WHEN JAPAN surrendered to the United States in 1945, Seiji Ozawa liked to recall, his father's reaction was: "Now, let's play baseball!" During World War II, baseball had been scorned by pro-government forces as an enemy import, and in 1944 the games were halted. But with the American victory, yakyū — Japanese for baseball — returned to the ballparks. So did 10-year-old Seiji, wearing homemade gloves sewn by his mother.

Ozawa's passion for the sport never faded. The musician destined to lead the Boston Symphony Orchestra for a record 29 years saw his first major league baseball game at Fenway Park in 1960. For the next 64 years, he was an avid Red Sox fan. When Boston went to the World Series in 2013, Ozawa — by then retired and struggling with cancer — insisted on flying to Boston for what would turn out to be the team's eighth world championship. He also conducted the Boston side of the pre-Series "brass-off" between members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. In the delightful YouTube video, he exclaims "Bring it on!" while wearing a jersey bearing David Ortiz's No. 34.

Ozawa's passion for American baseball was a subset of his affection for the United States. He was born in Japanese-occupied Manchuria in 1935, but his family returned to Japan a few years later and he lived through the cataclysmic Japanese defeat in World War II. Far from resenting the American victors, however, he idolized them.

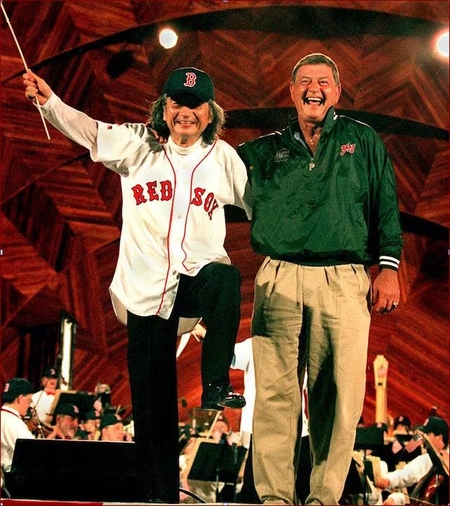

An exuberant Seiji Ozawa joined the legendary Red Sox left-fielder Carl Yastrzemski on the Esplanade for Boston's Fourth of July festivities in 1999. |

"We had to hide our happiness because the emperor had declared this a national tragedy," Ozawa told the Globe in 1994. "But in our homes we were happy because we knew that now we would be able to live. And when the American soldiers came, everything changed." His teachers had told him and his classmates that "the Americans were animals and murderers. [Yet] here they came in their Jeeps, singing and playing guitars and giving chewing gum to all the children. I never had Juicy Fruit before. In one day, everyone was happy on the street."

What a madeleine dipped in tea was for Marcel Proust's narrator, Juicy Fruit would be for Ozawa. "I never go past the chewing gum displays in the supermarket and smell it without thinking about that day," he said in 1994.

Ozawa got his first glimpse of an American when a US Army Air Corps pilot flew low over his hometown of Tachikawa. Ozawa and some friends, swimming naked in the river, quickly tried to hide when the air-raid siren sounded. "I could actually see the face of the pilot who was coming at me — it was the very first American face I ever saw," he later reminisced. "I was only 7 and he was maybe only 10 or 12 years older.... I wonder where he is now, and what his life is like. Now I feel like an American myself."

Ozawa, who passed away in Tokyo on Feb. 6 at 88, was "Japanese through and through," as a Washington Post profile put it. But he was also, like so many immigrants, filled with appreciation and affection for his adopted homeland.

At Boston's Symphony Hall on Oct. 3, 2001, just a few weeks after the horror of 9/11, Ozawa began his farewell season as conductor of the BSO.

"Ozawa made a signal," the Globe reported the next day, "and Elijah Magee of Ladder Company 15 of the Boston Fire Department — the Symphony Hall fire station — solemnly bore the spotlit flag up the center aisle to the front as the audience again rose to its feet and applauded. The brass of the BSO nobly intoned the opening of 'America the Beautiful' and soloists, members of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, and the audience joined in singing two verses as tears streamed down the faces of many." Among the eyes seen to well with tears that evening were those of Maestro Ozawa, a great musician and a great American.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

That old radio magic

I have been leafing through "The Mathematical Radio," a new book by the physicist and electrical engineer Paul J. Nahin. An emeritus professor at the University of New Hampshire, Nahin is the author of numerous books on math, science, engineering, and science fiction. Much of his latest volume, on radio technology and the mathematics that make it work, is too advanced for me — I never got beyond rudimentary high school trigonometry — but his introduction got my attention with an arresting claim about the significance of radio in world history.

"Radio is perhaps the single most important electronic invention of all, surpassing even the computer in its societal impact," Nahin writes. Not even the telephone or television, he argues, transformed the world the way radio did. "Even if we drop the 'electronic' qualifier, only the automobile can compete with radio in terms of its effect on changing the very structure of society."

The astonishing speed with which radios became a mainstay of American life suggests how irresistible the new technology was. In 1923, with radio in its infancy, just 1 percent of US households had a radio. Within eight years, a majority of American families owned at least one. By 1937, just 14 years after first appearing on the market, radios could be found in 75 percent of American homes. By way of comparison, consider these numbers from Robert Putnam's classic "Bowling Alone," it took 23 years before refrigerators had spread to 75 percent of homes, 48 years for vacuum cleaners to reach that level of penetration, 52 years for automobiles, and 67 years for telephones.

Once Americans got a taste of what radio offered, nothing could stop its spread.

"During the Great Depression the growth of ... both the automobile and the telephone in American households faltered," observes Nahin, "while the spread of radio sets continued unabated even during those disastrous years." Partly that was because so little infrastructure was required to support the use of radios. To sell more cars there had to be more service stations and highways; before more homes could get telephone service, miles of poles and wires had to be erected. But "the only thing between a radio station and a radio receiver is air."

The author quotes R.V. Jones, a British scientific intelligence agent and confidant of Winston Churchill during the Second World War who was a pioneer of what today would be called electronic warfare.

"There has never been anything comparable in any other period of history to the impact of radio on the ordinary individual in the 1920s," Jones remarked. "It was the product of some of the most imaginative developments that have ever occurred in physics and it was as near magic as anyone could conceive.... [W]ith a few mainly home-made components simply connected together one could conjure speech and music from the air."

A Philco 90 "cathedral"-style radio from 1931. |

Jones used the word magic advisedly. In a famous aphorism, the science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke once declared: "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." Try to imagine the astonishment — or fear — with which anyone alive before, say, 1890 would have reacted to the sight and sound of a working radio. A stand-alone box from which real human voices and music emerge? "In the Middle Ages," Nahin writes, "such a gadget would have gotten its owner burned at the stake" for consorting with the devil.

Even sophisticated modern intellectuals found radio hard to make sense of in its early years. Chief Justice William Howard Taft, who headed the Supreme Court from 1921 through 1930, admitted to a friend that he had "always dodged this radio question." He shied away from litigation involving the new technology. "I have refused to grant writs and have told the other justices that I hope to avoid passing on this subject as long as possible," Taft said. When asked why, he admitted that radio spooked him: "Interpreting the law on this subject is something like trying to interpret the law of the occult. It seems like dealing with something supernatural."

To be sure, tens of millions of not-so-old people today — Baby Boomers and Gen Xers — have lived through the appearance of extraordinary new technologies: personal computers, email and the internet, cellular telephones. But all those tech wonders were unveiled in a world in which people were already used to the idea of communicating in real time with unseen individuals far away through devices not attached to wires or cables. A century ago, that concept was unheard-of. Nothing afterward was the same.

My mother, who was born in 1932, was part of the first generation to experience mass radio communication. Radio for her was no mere background entertainment; it was intensely vivid — intensely present. She told me that when a favorite show came on, she and her friends wouldn't just listen. They would gather around the radio set and watch, reacting to what they were hearing as if it were taking place in front them. She and several other girls, smitten with the young Frank Sinatra, faithfully tuned in to "Your Hit Parade" and other shows on which he appeared. At the first sound of his voice, my mother remembered, she and the other girls would scream with excitement and fall off their chairs!

For my wife, growing up decades later in a very rural section of northern New York, hard by the Canadian border and far from big-city life and entertainments, radio was a crucial lifeline. In bed late at night, she could tune in Boston's WBZ on a little transistor radio and keep up with her first sports passion: Bruins hockey. To this day, she has never attended a Bruins game in person. But radio made it possible for her to absorb hundreds of them as a hockey-hooked teenager far from Boston.

There are other, more urgent ways in which radio has been a lifeline. In March 1990, just a few months after the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe, I had the opportunity to travel through Hungary, Romania, and the still-united Czechoslovakia. In Bucharest, one family showed me the hidden shelf in a closet where they kept the short-wave radio on which they tuned into broadcasts by Radio Free Europe — the American broadcast service that beamed accurate news to listeners behind the Iron Curtain, as well as programs on religion, science, Western music, and literature banned under the communists. Those radio broadcasts helped keep democratic hopes alive during the iciest stretches of the Cold War. They were just one more example of radio's world-changing impact.

Today, a century after radio was born, what could be more prosaic? No one looks at a radio in 2024 and thinks: "Magic!" But its arrival was indeed magical. Whether we realize it or not, we all still live within its spell.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

Not your typical column

This month marks a career milestone: It was 30 years ago that I joined The Boston Globe as an op-ed columnist.

Writing two columns weekly adds up: My byline has appeared on roughly 2,600 opinion pieces since February 1994, when I introduced myself to readers with a column that began: "So what's a nice conservative like me doing in a newspaper like this?" And that doesn't include the many additional words I have written since launching Arguable seven years ago.

When I made my debut as the Opinion section's most junior columnist, my colleagues included some of the Globe's most storied journalists — among them, David Nyhan, Tom Oliphant, Robert L. Turner, and Susan Trausch. On the morning my first column was published, I got an excited call from a friend who worked at the Harvard Divinity School. "I can't believe it!" he exclaimed. "You're on the same page as Ellen Goodman!"

In the nature of things, most of what I write necessarily concerns itself with the news of the day: politics and policy, foreign affairs, war and peace, the economy, crime, and cultural controversies. But every now and then I've devoted a column to some idiosyncratic topic that no one was expecting and that I've never written about since. Since 2022, I have reprinted in Arguable each week, under the heading "What I Wrote Then," a snippet from a column that ran 25 years earlier that week. (I got the idea from the old International Herald Tribune, which used to do something similar with its news archive.) Most weeks I'll keep doing so — many of you have told me you like the weekly glance back at what was in the air a quarter-century ago. But for a bit of a change-up, I propose to resurrect from the archives each month one of those off-the-beaten-path columns — just for the quirky fun of it.

With Valentine's Day almost upon us, here's the first: a column I wrote in 1995 on the unlikely subject of love.

"What love is — and isn't," Feb. 14, 1995:

WHAT IS this thing called love? Perhaps only a fool rushes in where philosophers and artists have already trod. But today is the feast of Saint Valentine, and on this day even newspaper scribblers may speculate on love.

Never having to say you're sorry is not what love is. Love — true love — isn't being wild again, beguiled again, a simpering, whimpering child again. It's not that old black magic. It's not growing accustomed to her face — or to his.

Maybe love, like a shiver, cannot really be explained, only experienced. So suggests the most romantic love poem I know. In "A Valediction: forbidding mourning," John Donne urges his wife — from whom he is about to be separated — not to grieve over his absence. Donne was no angel. Described in his youth as "a great visitor of Ladies," he wrote some of the raciest poetry of his day. Yet only for shallow people, he tells his adored Ann, does love depend on the physical senses. True love isn't so easily comprehended. It is stronger; finer. And distance only increases it:

But we, by a love so much refined

That our selves know not what it is,

Inter-assured of the mind

Care less eyes, lips, and hands to miss.Our two souls, therefore, which are one

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion

Like gold to airy thinness beat.They say that falling in love is wonderful, wonderful — but to judge from our national divorce rate, the real miracle is staying in love. No-fault divorce laws may be part of the explanation for the collapse of so many marriages today — like buying something from L.L. Bean, it's easy to undo the transaction if you change your mind — but part of it is also a great national confusion between passion and love.

"If we had a problem," wrote O.J. Simpson, who once pleaded no contest to beating his wife, "it's because I loved her so much." Is that what that was? Love?

Anti-love is more like it. And it's nothing new. Fifty years before Nicole Simpson was found with her head nearly sawed off, the Mills Brothers' "You Always Hurt the One You Love" went gold. It was, and is, a marvelously hummable, danceable song — but the warped sentiment it expresses is a lot closer to O.J. Simpson than to John Donne.

You always take the sweetest rose

And crush it 'til the petals fall.. . . So if I broke your heart last night

It's because I love you most of all.I suppose I know about as much of love, or as little, as any other thirtysomething American single. But I do know what love looks like. I was raised by two parents who derive deep satisfaction from their marriage to each other. During my growing-up years, it occurs to me, I had a ringside seat at a true-love story. Of the many gifts my parents gave me, that has to rank among the most valuable.

"Doesn't it drive you crazy when Mom does that?" I once asked my father, when my mother was doing something I found maddening.

"I'm sure I do things that drive your mother crazy," he answered, not quite answering. "If you love somebody, you learn to accept things you don't like." At 17, I had no real idea what he was talking about. But then, at 17, I'd never been in love, and hadn't yet found out that the quest for perfection is the best way not to find love.

So many centuries after Hero and Leander, after Jacob and Rachel, after Romeo and Juliet, is there anything new to be learned about love? Might as well ask if there's anything new to be learned about walking. Some conundrums we just have to puzzle out for ourselves.

So what is this thing called love? I'll venture a definition: Love is when another person's happiness is as important to you as your own.

Your ardor for someone isn't proof of love, though that can be an element of it. You may go to great lengths to be with her, you may burn for her, be dazzled by her, want her all to yourself forever and always. That doesn't mean you love her.

But if you can't be happy unless she is, if only her joy makes you truly joyful — ah, that's love. And on this Valentine's Day, I can wish you no better than this: that love is either in your heart, or on its way.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"But the darkness has passed

And it's daylight at last

And the night has been long

Ditto, ditto my song

And thank goodness they're both of them over!" — W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, "The Nightmare Song" from Iolanthe (1882)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.