TO JUSTIFY his endless calls for more and higher tariffs, President Trump likes to point to William McKinley, the nation's 25th chief executive. He cited him in his inaugural address last month, declaring that the Ohio Republican "made our country very rich through tariffs."

But as historians — even conservative Republican historians — have pointed out, McKinley gradually turned against tariffs over the course of his career. By the time he became president, he had abandoned his former protectionism and asked Congress for the power to cut tariffs on foreign imports in order to induce other countries to lower their tariffs on American goods. In the words of Karl Rove, a longtime Republican strategist and the author of a well-regarded biography of McKinley: "On tariffs, the president gets McKinley wrong." Rove notes that after McKinley's inauguration in March 1897, "the new president grabbed the chance to lower trade barriers" — exactly the opposite of the Trump approach.

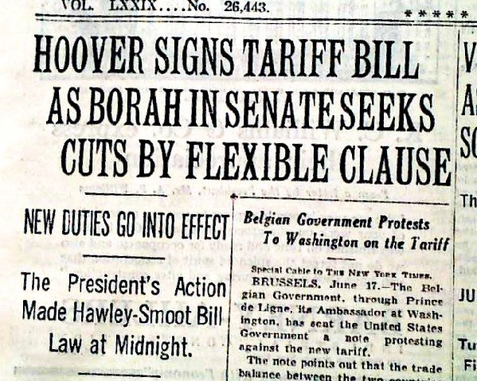

The Republican predecessor Trump more closely resembles when it comes to trade policy is Herbert Hoover, who in June 1930 signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act into law. Hoover had run for president on a platform of raising agricultural tariffs and felt bound to sign the bill passed by Congress — even though its protectionism went much farther than he had intended. More than 1,000 economists signed a petition urging Hoover to veto the bill, which raised taxes by more than 40 percent on some 20,000 imported goods. The president himself acknowledged privately that the higher duties were "vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious," but approved it just the same.

The effect of the new law was wholly predictable: It turbocharged a trade war, drove many prices higher, reduced American imports and exports by two-thirds, undermined foreign relations, and made the Great Depression even worse than it already was. Republicans paid a stiff price for their economic benightedness, losing not only the White House to Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 election, but their large majorities in the House and Senate as well. Among the defeated were Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative Willis Hawley of Oregon, the law's lead sponsors.

Though more than 1,000 economists urged him not to, President Hoover signed a 1930 bill sharply raising tariffs. The result was a ruinous trade war. |

FDR sharply denounced the Smoot-Hawley Tariff during the 1932 campaign. As president he would promote any number of terrible economic policies, from a massive increase in government spending to forcibly increasing prices to the imposition of industry "codes" that curtailed production and suppressed competition. But about the harmful impacts of the trade war set in motion under Hoover, his insights were absolutely on point. During one speech in Seattle, he cogently explained how Hoover's signature on Smoot and Hawley's bill had set the nation on the "road to ruin."

The sweeping new tariffs prompted at least 40 other countries to retaliate with higher tariffs on American exports, Roosevelt said. For example, he told his Washington state audience,

our next-door neighbor, Canada, imposed retaliatory tariffs on your peaches, so that their tariff is now higher than the freight rates to Canada. And there is a retaliatory tariff on asparagus, and on other vegetables and other fruits, so high that practically none of your agricultural product can be sold to your logical customers, your neighbors across the border. The market for your surplus is destroyed and thereby fair prices for your whole crop are made impossible....

Retaliatory tariffs on condensed milk have closed milk condensaries on the Northern Pacific Coast. Companies have sold their cows. Let us see the effect of that. As you and I know, that cuts off the market for the hay crops raised by the farmers. That is a good example of the fact, the undeniable, undisputed fact of the interdependence of industry and agriculture.... In short, because we have built unjust tariff walls ourselves, other countries are now using our own poison against us.

One Roosevelt Democrat who would later become a Republican — Ronald Reagan — absorbed the lesson that protectionism leads to disaster and took it with him when he switched parties. Reagan's influence helped turn the GOP into a party of philosophical free traders. The Gipper often decried trade warriors who worship high tariffs.

"Today protectionism is being used by some American politicians as a cheap form of nationalism, a fig leaf for those unwilling to maintain America's military strength and who lack the resolve to stand up to real enemies — countries that would use violence against us or our allies," Reagan said in a 1988 address, parts of which sound like it was written in response to the Trump administration's tariff follies.

"Our peaceful trading partners are not our enemies; they are our allies," Reagan continued. "We should beware of the demagogues who are ready to declare a trade war against our friends — weakening our economy, our national security, and the entire free world — all while cynically waving the American flag. The expansion of the international economy is not a foreign invasion; it is an American triumph, one we worked hard to achieve, and something central to our vision of a peaceful and prosperous world of freedom."

To mark Reagan's birthday on Feb. 6, the White House released a presidential message celebrating the "common sense political vision" of the nation's 40th president and noting that his vision "usher[ed] in a new era of prosperity and peace at home and abroad." That is indeed what Reaganism accomplished. If only Trump had some of the economic and political wisdom that made Reagan's achievements possible.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Thy neighbor's sidewalk

My wife and I have a dilemma. I'd like to tell you about it.

Our doorbell rang late Sunday morning, and I had a feeling it would be our neighbor Tom. Several inches of snow had fallen overnight and when my wife went out to shovel our sidewalk and the end of our driveway, she took a few extra minutes to shovel Tom's sidewalk too.

Shovel thy neighbor's sidewalk ... or not? |

My wife has been the designated shoveler in our home for a long time — ever since we discovered, when I reached my 50s, that three hoists of a snow shovel would throw my lower back into spasms of pain that might last for days. Lucky for me, I married someone who is not only good at dealing with snow (she grew up near the Canadian border in northern New York State, where heavy snowfalls are taken for granted) but for whom shoveling is an invigorating form of exercise. Normally she goes to the gym on Sunday mornings; this time she stayed home and scooped snow.

When our younger son is at home during a snowfall, we'll send him out to do the shoveling — and remind him to clear our neighbor's short sidewalk as well. But he often goes away on weekends, so he wasn't here Sunday.

Tom, who is in his 80s and declining health, is no longer able to shovel for himself. But back in the day, he would clear his sidewalk and driveway with a snowblower — and if we hadn't gotten to it yet, he would also do ours. When we would thank him, he would wave it off. With the snowblower, he'd say, removing our snow was no trouble at all. Besides, he would tell my wife, he liked having us and our boys next door. And what are neighbors for, if not to lend each other a hand?

Now here's the dilemma: Tom says he doesn't want my wife (or me, for that matter) to shovel his walk. When our son does his shoveling, Tom is delighted and eager to show his appreciation with a generous tip, ignoring our protests that we want our kids to be neighborly and helpful for its own sake, not for a reward. But once he realized that it was my wife who has been doing the shoveling this winter, he has been scolding us and saying he doesn't want her to do it — not because she's a woman, as we at first suspected, but because he thinks she's too old for such strenuous activity. (She's 15 years younger than he is.) When she points out that she likes the exercise and is already shoveling in front of our house, he sputters: "Well, I can't do anything about that."

So when the doorbell rang Sunday, I knew it would be Tom coming to protest his cleaned sidewalk. And as if that weren't bad enough, he insisted on paying my wife for her good deed. After he left, she showed me the $100 bill he had pressed into her hand and said she was going to figure out a way to return it to him without his finding out. Then we decided to donate it instead to a charity in his honor. Accordingly, St. Mary of the Assumption Elementary School, which is around the corner from us, received a $100 donation on Sunday, along with a note saying that it was in honor of their nearby parishioner (Tom and his family are faithful Catholics).

So, readers, my question for you is: Did we do the right thing? Tom's sidewalk needs to be shoveled and, after all these years of keeping an eye out for each other, it would feel wrong to just leave the snow for him to deal with. On the other hand, if someone like Tom insists that he doesn't want a neighbor's help, however modest that help might be, it feels wrong to override his wishes and perhaps bruise his pride. On the other other hand, if he has no problem with our son shoveling his walk, it seems fair to assume that his pride isn't all that fragile.

My wife and I try to live up to the injunction of "Love thy neighbor" and we have been fortunate in having neighbors like Tom, who are friendly and considerate. But in a case like this, what are we enjoined to do? To shovel our neighbor's snow, or to leave it alone? If you have thoughts, please share them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "How to spend the surplus," Feb. 3, 2000:

Spending by the federal government has been growing at roughly 5 percent a year. Federal revenues have been growing almost twice as fast. The result is a budget surplus estimated at $170 billion this year — and as much as $4 trillion over the next decade.

This geyser of cash has awakened something unheard in America for generations: serious talk of erasing the nation's public debt.... During his State of the Union speech, Bill Clinton announced, to wild applause, "We are doing something that would have seemed unimaginable seven years ago. We are actually paying down the national debt. If we stay on this path, we can pay down the debt entirely in 13 years and make America debt-free for the first time since Andrew Jackson was president."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Thy firmness makes my circle just, / And makes me end where I begun." — John Donne, "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning" (1611)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read something different? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly newsletter.