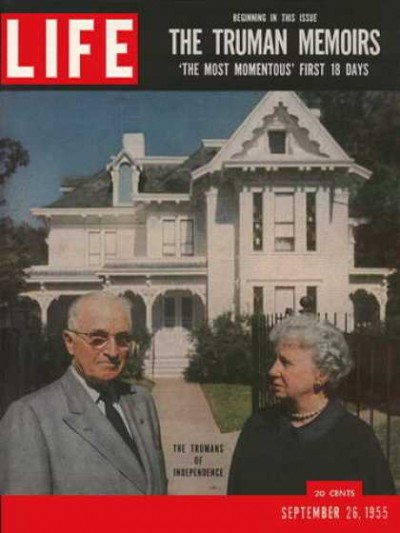

WHEN HARRY TRUMAN left the White House in 1953, historian David McCullough records, "he had no income or support of any kind from the federal government other than his Army pension of $112.56 a month. He was provided with no government funds for secretarial help or office space, not a penny of expense money." To tide him over for the transition back to private life, Truman had to take out a bank loan. One of the reasons he and his wife moved back into their far-from-elegant old house in Independence, Mo., "was that financially they had little other choice."

Nevertheless, Truman refused to cash in on his celebrity and influence as a former president. He turned down lucrative offers, such as the one from a Florida real estate developer inviting him to become "chairman, officer, or stockholder, at a figure of not less than $100,000." He wouldn't make commercial endorsements, accept "consulting" fees, or engage in lobbying. He wouldn't even take the free car that Toyota offered him as a gesture of improved Japanese-American relations.

"I could never lend myself to any transaction, however respectable," Truman later wrote, "that would commercialize on the prestige and dignity of the office of the Presidency." He did sell the rights to his memoirs for a handsome sum to Life magazine. But he turned down every other enticement to trade on his former position for private gain.

Half a century later, Truman's rectitude seems as quaint and obsolete as George Washington's wooden teeth.

Half a century later, Truman's rectitude seems as quaint and obsolete as George Washington's wooden teeth.

We learned last week that in the six years since Bill Clinton left office, he has pocketed a staggering $40 million in speaking fees. Tirelessly working the lecture circuit, he has delivered hundreds of speeches, often at a price of $150,000 and up. Two-thirds of his speaking money has come from foreign sources, according to The Washington Post, including "Saudi Arabia's Dabbagh investment firm, which paid $600,000 for two speeches, and China's JingJi Real Estate Development Group, run by a local Communist Party official, which paid $200,000 for a speech."

Clinton's spokesman says that a careful vetting process precedes every speech, but the former president has accepted invitations from organizers with less than pristine ethical records. In 2005, the Post reports, he received $650,000 for two lectures he gave for The Power Within, a motivational-speech company in Canada whose founder "was convicted of stock fraud and ... barred for life from the brokerage business." He delivered a $150,000 speech to Serono International, a Swiss biotechnology giant, while it was under investigation for giveaways to doctors who unnecessarily prescribed its drug. Serono later pleaded guilty to conspiracy and paid $704 million in penalties.

The scale of Clinton's post-White House earnings is known only because financial-disclosure rules require his wife, Senator Hillary Clinton, to report them. (They don't include the additional millions his speeches have raised for the William J. Clinton Foundation, his nonprofit charity.) But he is hardly the only former president to leverage the prestige of the presidency for big bucks.

This shabby practice began with Gerald Ford, who accepted high-paying board memberships at companies like 20th Century-Fox, Primerica, and American Express. Ronald Reagan was paid $2 million to deliver two 20-minute speeches in Japan shortly after leaving the White House in 1989, and both George H. W. Bush and Jimmy Carter have traveled widely to lecture for pay.

The elder Bush in particular seems to be Clinton's model. The Wall Street Journal reported a decade ago that "in the four years since he left office, Mr. Bush, already a wealthy man, has earned millions of dollars speaking publicly." Charging $80,000 to $100,000 per appearance, "Bush generally restricts himself to giving speeches and rubbing shoulders with corporate executives and high-level government officials."

Such post-presidential avarice might be more understandable if presidents were still leaving office the way Truman did, with nothing from the taxpayers but a fond farewell. But that hasn't been the case since the passage of the Former Presidents Act in 1958.

Today former presidents receive a lavish pension -- currently $186,000, but it increases yearly -- payable as soon as they depart the White House, regardless of their age. In addition, former chief executives are granted hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual staff, office, and travel allowances. For fiscal year 2007, Clinton will receive approximately $1.16 million from the US Treasury -- his telephone stipend alone will come to $77,000. All former presidents are also entitled to free, round-the-clock Secret Service protection for themselves and their families. The cost of providing security for previous First Families is estimated at $20 million a year.

According to the National Taxpayers Union, Clinton will reap a lifetime pension payout of more than $7 million, assuming a normal lifespan. The senior George Bush can expect to bank more than $3 million; for Carter, the total will likely top $4 million. Clearly the age when former presidents could find themselves in dire financial straits is long gone. Sadly, so is the sense of integrity and propriety that once kept men like Truman from devoting their post-presidency to money-grubbing. It wasn't only the buck that stopped with the 33rd president. The avarice did, too.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter