Wiesel is saying. "All of a sudden I'm in the same group as he is. Imagine! We both have memberships, he and I."

Arafat, along with Israel's Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, is being honored for signing last year's Israel-PLO peace accords. And for "that specific act" alone, the chairman of the Nobel Committee, Francis Sejerstad, underscored in a press conference last week.

But does one "specific act" wipe away the remembrance of the PLO's innumerable victims? The 27 children killed in the schoolhouse at Ma'alot? The 11 Israeli athletes butchered at the 1972 Olympics?

Does a White House ceremony, does a public handshake, atone for the civilians slaughtered in the airports of Rome, Vienna and Tel Aviv? Does it make up for the recipients of the PLO's letter bombs? For the worshipers at the Istanbul synagogue who were machine-gunned by Arafat's men? For Leon Klinghoffer, the passenger on the cruise ship Achille Lauro who was shot in his wheelchair and thrown overboard? For the slain US ambassador to Sudan, Cleo Noel, and his deputy, George Moore?

"It is hard to swallow," Wiesel is telling a caller, his voice perplexed with sadness. "I know the members of the Nobel Committee. Of course they hope some good will come out of their decision. I don't want to criticize them. I understand their logic, or at least their rationale -- saying: True, this man has a past, but look what he has done recently.

"But I believe in memory. I believe you cannot just erase memory. And this man, at least for 25 years, has been the leader of a terrorist organization that was created to kill Jews. The man has done so much harm, has shed so much blood, has ordered others to shed so much blood -- and all of a sudden he becomes a tzaddik" -- Hebrew for a saintly man - "a Nobel laureate in peace? In peace?"

Nobel peace prizes come in two varieties. Some years the award goes to humanitarians of exceptional standing, moral giants like Mother Teresa -- men and women who rise above the bickering and bigotry and banality for which our species is notorious. Other years the prize is given to reward or encourage politicians who advance the difficult cause of what Alfred Nobel, in his will, called "fraternity between nations."

This year's award, clearly, is of the second type, and such awards are easy to second-guess. Fine. Let us be fair. Let us grant the Nobel Committee's good intentions. Let us grant that Middle East diplomacy, like the making of laws and sausage, is not an appetizing business. Let us grant that the peace prize will inevitably go, at times, to public officials whose records are blemished -- Mikhail Gorbachev, Nelson Mandela, F.W. de Klerk, Menachem Begin, Anwar Sadat.

Even so, where is the "fraternity" that Arafat is helping to build?

Articles 9 and 19 of the Palestine National Covenant, which call for the liquidation of Israel by violence, remain in force, despite Arafat's signed guarantee that they would be repealed. Dozens of terrorist attacks have been attempted or carried out by PLO factions since the signing of the accords. Far from denouncing terror, Arafat has reaffirmed his own rejectionism. "Jihad will continue," he told a Muslim audience earlier this year, using the Arabic term for religious war. "Now our main battle is for Jerusalem."

Arafat's is not the face of fraternity between nations. For a quarter-century or more, it has been the face of random terror, of bombings and hijackings, of innocent victims chosen because they were innocent. How surreal to imagine Arafat, who fashioned a career out of death and devastation, in the same company as Elie Wiesel. As Martin Luther King. Albert Schweitzer. Mother Teresa. The Dalai Lama. Could anything capture more utterly the ethical anarchy and moral obtuseness of our time?

"But this is not new," Wiesel sighs. "Yes, moral values are going through a crisis. But when Arafat came to the United Nations wearing a gun holster" -- which he did in 1974 -- "what was that? Wasn't that also moral decadence in an international organization?

"I am afraid that as we come closer to the end of the century, to the millenium, there is a growing chaos. In Jewish tradition, we believe that the worst punishment is chaos. Chaos means that good and evil have the same potency, wear the same mask. That they are equivalent.

"What can we do? We try to speak, we try to educate -- I believe in education more than anything in the world. But I am often moved to despair when I see what is happening."

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Join the Fans of Jeff Jacoby on Facebook.