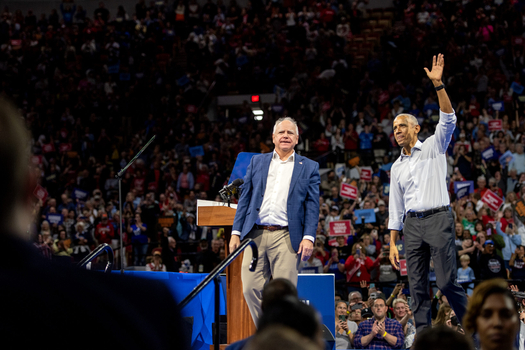

FORMER PRESIDENT Barack Obama, campaigning with vice presidential nominee Tim Walz at a Wisconsin rally last week, strongly urged supporters in the battleground state to take advantage of early voting and cast ballots for the Democratic ticket as soon as possible.

"Even one or two extra votes per precinct will be enough to win this thing and send Kamala to the White House," said Obama, who is, as the Associated Press noted, the only president to carry Wisconsin by more than a percentage point in the past six elections. "If you haven't voted yet, I won't be offended if you just walk out right now," he told the crowd. "Go vote! Go do it!"

With the election just days away, Obama went on the attack against the Republican nominee.

"Wisconsin, we do not need to see what an older, loonier Donald Trump looks like with no guardrails," he said. I agree with him there. Trump's character is atrocious and his influence on American politics has been poisonous. As president, he presided over some fine achievements — meaningful tax cuts, the Abraham Accords, repeal of the Obamacare mandate, abrogation of the Iran nuclear deal — but his presidency was also a freak show of insults, narcissism, shattered civic norms, and false accusations, culminating in the violent US Capitol mayhem of Jan. 6, 2021.

So when Obama warns against another Trump presidency, he gets no argument from me.

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz and former President Barack Obama appeared at a campaign rally in Madison, Wis. |

But Obama also claimed to be mystified by the polarized, partisan acrimony that has come to dominate American politics. "There are times," he told the crowd in Wisconsin, "where I don't understand how we got so toxic and just so divided and so bitter."

Really? A glance in the mirror might jog his memory.

Because well before there was Trump, there was Obama. And Obama's presidency was the most polarizing in modern history up to that time.

Obama himself acknowledged as much in his 2016 State of the Union address, as he was beginning his eighth year in the White House.

One of the "few regrets" of his presidency, he told the assembled members of Congress, was "that the rancor and suspicion between the parties has gotten worse instead of better." Were he endowed with "the gifts of Lincoln or Roosevelt," he remarked, he could have done more to bridge the partisan divide.

Four years earlier, when he was nearing the end of his first term and running for a second, he had said much the same thing.

"I'm the first one to confess that the spirit that I brought to Washington, that I wanted to see instituted, where we weren't constantly in a political slugfest . . . I haven't fully accomplished that," Obama told "60 Minutes" in September 2012. "My biggest disappointment is that we haven't changed the tone in Washington as much as I would have liked." He even acknowledged, when pressed by the CBS interviewer, that he was to blame for some of the ill will: "As president, I bear responsibility for everything to some degree."

To be sure, the nation's politics grew even more virulent and divided once Trump came on the scene. But give Trump this much: He never claimed to be a healer. Obama did, over and over.

From the moment he stepped on the national stage, Obama committed himself to elevating the tone of public discourse, to bringing red and blue America together, to leading the nation into a new era of political goodwill. A key reason he was running for president, he told Boston Globe editors and reporters in January 2008, was to repair a political system that had gotten "stuck in this deeply polarized pattern." He promised that there would be reconciliation and that it would start with him: "I'm not going to demonize you because you disagree with me," he said.

Obama's pledge to be a unifier was the central theme of his presidential campaign. It went to the heart of his political appeal and led countless voters to invest great hope in the prospect of an Obama presidency.

But it never happened. And it wasn't only Republicans who noticed.

"Rather than being a unifier, Mr. Obama has divided America on the basis of race, class, and partisanship," wrote two Democratic pollsters, Patrick Caddell and Douglas Schoen, in July 2010. "Moreover, his cynical approach to governance has encouraged his allies to pursue a similar strategy of racially divisive politics on his behalf."

Obama took to personalizing his political criticisms with ad hominem attacks that — in those days — were not normal fare from presidents. When the Supreme Court issued its ruling in the Citizens United case, Obama attacked the justices to their faces as they attended his address to a joint session of Congress. During the debate over healthcare, as The Wall Street Journal noted, "Obama did not merely disagree with opponents but accused them of being 'cynical and irresponsible,' spreading 'misinformation,' and making 'bogus,' 'wild,' or 'false' claims through 'demagoguery and distortion.' "

By the time of his 2012 reelection campaign against Mitt Romney, Obama had abandoned the politics of hope and unity. He focused instead on winning a second term by any means necessary. Even left-leaning media outlets were struck by his harshness.

"Obama and his top campaign aides have engaged far more frequently in character attacks and personal insults than the Romney campaign," Politico reported in 2012. "Obama and his aides have used an arsenal of techniques — personal ridicule, suggestions of ethical misdeeds, and aspersions against Romney's patriotism — that many voters and commentators claim to abhor, even as the tactics have regularly proved effective.... The Obama-led attacks on Romney's character have been ... both relentless and remorseless."

It was Obama who urged Latino voters to "punish our enemies and ... reward our friends," Obama who exhorted Democratic supporters that "If [Republicans] bring a knife to the fight, we bring a gun," and Obama who insisted that legislators who opposed the Affordable Care Act did so for only one reason: because their goal was "making sure that 30 million people don't have health care."

No, the polarization of American political life did not begin under Obama. He wasn't to blame for the fact that partisan antipathy had been growing since the 1990s. But Obama deserves considerable blame for never making an effort to slow or reverse that trend. It would not have required "the gifts of Lincoln or Roosevelt" to try to raise the tone of the nation's discourse. As I remarked in 2016, the gifts of Gerald Ford would have done nicely.

Prior to Obama, no chief executive in modern times was as quick to impugn his critics' motives or to demonize those who opposed him. After he left the White House, the sour spitefulness of American politics grew far worse, thanks above all to Trump's malignant influence (with an assist from Joe Biden). But the downward spiral was underway years before Trump descended that escalator in 2015. It wasn't all Obama's doing. But it was Obama who had pledged, again and again, to lead the way in restoring a measure of harmony to American politics — but never even tried.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Gout and its peculiar myths

When I woke up Thursday, my right foot was throbbing with pain, which quickly intensified to the point that I could only walk with a pronounced limp. It was an attack of gout and I knew what to expect: My foot was going to be tormenting me until medication could turn the pain around.

Five years ago, I'd have had no idea what was happening. For most of my life I knew as much about gout as I know about rugby, the history of Thailand, or Riemannian geometry, which is to say, next to nothing. I shared the popular perception that it is an affliction that mostly affects the corpulent well-to-do and is triggered by an excessively rich diet. But I had never given the subject much thought.

I once read that Benjamin Franklin suffered from gout so severe he had to be carried into Philadelphia's Independence Hall on a sedan chair during the constitutional convention in 1787. In a comic "dialogue" with his gout that he published a few years earlier, he denounced the ailment as "my enemy." When gout objected that it was nothing of the kind, Franklin replied: "I repeat it, my enemy — for you would not only torment my body to death, but ruin my good name; you reproach me as a glutton and a tippler." In response to a particularly severe spasm, Franklin moaned: "Oh! Oh! For Heaven's sake! Leave me, and I promise faithfully never more to play at chess, but to take exercise daily, and live temperately."

Writing in the late 1800s, the caustic Ambrose Bierce defined gout in "The Devil's Dictionary" as "a physician's name for the rheumatism of a rich patient." Bierce was a satirist, but his characterization pretty much summed up my view of gout.

Until I experienced it for myself.

One fine day in 2019 my ankle, which had never bothered me before, suddenly grew painful and swollen, forcing me to limp on my way home from work. The next day, the pain was so acute that I couldn't bear to put any weight on it and needed crutches to get around. I thought I must have somehow sprained an ankle but when I eventually went to a doctor, she needed only about two minutes to diagnose my condition as gout. That was how I learned that I had been inducted into what the writer Geoff Nicholson once called "that shadowy, shameful group, the 'gout community.' "

When my younger son learned of my diagnosis that evening, he was pleased to inform me that gout is a rich person's disease caused by too much unhealthy eating — pretty much what I had always believed. Now I knew better. Gout is caused by high levels of uric acid in the blood, which in some people has a tendency to crystallize and collect in the body's joints, especially those in the feet. About 65 percent of the time, genetics are to blame for that tendency. Gout is also known to occur more frequently in people who drink a lot of beer, sugary beverages, or alcoholic spirits, or whose diet is rich in shellfish, anchovies, or liver and other organ meats. As it happens, my diet contains none of those, except for a whiskey once or twice a week. So I assume that my propensity for uric acid crystallization was most likely bequeathed to me by my parents. Considering how many other things of value I received from them, I can hardly complain.

There is no cure for gout but it can be treated with medication. I take a daily medication, allopurinol, which keeps it at bay most of the time. When gout does flare up, another medication, colchicine, can gradually get the pain under control. My latest attack subsided within 48 hours.

Gout has inspired some truly peculiar myths. For centuries it was thought to be more of a cure than an affliction — a protection generated by the body as a defense against much worse, possibly lethal ailments. Jonathan Swift expresses that idea in "Bec's Birthday," a poem he wrote in 1726:

As, if the gout should seize the head,

Doctors pronounce the patient dead;

But, if they can, by all their arts,

Eject it to th'extremest parts,

They give the sick man joy, and praise

The gout that will prolong his days.

Horace Walpole, the 18th-century English politician and man of letters, was of the same view. Gout "prevents other illness and prolongs life," he wrote to one correspondent. "Could I cure the gout, should not I have a fever, a palsy, or an apoplexy?" Though he suffered from painful flares all his life, he insisted that gout was "a remedy and not a disease, and being so no wonder there is no medicine for it, nor do I desire to be fully cured of a remedy." Those who did seek cures or treatments for their pain, meanwhile, were said to have only themselves to blame for what might ensue. When Samuel Johnson, another gout sufferer, tried soaking his feet in cold water, "his friend Hester Thrale was aghast," declaring, as the medical historian Roy Porter recounted in 1992, that "he will drive the gout away ... when it comes, and it must go somewhere."

Johnson's death, four years later, confirmed her woeful prognostications. "I am persuaded," she wrote, "[that] Dr. Johnson died of repelled gout. You may remember the trick his played at Sunninghill [of] putting his feet in cold water. He never was well after."

Even more preposterous was the belief that gout was a disease of the talented and the esteemed. Porter quotes Sydney Smith, the writer, cleric, and founder of the influential Edinburgh Review: "Gout loves ancestors and genealogy. It needs five or six generations of gentlemen or noblemen to give it its full vigor."

In Charles Dickens's novel "Bleak House," Sir Leicester Dedlock undergoes agonizing attacks of gout in both legs, but he regards it as evidence of his patrician lineage. He is proud that "all the Dedlocks, in the direct male line, through a course of time during and beyond which the memory of man goeth not to the contrary, have had the gout," declares the narrator. He continues:

It has come down through the illustrious line like the plate, or the pictures, or the place in Lincolnshire. It is among their dignities. Sir Leicester is perhaps not wholly without an impression, though he has never resolved it into words, that the angel of death in the discharge of his necessary duties may observe to the shades of the aristocracy, "My lords and gentlemen, I have the honor to present to you another Dedlock certified to have arrived per the family gout."

Hence Sir Leicester yields up his family legs to the family disorder as if he held his name and fortune on that feudal tenure. He feels that for a Dedlock to be laid upon his back and spasmodically twitched and stabbed in his extremities is a liberty taken somewhere, but he thinks, "We have all yielded to this; it belongs to us; it has for some hundreds of years been understood that we are not to make the vaults in the park interesting on more ignoble terms; and I submit myself to the compromise."

Well, you can take it from me and the more than 12 million other Americans who have a history of gout that there is nothing "illustrious" about this malady. It is just one of the innumerable painful ways in which something in the human body can go wrong. Happily, modern medicine can set it right. Praise be.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "A 'beached whale' for South Boston," Nov 1, 1999:

Boston has never been a bigger-is-better kind of city. People don't come here so they can gawk at massive buildings. For that they can go to New York or Chicago. If they yearn to share the sidewalks with 80,000 visiting chiropractors or the entire membership of the International Congress of Used Car Dealers, there is always Orlando or Anaheim. What gives Boston its charm and appeal is the very opposite of enormousness — it is the human scale of its neighborhoods and the intimacy of its historic districts. When did we decide those weren't enough?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Hill House itself, not sane, stood against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, its walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone." — Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe.

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read something different? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.