ANYBODY OUT THERE who doesn't know by now that Mitt Romney, the Republicans' endorsed Senate candidate, is a faithful Mormon? Anybody who doesn't know that Ted Kennedy is a -- how would one put it? faithless? unfaithful? -- Catholic? Anybody who does know the religion of John Lakian, the other Republican in the race? (Answer: Armenian Apostolic.)

In an ideal world, religion would be private and politics would be public, and never the twain would meet. Or maybe that wouldn't be so ideal. The Founders of the Republic were pretty adamant that democratic politics grow unhealthy and sterile if they aren't fed by religious values.

"Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity," insisted President Washington -- hardly a holy roller -- in his Farewell Address, "religion and morality are indispensable." John Adams warned that "our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other." Even Thomas Jefferson, that skeptical Deist, agreed.

The Founders notwithstanding, it has been a long time since candidates lost political points for being insufficiently reverent. Pundits and journalists, themselves more apt to devote Sunday mornings to the chat shows than to church, would be embarrassed to grill a politician on why he doesn't worship more regularly. Republicans do not make political hay out of the fact that Kennedy's fidelity to his religion is so . . . lax.

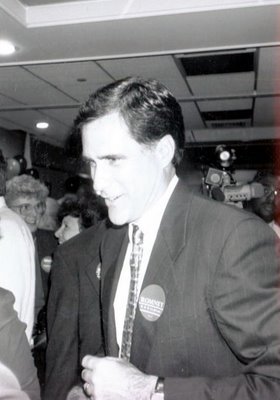

GOP Senate candidate Mitt Romney is a Mormon. So what? |

The high-minded cliché is that a candidate's faith is immaterial to his fitness for office. We tell ourselves that we don't vote for or against people because of the religion they profess. We quote John F. Kennedy's 1960 speech, addressing the "Catholic issue," to the Houston ministers: "If this election is decided on the basis that 40 million Americans lost their chance of being president on the day they were baptized, then it is the whole nation that will be the loser. . ."

In 1994, no one dares suggest that Romney, by virtue of being Mormon, doesn't belong in the Senate. (Though one liberal Democrat, activist Vincent McCarthy, has come close to naked anti-Mormon bigotry: "I have always found it a delicious irony," he said in July, "that a church founded on polygamy is so sanctimonious about fornication and homosexuality.")

Rather, the argument being nudged along, both by Romney's foes and by reporters sniffing into his church activities, goes like this:

(1) The Mormon views on topics X, Y and Z are well defined; Romney is a devout Mormon; ergo his views on X, Y and Z are likely to be shaped by his religious beliefs -- which makes those beliefs politically relevant. (2) On the other hand, if his public positions on X, Y and Z are not the same as his private religious beliefs -- and on some issues, such as gay rights, they are not -- then the discrepancy is politically relevant. (3) And if in his dealings with other Mormons he has pushed positions he claims to reject as a candidate, that too is relevant, for it speaks to his credibility.

The problem with that logic is that the only candidate it is being applied to is Mitt Romney.

Robert Massie is a Democrat running for lieutenant governor. He is also an Episcopalian minister. Yet Massie's religious beliefs have been the focus of exactly zero political stories. Do his political stands mirror church doctrine? Are there issues on which he espouses one view while campaigning, and a different view in the sanctuary? Nobody asks. Nobody cares. Why?

One reason is that Massie is a liberal.

To a press corps that is predominantly liberal itself, it is exclusively the "religious Right" that invites suspicion. In a lot of newsrooms, the link between religion and politics is of interest only when the Christian Coalition recruits candidates for office, or Rev. Pat Robertson mounts a campaign, or the Vatican mobilizes against abortion.

Since Massie is running from the left, he is vaccinated against the media's distrust of religious figures, much as Rev. Robert F. Drinan, the leftwing former congressman, was, or Rev. Jesse Jackson, or Haiti's Jean-Bertrand Aristide. But Romney is not liberal, nor is his church. So his religious background comes up in debates. He's quizzed on it in editorial meetings. Soon any story that says "Romney" must also say "Mormon."

Which is not like saying "Episcopalian." Rev. Massie's religious ties draw no attention because he is one of "God's frozen people" (as some Episcopalians humorously describe themselves), trained in a faith less exotic to most Americans than a washing machine. But there aren't many Mormons hereabouts, and if anything makes Massachusetts curl its lip, it is people with nonconformist religions. This is the state that used to hang Quakers on Boston Common and send "heretics" into exile. In 370 years of Massachusetts politics, just one Jew has ever won statewide office.

Intended or not, the drip-drip-drip of stories about Romney's Mormonism aggravates the old Massachusetts prejudice against people who worship differently. Maybe Lakian and Kennedy, whose polls tell them that the "Mormon" label is a political negative, are happy to exploit that prejudice. But journalists cannot pretend not to understand what they are doing each time they work the M-word into a story.

If we're going to put the Mormon Church under a microscope, I have a suggestion: Let's spend less time studying its theology, and more time admiring the people it turns out. Mormons tend to be honest, moral, upright, hardworking, faithful to their families and so clean they squeak. That description sounds awfully like one of the candidates in the US Senate race, and I don't mean the one named Kennedy.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.)

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.